It was a hot late evening on the Greek island of Tinos, and we were sitting at a quayside restaurant outdoors, enjoying a nightcap glass of ouzo. One or two other tables were still occupied by diners, all of them Greek. Foreign tourism is only slowly coming back but Greece has a strong internal holiday market, and Tinos, a lovely island, is only an hour or two by ferry from the mainland.

A couple of children, small girls, were playing around the edge of the quay. The tranquil scene was now disturbed. The girls were looking in alarm at something under an unoccupied table. A big fish, beached, more than a foot long, was flopping around on the concrete, gasping. Other diners looked on, unconcerned, but I thought the children were distressed. In retrospect this could have been a mistaken assumption.

Nobody was doing anything. Acting on instinct and without much thought, I walked over, picked up the fish and threw it, wriggling, back into the sea. Then, supposing myself to have done the right thing, I returned to our table and my partner, and we carried on sipping ouzo and chatting. I should have asked myself how the creature had ended up on the quayside and whether it belonged to a fisherman, but I didn’t.

Some time later a Greek woman, substantial, in her sixties I’d guess, leaned over from her table and began to berate me in broken English. ‘Why you throw fish into the sea?’ she asked.

I didn’t really know how best to reply. ‘You should not,’ she said. I smiled embarrassedly. From another table a man shouted ‘Why you laughing?’ I began to understand that my behavior had seriously offended everyone around me. ‘You eat fish?’ asked the woman. ‘How you think they die?’ I honestly had no answer. At this point the waiter came over with our bill and I paid and slunk off. I had not been in any way threatened, but certainly made to feel unwelcome, and I sensed genuine and unanimous outrage. I felt no hostility to anyone, but I felt theirs. The incident confused me.

My confusion calmed as we walked back to the hotel. I was able to think the episode through and assess my own behavior. I’d been in the wrong. Doing nothing was an option I should have considered. Or, having picked up the fish, I could have tried to establish if it was (as seemed with hindsight likely) the property of anyone there who had caught it and wanted it back.

My haste to get the creature back into the water had been driven by the pity any non-fisherman may naturally feel for a beached fish, but I should have thought first about my fellow humans, some of them doubtless dependent on fishing, all of them sympathetic towards an activity important to the island and its non-tourist inhabitants. I don’t, after all, recall from the Gospel story that Christ sided with the fish. No, he suggested to Peter and his companions that they cast their net on the other side, and they brought in a tremendous haul. These fish too will have been flopping around and gasping for life.

To act on a humane impulse does not guarantee that the action is wise, even if that’s a plea in mitigation. So far (again in retrospect) so straightforward. Lesson learnt.

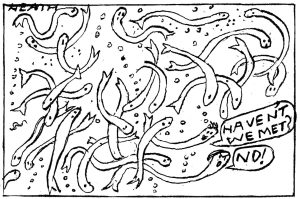

But another lesson remained unclear, and still troubles me. How do I answer the woman who asked rhetorically whether I eat fish? I do, as she guessed, and regularly. And I know how they die: it’s a slow, agonizing death, by the fish equivalent of drowning. Anglers may be able to put out of its misery each fish they hook — as in slaughterhouses we can kill beasts one by one and relatively humanely — but net fishing makes it impossible to concuss each fish individually, and on newsreels or at first-hand we’ve all seen huge hauls of live fish, wriggling, gasping, slowly dying. I hate to watch such scenes but they are routine, happening all around our coasts: part of the way of life of many brave and hardy fishermen whom we admire and whose livelihoods we urge our politicians to try to protect. For me this just doesn’t bear thinking about, and I try not to. I put from my mind the way a crocodile kills and stores a human child: typically they drag their prey underneath a submerged shelf where it dies as often by drowning as by mutilation. This is what we do to fish on an industrial scale, drowning them slowly, in air. Surely they suffer? And they are such beautiful, wonderful creatures.

The implication of the Greek woman’s indictment, whether or not she herself had thought it through, was that if I could not bear to witness in person the way fish die, I should not eat the fish others have killed for me. I cannot sidestep the logic. I reflected that refusing to eat meat but continuing to eat fish presents a logical challenge I cannot answer. Are fish really a ‘lower order’ of creation than (say) idiotic pheasants, or do we disregard their welfare simply because, unlike land-based mammals, they are very different from us? A carnivore, I find some justification in the thought that animal husbandry is a kind of partnership, otherwise we’d create a world where animals lived only in game reserves and zoos. But this argument is unavailable in the case of our planet’s marine life.

A non-pescatarian diet is something I could live with, but my partner, an excellent chef, loves cooking fish, and serves up for us dishes of which he is proud — and rightly: some of our best meals. Sharing our enjoyment of food is something that, for me, is a real part of a relationship, not least because cooking is one of his big things. Weigh that in the balance against my inability to give a satisfactory answer to the logical implication of a question from a random Greek woman whom I shall never see again, and I’ve no difficulty about which side I come down on.

But still.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.