Chicago residents bristle when you ask them whether they eat deep-dish pizza. “Yeah,” they sigh, “we might occasionally when someone visiting wants to try it out.” Sigh. “We have great thin crust though.” But lots of places have good thin crust. I came to Chicago to try the deep dish.

But deep-dish pizza is stupid. It’s not a pizza, more a dense pie: the sauce sits at the top, and the filling beneath is quicksandy cheese. Sausage meat, jalapeños, chorizo, bacon, red onions and mushrooms are thrown into it and expected to learn how to swim. I got a deep dish on my last day in Chicago and found it wasn’t good. Not for any explicable reason — something like this can’t taste bad — but from my own somewhat pompous sense that God must be against it.

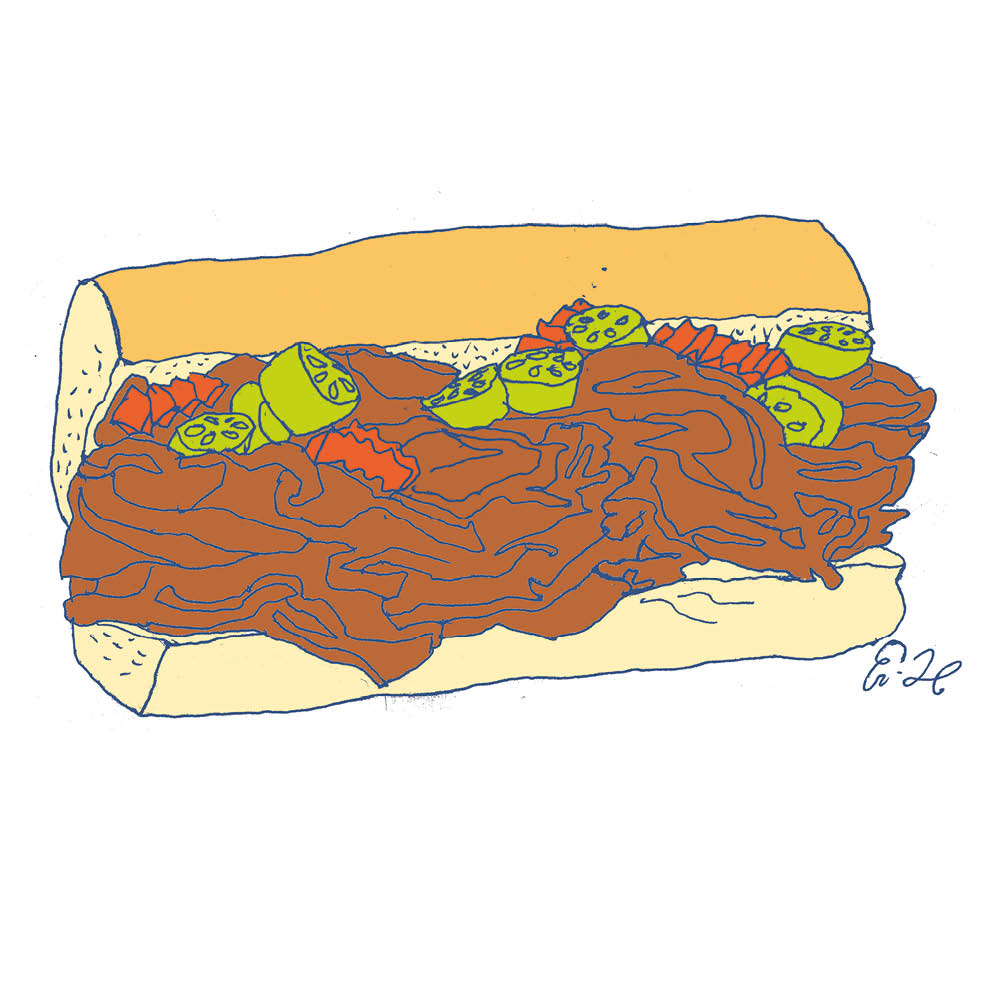

I hope He approves of the Italian beef sandwich, though. What a marvelous thing Chicago has given the world. Roast a load of beef so it shrinks up, then thinly slice it. Chuck it all into a beef broth, where it will sit for hours, stewing and plotting. Put it into a French roll, with hot peppers as well as green “sweet” ones, then dip the whole thing back into the gravy, so it gets “wet.” Eat it immediately so the paper it comes in doesn’t become an outer layer.

