How better to lift a torch against late-winter gloom than by conjuring an evening from a time when our country was still a confident going concern, when its culture and ideas bestrode the free world? What with our plague-driven mania for virtual living, it’s hard to get anyone to come to dinner these days. And since she died in 1969, our virtual guest of honor won’t be coming either. But from an era full of entertainment giants, we pick one, the star of stars: Miss Judy Garland.

If only in our minds, we invite Judy to cocktails and dinner and then, just maybe if we get lucky, to linger late into the evening around the piano and sing a few of the old songs. This is not a formal affair, just two couples on a Friday evening after work. We stir, cook and generally enjoy ourselves in the style of six or seven decades ago. We do not have in mind some ersatz retro-nostalgia event. While we all happen to be past the half-century mark, this territory is not by any means off-limits to the young, though it calls for a smidgen of historical imagination. Our program is in two parts.

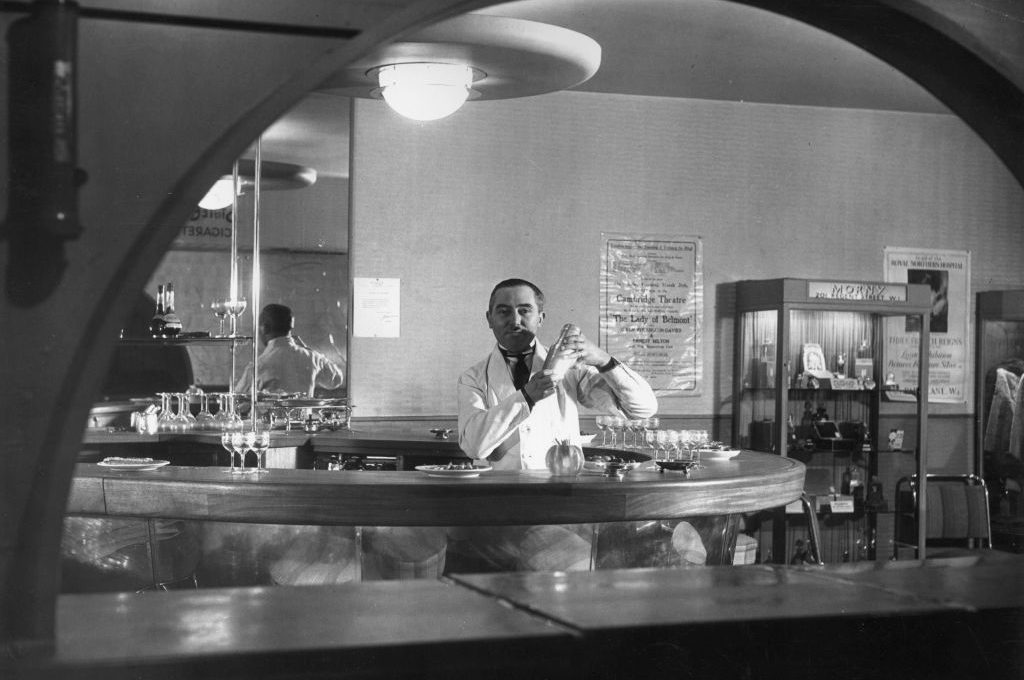

Dinner. Right preliminaries set the right mood. To begin the evening, we put on the turntable the two-platter album Judy at Carnegie Hall, recorded live 60 years ago this year, which nicely covers the two hours or so till dinner. Faithful to the fact that back then Americans downed more grain than grape, we open the bar with ‘mixed drinks’. And as the evening will belong and no one is driving home, we measure for more than one round. (Caveat: ‘choice’ is not in the right spirit. Everyone gets what the host is pouring and is thankful.) For his part, the host must not get inventive but let tradition rule. He does not, therefore, attempt that greatest of the classics, the Old Fashioned, which must be assembled painstakingly, one at a time. Something suited to a pitcher or shaker is called for. Manhattans are acceptable. Martinis are best.

Here memory reverts to another LP from that era, though it features a lesser talent by far: Jackie Gleason. In addition to his Saturday night television show The Honeymooners, where he shared the bill with Art Carney and Audrey Meadows, Gleason had his own orchestra, specializing in swoony orchestrations of big-time hits. My parents collected several of these early Capitol Hi-Fi LPs, including, naturally, one called Music, Martinis and Memories. Alluring yet tasteful jacket art no doubt helped sales: a svelte Fifties lovely in a strapless sequined cocktail dress accented with mink pensively holds aloft her martini, with the piano player hard at work in the background. Hers or ours, martinis may be shaken or stirred, but they must be made with gin and minimal vermouth. To accompany, simple hors d’oeuvres of smoked salmon or a spot of caviar, plus a couple of nice cheeses, will suffice. (At this point a further caveat: it is important to get the balance right in anticipation of what’s to come. Better to over do on the martinis than on the hors d’oeuvres, however tempting the little morsels may be. Do not, a sour mothers rightly admonished, spoil your appetite.)

Most Americans did not think much in terms of ‘courses’ back then (the first truly multi-course menu I saw was on a liner to Europe in 1962), though there was often an at-the-table ‘starter’ or ‘appetizer’ beyond the passed hors d’oeuvres. For our Judy dinner, we go with that staple of starters, c. 1955, the shrimp cocktail. It comes in many variations, plain to fancy. Plain will do, requiring only ice-cold Gulf shrimp, horseradishy red cocktail sauce, lemon and a stemmed glass for serving, as few of us any longer have in our kit those marvelous glass-lined silver-plate affairs with the ice underneath, once common in railroad dining cars and hotel restaurants.

Into the early 1960s, any ‘fancy’ restaurant in America, and some not so fancy, would have offered tonight’s menu as ‘Best of the House’. In many ways, it still is. It survives today largely in high-to-overpriced steak-houses where, in the age of olive oil and kale, it amounts to a counter-cultural statement. Back then, it was commoner currency, and not class-specific. Steak, necessarily, was its centerpiece: always cornfed western sirloin, never effete grass-fed filet. This is because steak was richly symbolic to Americans then: America’s farmers and ranchers raised beef, and steak was the best beef there was. Whenever you were even a little bit in the money, a steak dinner was how you celebrated.

To repeat: sirloin only, never filet; strip is fine though bone-in, which is harder to find, is better. Thicker is better too; this is not a Frenchy pan-seared piece of meat. Cook the meat to your guests’ preferred doneness, either outside on the coals or inside under the broiler. Steak sauce — A-1, HP, Heinz 57, Lea & Perrins — is not yet thought gauche. Two accompaniments, and only two, are essential. For the starch, a generous but not ‘jumbo’ baked potato, which can be baked naked or rolled first in oil and salt to crisp the skin. Serve with butter, salt and pepper.

Second is that wedge salad. As with shrimp cocktail, there are many variations, but do not fuss. Adhere to simple ingredients: chilled iceberg lettuce, quartered, crumbled bacon, chopped tomato plus the dressing. One excellent iteration combines sour cream, mayonnaise and buttermilk with red wine vinegar, diced red onion, garlic and blue cheese, with (this is important) more blue cheese reserved for sprinkling on top. Finish with black pepper. Obviously, the quality of the ingredients matters, but so does the quantity: when dressing, dress generously. A green vegetable may be served as well but isn’t required. Pretty much anything green works: asparagus, string beans, even peas, buttered, of course.

That’s it, except for dessert. Again, keep it classic, as in sour cream cheesecake anchored in a butter-graham-cracker-and-walnut crust. This version (served straight up and undecorated, no fruits or coulis, thank you very much) comes from that cookbook at which Julia Child turned up her nose but which, for decades, my mother kept on the shelf ‘right beside Julia’ and which, well-stained and annotated, now sits on mine: Irma Rombauer’s classic compendium,The Joy of Cooking, in print since it first appeared in 1931.

Finally, a word about the wine. Depending on your constitution, you may wish to stick with martini(s) right through dinner. This is fine. If not, pretty much any decently dry, red, heavy grape will do. A version of this menu as offered on the Super Chief, the Chicago-to-Los Angeles ‘Train of the Stars’ frequented by Judy and other Hollywood celebs in the Forties, Fifties and Sixties, featured Champagne. But if you preferred, the steward would happily pour a simple but solid ‘California Burgundy’. All for $6.50, tip not included.

Postprandial. Content here is more negotiable than with dinner. We suggest two possibilities that work well, in concert or singly. If there is a piano— preferably a small grand on which you and your guests can lean — and if someone plays, trot out some of the old Arlen, Gershwin, Berlin, Rodgers torch songs that Judy made her own. Your efforts, however piffling, will be a salute to past excellence and make for a worthy ritual. Singing, even late-at-night not-very-good singing, heightens camaraderie in the moment and sometimes surprises. Who knows what velvet tones lurk amongst your relaxed and mellow guests? You will, after all, be treading holy ground, through the pages of the Great American Songbook. So what if you can’t manage those fabulous fifths quite like Judy did? You can sing, speak and hear some of the finest lyrics ever written:

‘As he started to leave

I took hold of his sleeve with my hand

And as if it were planned

He stayed on with me

And it was grand just to stand

With his hand holding mine

To the end of the line’

If your crew will not rise to this challenge (or if they do and consequently need to rest a while), then repair to a room with a good screen and speakers and settle back for one of the great shows. Some strong coffee may be advisable at this point and, for the hearty, a nightcap. For Me and My Gal, Girl Crazy, Babes on Broadway, Meet Me in St Louis, The Harvey Girls, Summer Stock or, at the apex, A Star is Born — any of them will do. By this time, you will have reached the wee small hours of the morning. Before dropping into bed, drop the needle one last time on the Carnegie Hall recording, at the spot of that unforgettable unscripted interjection of Judy’s very near the end of the show, when the audience just won’t sit down. ‘I know, I know,’ purrs the star, mic in one hand, reaching over the foot-lights with the other. ‘I’ll sing ’em all and we’ll stay all night’.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2021 US edition.