The world of 2023, which scarcely speaks for the intelligence, the competence, or the success of the human race, does revive the age-old question of whether the individual is wiser than the species. One answer, stated in its simplest form, is the old saw that two heads are better than one. But is that true? And if so, are three heads better than two, und so weiter? Where do we come to the end of this?

The key to the conundrum relates to government. Does oligarchy provide wiser rule than monarchy, aristocracy than oligarchy, and democracy than aristocracy? Consider the history of Britain and British government over the past centuries. Has democracy, in progressively greater measure, improved the management of British affairs since the eighteenth century? Has the civil service heightened the competence and efficiency of the British state since it replaced second sons with professionally trained officials drawn from the middle classes?

Look to the other side of the Atlantic: did the reforms of the Progressive era in the United States accomplish what the Progressive Party insisted they would? The United States and Great Britain are the two most democratic countries in world history, yet the present Tory government, now led by Rishi Sunak, is one of the most inept — actually useless — in recent British history, as the Biden administration is the most incompetent, ridiculous, corrupt and dangerous the Republic has ever seen.

It may be that the geographical extent of a country, the size of its population, and its demographic makeup ultimately determine the wisdom of its governors. Britain throughout most of her history has enjoyed well-run government; the United States, for all her material success, has not since the end of the Jeffersonian period, which Jefferson and John Adams recognized was also the end of the Founding era. Their own replacement (as Jefferson wrote to Adams in their old age) was by “new” as well as younger men “who know us not.” Neither country has been as well managed in a formal way as Switzerland, likewise a democracy, but a tiny country in terms of territory and population alike, vastly smaller than the US and much smaller than the UK.

It seems plausible that a small, or relatively small, democracy is more intelligent and more wisely ruled than a modern mass one like America. The character of mass democracy is formed by the mass democratic mind, which is really the absence of mind. The mass mind was beginning to evolve from the popular one in the American republic relatively early in its history, as Tocqueville recognized upon his arrival in 1830. It has been remaking Great Britain since before World War Two (Evelyn Waugh deplored “the age of the common man”), but in Britain it still has a deeper cultural stamp and a more distinct character than in America. The Swiss Republic, by comparison, is more homogeneous and culturally focused than either country, and consequently more localized and democratic in the representative sense.

It seems that a well-preserved national culture and character embodied by a population of a politically manageable size is more important than the formal intelligence of its political leaders in maintaining wise government and a healthy society. A successful country’s history and its culture are the “two heads put together” that make it politically intelligent and competent, nationally strong and materially prosperous. This theory agrees with Aristotle’s understanding of the connection between a wise polity and the ideal size of a state, and later that of the philosophes — notably Rousseau — of the European Enlightenment, who adopted it in their own theoretical speculations.

If it seems only common sense that two heads together are more likely to reason rightly than one, it is not illogical to imagine that the general rule may yield progressively diminishing returns with the addition of more heads, depending on their number, as the principle of political representation recognizes. This is why houses of popular representation everywhere are limited to a specified number of representatives, quite apart from the practical difficulties relating to seating accommodation and management.

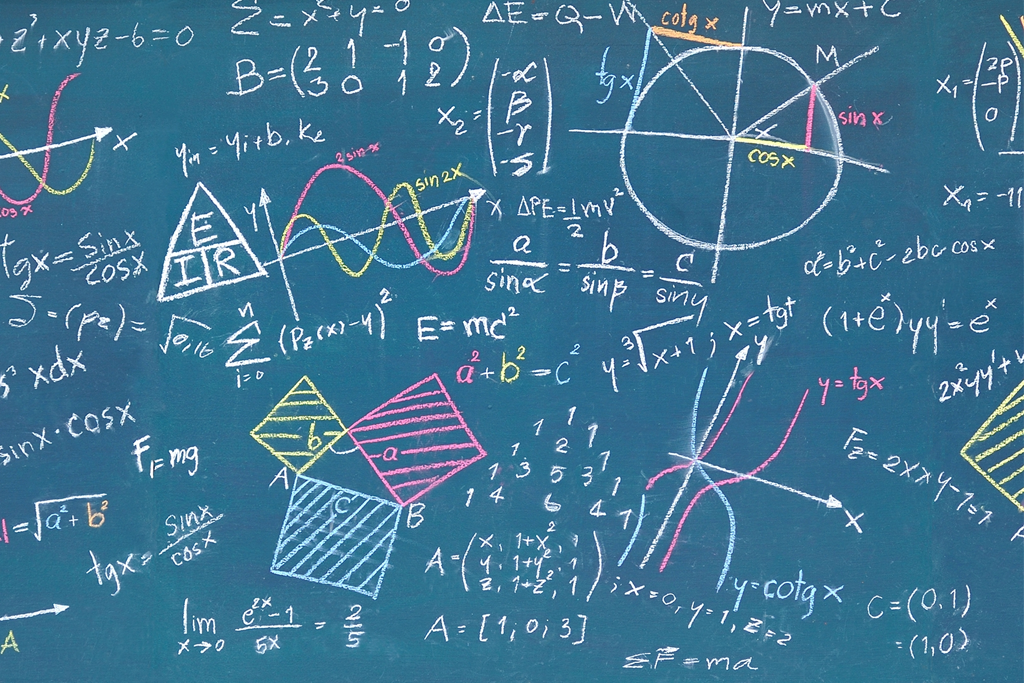

In a legislature consisting of thousands, true debate and intelligent deliberation would be impossible, and sensible decisions a matter of chance. Thus, in place of 5,000 legislators, democratic governments have 50,000,000 citizens who vote on policies proposed by their 500 representatives. It is possible that this law of diminished returns applies also in the case of population, where the proportion of highly intelligent people to those of average or low intelligence should not be expected to remain stable in a mass society with an expanding proletariat produced by the lowering of standards and values, in education and culture especially, and mass immigration.

Plato estimated 5,000 citizens — or 40,000 inhabitants, including their families, servants, slaves and foreigners — to be the ideal population of a state whose aim was to attain a high level of culture, including, of course, political culture. Rousseau took as the model for his republic the city of Geneva, which in his time numbered 25,000 people. In 2020 the population of the United States was 329.5 million people, among whom 154.6 million “heads” voted their choice in that year’s presidential election. Neither Plato nor Rousseau would have been surprised, or shocked, by the results.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2023 World edition.