“Paradoxes arise within an individual in proportion to their growing status or fame,” the author Stewart Stafford reminds us. Whether it’s the sexual peccadilloes of Bill Cosby or Harvey Weinstein, Lance Armstrong’s relaxed approach to his diet, or the apparent reluctance of certain well-known television performers to overdo it when it comes to wearing trousers in the green room, for many of our celebrities it seems that personal license is the rule and sustained self-restraint the exception. With each successive anniversary of their passing, the media always seem to wheel out yet another lachrymose account of the terminal unraveling of Marilyn Monroe or Elvis Presley, the fact that they continue to capture the public imagination evidenced by the latest Elvis biopic, with $280 million at the box office and counting. The reader may have his or her own candidate for inclusion on the list of all-American train wreck personalities.

For sheer self-destructiveness, however, none of the above could hold a candle to the chess grandmaster Bobby Fisher (1943-2008). His fall from grace was both acute and irreversible. Fifty years before Netflix produced The Queen’s Gambit, seemingly making chess sexy overnight, Fischer was already a household name to millions of people around the world who couldn’t tell their artificial castling from their elbow, and for whom the phrase Indian Defense conjured only images of the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre.

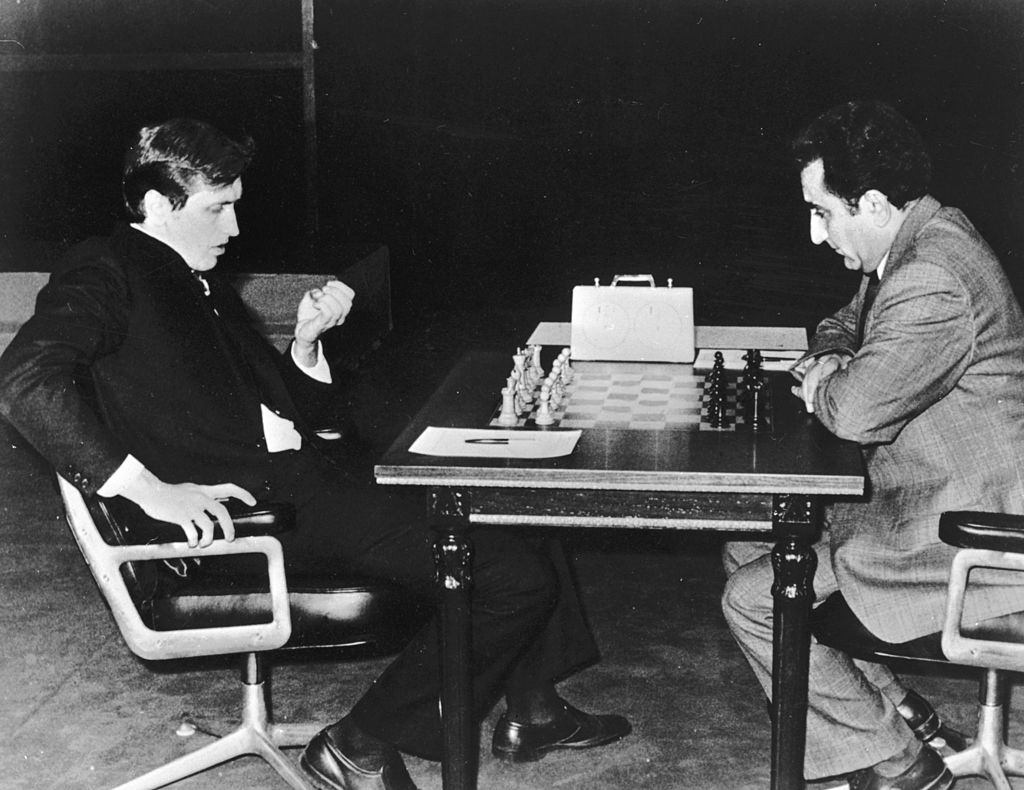

Fischer’s singular achievement came on August 31, 1972, when he comprehensively outplayed the supposedly invincible Boris Spassky of the USSR in Game 21 of a two-month long series held in a small Icelandic sports hall to become world chess champion. The next morning, Spassky phoned in to formally concede the title. To all but the readers of Pravda, the takeaway message was that of a lone American maverick overcoming the vast resources of the Soviet state. To give some idea of the scale of Fischer’s achievement, every world chess champion since 1937 had been a Russian citizen. The tournament was widely viewed as a Cold War triumph for the West, although even then there was something about Fischer that seemed to disqualify him from the full John Glenn ticker-tape treatment. The new world champion was offered numerous product endorsement deals, all of which he declined, although he did consent to a Johnny Carson interview in which Carson presented him with a 15 Puzzle, a grid composed of sliding numbered squares, similar to a Rubik’s Cube, that had baffled some of the world’s best brains since its introduction in the 1870s. Fischer solved the puzzle in seventeen seconds.