The sandwich’s “Italian” connection feels amazingly unclear, but Chicago’s Italian immigrant communities claim credit. I ate one at Portillo’s, a restaurant that, in my memory if not in reality, was covered in a dense fog from the condensation. Orders are boisterously shouted at customers (“number fifty-seven, come get your heaven!”). You can also get an impeccable Chicago-style hot dog there: beef sausage in a poppyseed bun, with mustard, onions, and enormous quantities of pickle. If you ask for ketchup, they throw you into Lake Michigan with two deep dishes tied to your ankles.

Chicago’s Italian beef has become known in its own right, thanks to The Bear: a TV show that follows Carmy, a Michelin-pedigree chef, who takes over the family Italian beef business after his brother suddenly dies. The Bear has done well, and Italian beef will do, since people now believe that caring about food makes them seem cultured. Don’t believe me? Look at the ceaseless rise of TikToks showing people careering around cities looking for the most hyped food spots. Everyone is invited to “join me” (the manic TikTokker) on “the hunt” for the best burger, or cinnamon bun, or Basque cheesecake in the West. Are these people employed?

A pub near me in west London — the Chancellors — started doing good pizzas after lockdown. Then an influencer said they were tasty and now getting inside is a Homeric struggle. People line up for two hours and come from out of town for a single slice of pizza. One day, I saw on the pub’s Instagram that they had sixty “walk-ins” available at 2 p.m. I live nearby, so I got there just after 2. They had sold out. In Chicago, tourists cross half the city not for a museum, but to go to Johnnie’s, the approved Italian beef spot.

It’s tempting to believe that this food craze represents how decadent and hollow society has become, but then I’d also have to accept that I too am decadent and hollow, because I enjoy it as much as the next TikTokker. Food is largely detached from politics, which is why it is so appealing. Italian beef sandwiches will be appearing all over the globe any minute now, and that’s not such a bad thing.

How will they taste, however, when divorced from the mustiness of Portillo’s and displaced from their Chicago context? There’s an aggression to the city’s food. Inside Chicago’s magnificent Peninsula hotel, we are shown the much-praised Chinese restaurant Shanghai Terrace, where Elmo Han serves up wok-fried scallops in black truffle sauce, and dong po pork belly. The chef, the hotel told us, only employs Chinese chefs, because he wants his kitchen to be staffed only by those who grew up “eating sticky rice.” Is that a little bit nativist? Maybe, but they just don’t care!

At the restaurant Proxi, we are served some delicious foie gras bao buns. Is that fusion? Or is it a chef thinking: “I’m going to put foie gras into a bao bun, because it’s obviously going to work — the soft bun gently hugging that fatty liver — and I literally don’t care about the cultural consequences.” The Italian restaurant Ummo has no qualms whatsoever about air miles. They import branzino from the Mediterranean, wood-fire it, drench the thing in salsa verde and capers and serve it whole: eyes frozen in death and face still gawping. At Carnitas Urupuan in the Pilsen neighborhood, they only offer three flavors of tacos: potato, potato and chorizo, and pork brain.

This slightly mad spirit was what I liked most about Chicago. I learned more about the city on the architectural river tour. In 1871, a huge portion of the city burned down and 100,000 people were displaced. There was no time for wallowing. The city was put under martial law for two weeks, and just like that, its residents invented the skyscraper. It’s no coincidence that the Burj Khalifa’s architect, Adrian Smith, is Chicago-born, and he is currently trying to better himself with the Jeddah Tower, which will be 600 feet taller.

In 1900, too much disease was coming into Chicago via the river. So they literally reversed the flow of the river. This is a city that puts its middle finger up to limits, and nature, and disaster, and chaotically and aggressively imposes its will on architecture, national politics (it spawned the US’s first black president), music and food. Like lots of second cities, there’s a drive born from resentment that you just wouldn’t find in New York.

When I got back to London, I tried to keep the trip fresh by reading a Chicago novel: Saul Bellow’s The Adventures of Augie March. He famously refers to Chicago as “that somber city” in the opening lines. If anyone in this untamed, unflagging city is somber, they really don’t show it.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply