Spain took on Brazil today in the final of the men’s Olympic soccer tournament. Not interested? Well, if so, you’re probably not alone — Olympic soccer has a popularity problem. For decades it has suffered from unfavorable comparisons with the big Fifa and Uefa behemoths to the extent that many see the whole thing as a bit of a waste of time. I disagree, and I so I tuned in.

For one thing, to dismiss the tournament as an irrelevance is historically ignorant. Olympic soccer (and excuse my appalling sexism but I’m confining myself to the men’s game here) predates the World Cup by 30 years and for a couple of decades was the de facto world championship, playing a valuable role in building the foundations of the international game. It has an important place in the game’s great narrative.

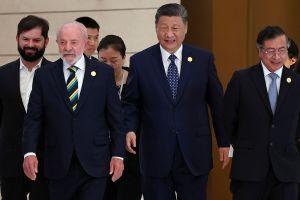

It is also a rather Eurocentric viewpoint. Brazil fixated on the Olympics for years until they finally won it at home in 2016, with a certain Neymar starring. They retained their gold earlier today, beating Spain 2-1. Lionel Messi won a gold medal for Argentina in 2008 and didn’t seem particularly embarrassed about it. Nigeria, with a host of future stars, won in 1996, as did Cameroon in 2000. And Japan’s greatest ever game, the one everyone talks about, came not in the World Cup, but in the Olympics, in 1996 when they beat Brazil — the so-called ‘The Miracle of Miami’.

It is true, though, that most of Europe’s star players avoid Olympic soccer like the plague, treating it like wearing Old Navy instead of Gucci, or driving a Buick instead of a Ferrari — beneath them, and a threat to their status and market value. Some European nations, such as Belgium and Holland, snub it all together (as have Team GB since the very early years — save for an underwhelming cameo in 2012).

But sweet are the uses of adversity: some of the drawbacks of Olympic soccer actually add to its charm. Partly, as a result of the reluctance of the big names to take part, the men’s tournament brought in an age limit (under-23 with three overage players allowed). This at least gives us something different to watch and a glimpse of the potential future. The players who do turn up are keen, and play a relatively clean game — on account, generally, of not having developed oversized egos or mastered the dark arts of ‘professionalism’. And some show tremendous promise.

This time around we have had the rare opportunity of getting a good look at Takefusa Kubo of Japan. He is hardly an unknown quantity — he’s on the books at Real Madrid — but he rarely gets a game for the Spanish superclub. He was the standout performer in the first round.

The format also benefits from the tournament’s limited aspirations. The World Cup long ago became, in the words of the immortal Brian Glanville, a ‘bloated incubus’, swollen beyond rationality to gouge as much money from sponsors and TV companies as possible, with unsatisfactory, confusing, and ever-changing tournament structures the inevitable result. Take a look at what Fifa has planned for USA 2026 if you want a glimpse of how mad it can get.

The Olympics stick to the classic 16 teams, four groups of four: quarter-finals, semi-final and final format. It doesn’t outstay its welcome and has simplicity and history on its side. This was what the World Cup used to be like, more or less, in what was arguably its golden period, the Pele years (1958-1970).

Of course, to describe Brazil as world champions for getting the gold would be laughable. The final always has the feel of a schoolboy or youth international, or even a prestige friendly — neither one thing nor the other, an adjunct to the real thing, but not quite the real thing.

But that is partly why I watched. I’ve had enough of the real thing. I largely gave the Euros a miss this year, the first international soccer tournament I haven’t watched with nerdy obsessiveness since Argentina 1978. I was tired of the hysteria, the politics, the rampant gamesmanship (also known as cheating), the bitterness and recriminations, the bombastic coverage.

I’ve seen enough of Cristiano Ronaldo (will he ever retire?) flexing his neck muscles and taking five minutes to hit a free-kick from 40 yards into row Z. I’m bored of the celebrities and the politicians hastily wrapping an England scarf around their necks and pretending to be fans — until the team loses. I also had a strong premonition, from about the quarter-finals on, that it was all getting out of hand, and would end unpleasantly — and was proved absolutely correct.

Today’s Olympic soccer final was a decent game, played in a decent spirit. It matters, but not that much. For soccer these days, that will feel like a blessed relief.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.