Somehow, I’ve lost the “Light Phone” that I bought to replace the dumb phone that I hoped would break my addiction to the iPhone. The Light Phone is the latest bit of hipster kit, designed to mimic a smartphone but without the distracting internet connection. I don’t know if it works or not because, as I say, I’ve lost it — and I’m despairing but not surprised. It’s been three-and-a-half years since I first thought I’d try to escape the iPhone’s clutches, and over that time it’s outwitted me easily and consistently.

A crop of articles have appeared recently by journalists who have made the leap and freed themselves from smartphones. I represent another, less admirable demographic. What I can offer you is not a view from the other side, but a cautionary tale.

What I hadn’t realized is the extent to which the smartphone had taken charge of my brain

I first became aware of the extent of my habit in the winter of 2018 as I cycled home from work. At each red light, I found myself fumbling for the phone in my pocket, scattering biros, and checking for updates and new messages without having made a conscious decision to do so. I noticed other cyclists doing the same, faces lit up in the evening dark. What were we looking for? What could have changed in the seven minutes between red light stops? It scared me. I found the “screentime” monitor: eight hours a day.

The next day I set about looking for a replacement phone, a “dumb” phone of the sort I used in my twenties. The iPhone was soon to be a thing of the past. I was sure of it. What I hadn’t realized is the extent to which the smartphone, with its constant internet access and array of available apps, had taken charge of my brain.

When I took that first Nokia home I was shocked by the joy I felt at the thought of escape. But quite soon my mind, servant of Apple Inc, produced the idea that I would suffer professionally without constant access to WhatsApp. WhatsApp is only available on smartphones so no, best not risk it. A year went by. WhatsApp became available on the Nokia 800 Tough, but I had another excuse ready. I said to myself that it was the smartphone keyboard I couldn’t do without. It must be available at all times for any important and lengthy thoughts.

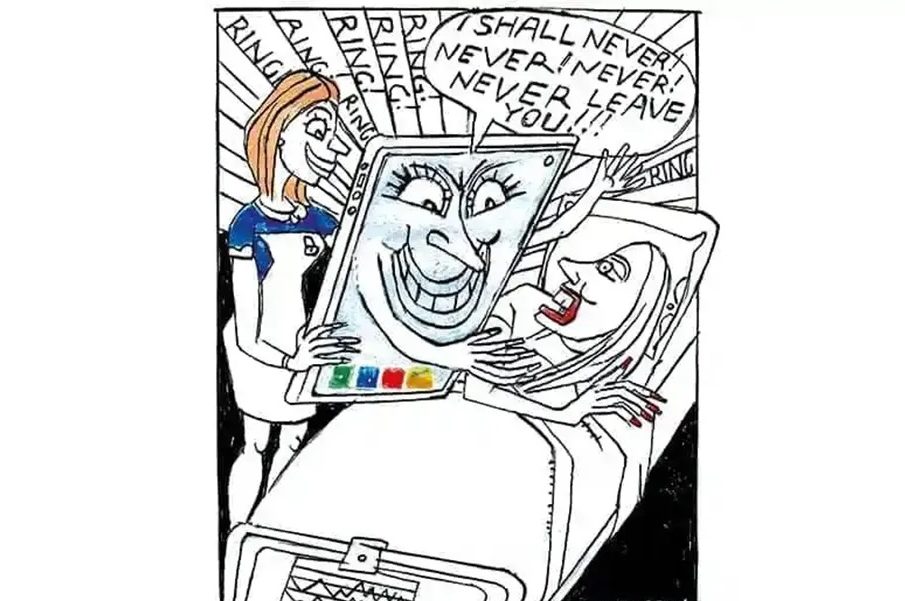

This is particularly laughable, because iPhones destroy lengthy thought. They allow only a distracted sideways crabbing from app to app in search of novelty. But as my will to leave the i-empire became weaker, so the reasons not to leave became more bogus. Why try too hard? She’s not going anywhere.

When the Light Phone arrived, with its note-taking capability, I tried to be aware of the feeble excuses not to activate it as they occurred to me. Transfer to a non-smartphone would be foolish, dangerous even, because it means a new number, which my son’s school and my mom will be bound to forget. Would I really put them in danger? This is a pathetic excuse for an excuse. Addict–thinking. Then I lost it.

I looked for the missing Light Phone in the drawer I keep for things that stab you in the fingertips. I found at the back not one but three old “dumb” phones lying side by side. Nokia, Mobiwire, Alcatel. Each one a memorial to a past failed attempt to escape.

I had forgotten them — or willed myself to forget, because my mind is not any more my own. It’s like a sort of feckless cat that’s been regularly fed by a wealthy neighbor — Apple, Amazon, Meta — and so acts, for the most part, in their interests.

But then this is how the i-trap works. It has tentacles in every cranny of your cerebrum. It offers relief from the stress it creates. So the worse you feel about being an addict, the more you ogle it. Worried about your screen time? Try a little shopping spree. Amazon one-click is always calming. On Monday, Bezos overtook Musk to become the richest man in the world again.

In the wake of the Light Phone fiasco, I’ve become wily. Like all long-term prisoners, I’ve taken my captor and I’ve studied its ways, and my next step is not another phone.

Any i-addicts in your family? Here’s the protocol. Go to settings, accessibility, display and text size; find the “color filters,” turn them on. Instantly, all the bright buttons and logos disappear. All the tools you think you need remain — photos, Instagram, WhatsApp, bank — but in shades of sludge. It’s repulsive. I’m delighted. I paw pitifully at the screen but there’s only a fraction of the usual hit. Who wants to scroll through a slug-colored Instagram? Even I can’t one-click buy what I can’t properly see.

WhatsApp too has lost its savor. When the app isn’t its trademark green, it becomes much less important to check your messages. When there’s no blue tick to signify a message has been “read,” I’m far less interested.

There’s been so much written about the brain’s craving for “newness” and the neuroscience of notifications. But how much of a smartphone’s terrible pull is contained in its hyper-real backlit colors — each bright app the product of billions worth of research?

I looked for official research but found only one tangentially related report from Nature. Blue-light exposure (screen light) shortens the lifespan of fruit flies and causes “brain neurodegeneration” and accelerated aging. So I quickly stopped reading and deployed the will to forget.

But the preliminary results of my own single-person study are almost as alarming. Once I’d turned the iPhone dismal and looked up at the non-screen world, it was as if the color from the phone had suddenly bled back into reality. Everything was brighter and lovelier — not metaphorically but literally. Subtle shades I hadn’t noticed were missing had returned, muted grays, browns, blues — the infinite variety of what should be the real-world spectrum.

This has scared me so much that I’ve firmly resolved to use what remains of my willpower to try to continue in black and white. Let’s see how long it lasts.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply