Ishima, Japan

I’m halfway through a stay in Japan, the land of the free public toilet. City squares, riverside walks, bus interchanges in the middle of nowhere — chances are there’s one waiting. The grubbiest are old but clean enough. The cleanest are like operating theaters. I think of days in British cities where you have to draw up a dot-to-dot itinerary taking in that Starbucks (customers only); that department store (if it hasn’t closed down); that museum (entry £5). And I’m a guy: we have it easy, I know. Why is public provision for this basic bodily function so dismal across the UK? I keep hearing this vicious rumor it’s because councils no longer have the money to maintain on “discretionary spending items” like evacuating bodily waste. Call me a tofu-eating, “wokeist” Talking Britain Downer, but do you never get sick of systematically impoverished local government?

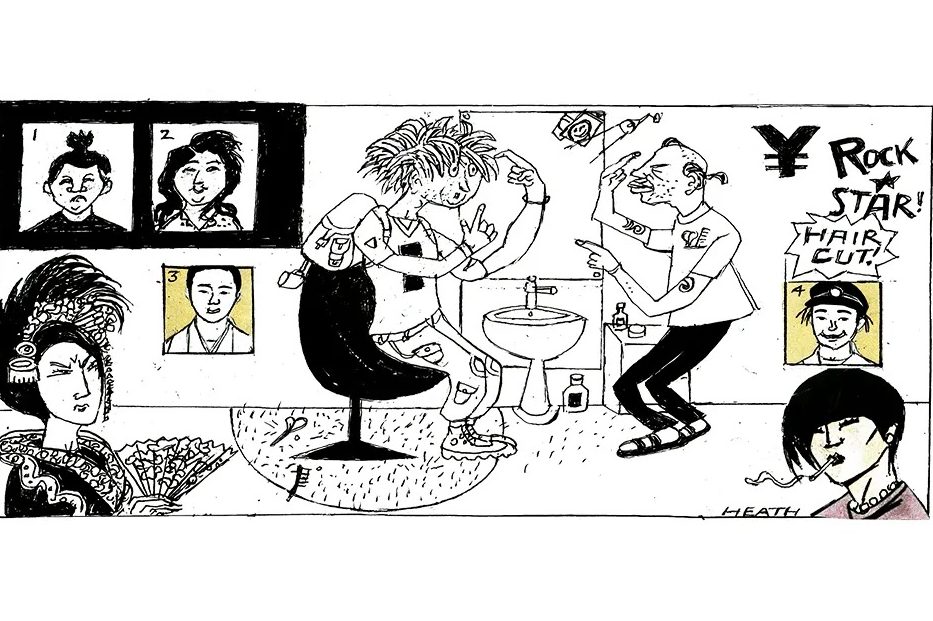

The days are getting warmer and my hair is getting longer, so I book myself in to my wife’s hairdresser’s off a quiet backstreet in Hiroshima. Only three chairs, black walls, no music and a blow-up landscape of a Sydney beach in a 1960s color grading. Whenever I sit in a barber’s, I think of a continuum of haircuts, like a Richard Linklater film, from my regular boyhood barber shop in Upton-on-Severn, to a suspiciously homophobic barber in Malvern, then Canterbury, London, Hiroshima in the 1990s — a different Japan to now — and two decades’ worth of trims at A Cut Above in Clonakilty. There were memorable one-offs in Delhi, Palermo, Chicago and a lake town in Sichuan where marijuana grew as vigorously as bracken. I remember a friend who died a couple of years ago and I wonder how many more haircuts I have left in the Book of Fate. May I remember to be grateful for each additional one.

The whippet-thin owner of the business has a focused Zen monkish air and a fluffy electric blue top which looks great on him but would make me look like a novelty gift item. He goes about translating my “short at the sides, a bit longer on top” into a presentable cut. When he compliments my Japanese, I’m reminded that I must try harder. In Japan, your language skills get complimented in inverse proportion to your actual level. Beginners are praised to the skies, but non-East-Asian-looking speakers who attain genuine fluency can really freak the natives out. Yoshi, my oldest friend here, has fun with this at my expense: “Wow, Dave, your Japanese was amazing before, but now it’s SO totally double SUPER amazing — what’s your secret?”

I enjoy collecting visits to off-the-beaten-track inhabited islands. Japan has 430, according to Google, which should last me any number of haircuts. This weekend I’m heading to Ishima, off the east coast of Shikoku. At Tokushima, I board a “One Man” — basically a bus on rails — to a small port an hour down the coast. Here I schlepp my backpack to the quay where the boat to Ishima comes and goes three times a day, weather permitting. It’s a small thirty-seater which I share with a few delightful hikers who hear “Iceland” when I say “Ireland” and are immune to correction. The crossing takes half an hour. Upon disembarking, I feel a cozy familiarity. The slow island time, the make-do-and-mend houses, the rickety old shrine to Ebisu, deity of fishermen. The semi-feral cats. The quiet. There are no cars on Ishima. There are no roads to speak of. My smiling landlord, well into his sixties, meets me at the quay to walk me back to the island’s last guest house, where he is the only staff and I am the only guest. He makes me a supper of seafood that was caught an hour ago. We talk about Ishima, his lifelong home, while I eat. Wikipedia puts the population at 190. My landlord tells me it’s now down to seventy. The island school is mothballed and there are no more kids. Whether there’ll still be anyone living on Ishima in twenty years is anyone’s guess.

I’m woken the next morning by a fishing boat chugging out of the harbor. I take a steep path out of the village, up through a camellia forest, through the rain so light it doesn’t really make you wet. A giant heron sits on a branch over a small green lake. There are toads the size of shrunken human heads. When I reach the lighthouse the sun comes out. The view over the wilder side of the island and the Pacific looks digitally enhanced. The birdsong is constant. The waves pound the rocks below. Across the globe and on the phone in my pocket, Putin is triumphant with Republican help, Trump Part Two is distinctly possible, Gaza is being pounded and dead people. Here there is this.

David Mitchell’s most recent novel is Utopia Avenue. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazines. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply