Moving back from New York City to Central Pennsylvania has been like the Five Stages of Grief, if only the last stage were eating hot soup with a hard-boiled egg in it on a 90 ̊F day in August, which is what I’ve been doing. In other words, I’m becoming a native again.

Moving back to a place as particular as my hometown of York, Pennsylvania appealed after rootless years in a coastal city. From our rich colonial history to our high concentration of snack manufacturers and the pack of wild turkeys that patrols the bike path along the old railroad, York may not be an elite metropolis, but it’s no anonymous suburban wasteland, either. We owe some of that specificity to the Pennsylvania Dutch.

The Pennsylvania Dutch were not in fact from Holland, but from the German Palatinate (‘Deutsch’ became ‘Dutch’). They began immigrating in the late 1600s to the colony best known for religious freedom. The Amish sought asylum in this region, and Lutherans, Mennonites and Moravians came too. Their collective culture has proved remarkably resilient. Some folks still speak Pennsylvania Dutch, a centuries-old dialect that is neither written down nor intelligible to Standard German speakers. Their English isn’t always intelligible to Standard English speakers, either, but they’ve managed to pass on their culinary traditions.

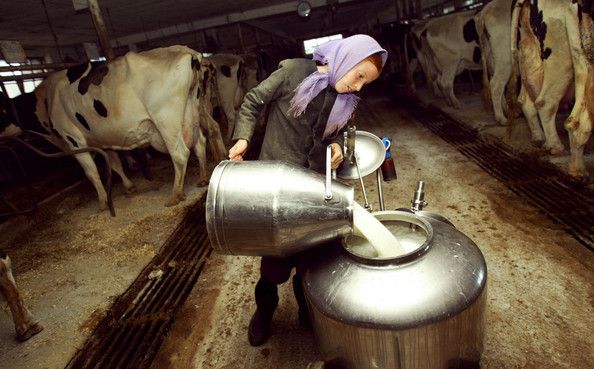

Pennsylvania Dutch food is the product of farmhouse economy and harsh winters: heavy, starchy and fermented — potatoes, corn, cabbage, egg noodles. My aunt once attended a firehall wedding where the entire meal, hors d’oeuvres to dessert, was beige. But you have to admire the resourcefulness. If you butcher an animal, you’ll use every single part: pickle the tongue, snout and feet; stuff the stomach (‘hog maw’); grind up whatever’s left into a congealed breakfast loaf (‘scrapple’). Waste not, want not.

I’m Irish Catholic myself, descended from a people not known for thrift, industry or culinary subtlety. But if you grow up around here, you get used to the sight of red beet eggs in the deli window, vinegared macaroni casserole at the church picnic, and adults preferring disgusting foods to tasty ones. These usually fall under the ominous term ‘salad’. The Pennsylvania Dutch stipulate 14 side dishes — seven sweet and seven sour — on the table at any celebratory meal.

Being a local once more, I decided to drop by the farmer’s market and pick out a few traditional dishes. Had the change in my zip code changed my palate? Myers’s Salads has been selling side dishes in since 1921. The woman running the stand wore a Mennonite hairnet. When I asked if she was Pennsylvania Dutch, she replied, ‘I guess I was raised that way.’ Her recommendations for traditional foods were a red beet egg (‘Just one?’), chicken corn soup, pepper slaw, a dish of pickles and cauliflower in mustard sauce, and maybe a spoonful of the ham salad.

The dominant flavor profile in my bounty of half-pint plastic containers was the bread-and-butter pickle: tangy and cloying. Red beet eggs are hard boiled and pickled in sugar and beet juice; they look like a Halloween decoration and taste like shoe insoles in sweet-and-sour sauce. I have a sentimental attachment to chicken corn soup, having spent many childhood summer afternoons musing at the old-timers in lawn chairs at local baseball games, eating soup from a cauldron in the snack bar. I couldn’t possibly have imagined that their Styrofoam bowls contained slivers of hard-boiled egg: a sly nutritional boost at the price of an unappealing smell and texture, like protein powder for pre-moderns.

In my final attempt to grow into Pennsylvania Dutch food, I borrowed a family friend’s ancestral Shoo-Fly Pie recipe. Shoo-Fly Pie, a molasses based breakfast food or dessert, is the queen of Pennsylvania Dutch cuisine. It’s widely available in diners across Central Pennsylvania, and has even been appropriated by a billboard I can see from my window, which boldly attempts to sell fashion sneakers to Mennonites with the tagline Shoe Fly. Made with limited eggs and dairy, and without the delicate, seasonal, perishable fruits of most other pies, Shoo-Fly Pie combines the hallmarks of this style of cooking: it’s cheap, hearty, fortifying and a little too sweet. Still, it’s good with black coffee. If you visit me in my new home I’ll gladly make it for you — with or without a side of red beet eggs.

Shoo-Fly Pie

Ingredients

For the crumb: 3⁄4 cup flour; 1⁄2 cup brown sugar; 1⁄4 teaspoon salt; 1⁄2 teaspoon cinnamon; 1⁄4 teaspoon ground ginger; 2 tablespoons shortening

For the liquid: 1⁄2 cup light molasses; 3⁄4 cup hot water; 1 egg; 1 teaspoon baking soda

Method

1. Mix crumbs and liquid in separate containers

2. Pour the liquids into an unbaked pie shell

3. Top with crumbs

4. Bake at 375 ̊ for 45 minutes

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2021 US edition.