As with those other great disappearing acts, Garbo and Salinger, Fischer would go on to become almost as famous for his withdrawal from public life as he was for the achievements that brought him fame in the first place. He didn’t often speak to the press, and wasn’t a martyr to false modesty when he did. Fischer, who reportedly had an IQ of 182, bristled when a fawning reporter once offered the uncontroversial view that he was a genius at chess. “Bullshit,” he replied, not bothering to make light of it. “I’m a genius who happens to play chess.”

Born in Chicago, but raised in Oliver Twist conditions in New York, Fischer was brought up by his mother Regina, a card-carrying Communist who worked successively as a welder, riveter, nurse, schoolteacher, and toxicologist’s assistant. There’s some doubt about the identity of his father. One theory is that he was the eccentric Hungarian physicist Paul Nemenyi, a nationally renowned figure by his early twenties, who, if nothing else, would have ticked the genetic boxes marked “prodigy” and “tortured genius.” Fischer began playing chess at the age of six when his mother bought him a $1 plastic set. By nine, he was practicing and studying the game to the exclusion of all else. At thirteen he won the US Junior Championship, added the senior title at fourteen, and became the world’s youngest ever grandmaster at fifteen, already with a volatile temper and a tendency to turn up late or walk out of matches. He never lost a tournament (as opposed to an individual game) he completed from the age of twenty-two during the remaining forty-two years of his life.

Fischer’s shining moment came that summer of 1972, when at the age of twenty-nine he played the thirty-five-year-old Spassky in a bid to become the first US world champion in eighty-four years. The games weren’t televised, so chess experts painstakingly recreated the moves using oversized boards for the benefit of each evening’s network news broadcast. It seems barely credible now that through that long Watergate summer Americans with no prior interest in chess puzzled over poison pawns and bishop pairs as Fischer, after complaining about everything from the prize money to the hall’s overhead lighting, crushed the Soviet champion. People still talk about Game Six, in which the challenger outplayed his opponent from start to finish in a series of brilliantly unconventional moves that figuratively had the same effect as Muhammad Ali unleashing his rope-a-dope tactics against George Foreman a year or two later in Zaire. The win gave Fischer the lead in the tournament, and from then on Spassky never knew what his crazy opponent would do next. Fischer eventually won the title by a score of 12 1/2 to 8 ½. One of the three games Spassky won outright was due not to the brilliance of his chess, but because Fischer had refused to turn up that day.

Having reached the pinnacle of his profession before his thirtieth birthday, Fischer seemed to steadily lose his already fragile grip on reality. He refused to continue playing, and in 1975 forfeited his title to another Soviet master, Anatoly Karpov. By then Fischer was living out of a cheap Pasadena hotel room, in thrall to a sect called the Worldwide Church of God to which he donated a large chunk of his Reykjavik winnings. In 1978, he sued a magazine that had criticized the church, but then accused the church of reneging on a promise to finance the lawsuit.

Fischer eventually emerged from his self-imposed exile to again play Spassky, this time for the unofficial world championship, in a series of games held in war-torn Belgrade. He won the tournament 10-5, with fifteen draws. Fischer earned about $3.5 million for his trouble, but also the lifelong enmity of the US government, which had recently banned its citizens from any private or commercial activities in Yugoslavia. Asked to comment on the matter, Fischer held up a copy of the executive order in front of the watching press and spat on it. “This is my reply,” he said.

Now effectively stateless, Fischer was temporarily living in a modest guest house in the Philippines at the time of the 9/11 attacks on US soil. He immediately went on the air to share his views with a local radio station. “I applaud the act,” Fischer said. “Look, nobody gets that America and Israel have been slaughtering the Palestinians for years.” He added that he hoped for a military coup in the US. “With any luck, the country will be taken over by the army — they’ll close down all the synagogues, arrest all the Jews, execute hundreds of thousands of Jewish ringleaders.” This was perhaps the point where Fischer’s lifelong edge of paranoia descended into clinical madness, and he began to find his company more sparingly required by some of his closest former friends and admirers around the world.

In the end, only Iceland would have him. Fischer lived there quietly enough, although in 2006 he emerged to complain that the federal government was auctioning off his remaining US assets “worth hundreds of millions, even billions, of dollars.” The goods in question were some old clothes and books (among them a well-thumbed copy of Mein Kampf) abandoned in a California storage locker. For a time the Justice Department wanted to bring him back to answer for the Yugoslav-sanctions violation, but in the end he escaped the endgame of a public trial. Bobby Fischer died in January 2008, at the age of sixty-four, after a long illness. His last reported words, spoken to a friend as he massaged his painfully swollen legs, were: “Nothing is so healing as the human touch.” He received a full Catholic funeral, just as he had asked.