Blazing sunshine. Endless traffic. Horns honking. Wine bars heaving. Trance music blasting. Street hawkers calling. Coastal wind (called the “Cape Doctor” by locals) whistling. Grit in one eye, the other looking over my shoulder. Hair flying in every direction.

To explore central Cape Town is to be gut-punched: by an evolving backdrop of sublime nature and the complexity of the human condition. To visit the city’s world-class restaurants, concept stores and co-working sites is to share a street with the sick, hungry and homeless. Look up, and you’re hypnotized by the monolithic mountains beyond; a brief distraction from the painfully obvious disparity. From some angles it feels like the Mother City is being wrapped in a tight hug. Which is fitting, as I figure a lot of Capetonians could do with one.

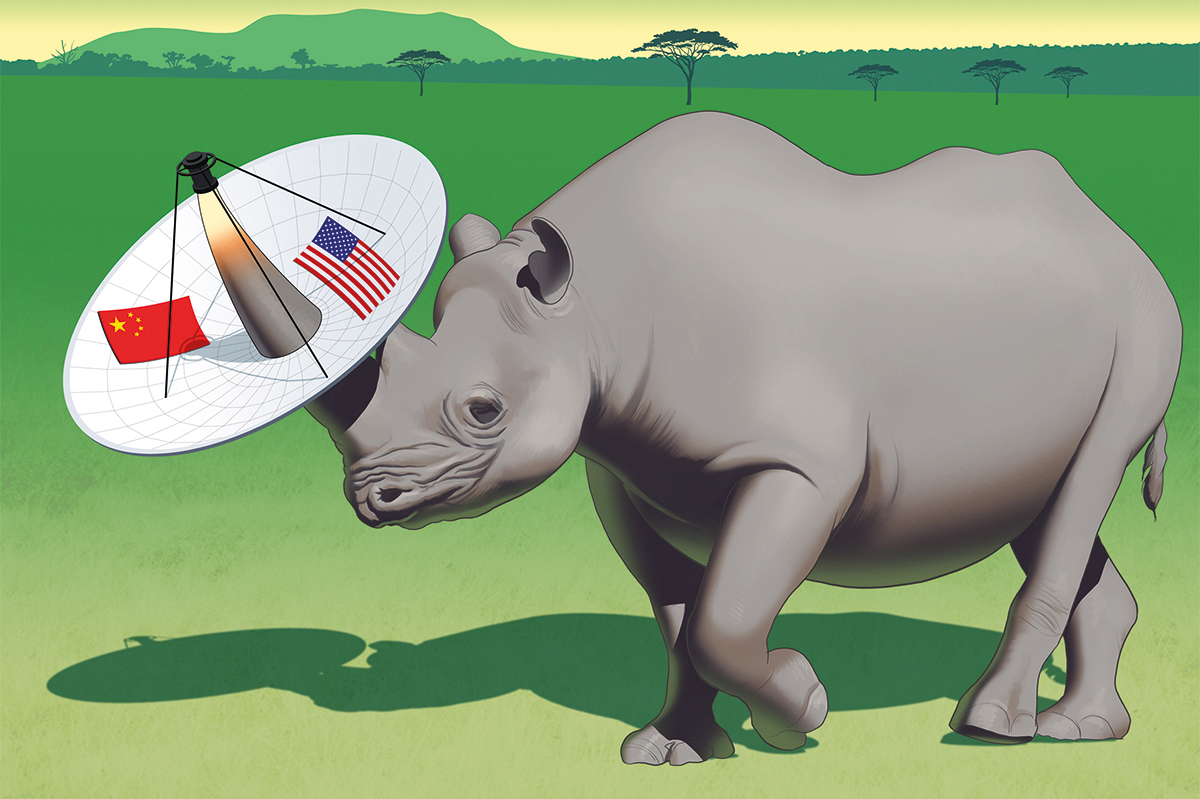

Covid delivered a fatal blow for so many businesses, and those that survived now face a new foe: load shedding. Planned nationwide power-cuts exponentially complicate things. Arriving in January 2023, it takes me weeks to fall into step. House alarms, coffee machines, traffic lights, fridge freezers, heavy machinery, sewage disposal… everything stops for hours, at varying times, every day.

Organic wine farms, idyllic beach clubs and lush nature reserves stretch for miles around. Immense work is happening behind the scenes to maintain each slice of heaven — and to continue to help those less fortunate.

I’m struck by small-business owner Michelle Fredman, who opened Sonder Café with her partner Chase Dell during the pandemic. Following two bouts of blood cancer and months of social distancing in London, Fredman chose Cape Town to set up shop. Then state power supplier Eksom increased outages to Stage 5. That can mean eight hours per day without electricity, for most locals.

Cozy cafés and guesthouses like Sonder stand defiant, rammed with the Dutch, Germans, Brits and Americans. They’re running on costly generators and inverters — if they can afford them — and that uniquely South African dynamism. It’s a trait honed across decades of tackling the unpredictable.

I download an app to plan around discomfort (no hot water for a cup of tea) and disasters (no WiFi to order a cab to the airport, or power to unlock a security gate). But the implications this has for restaurants and hotels? For people living in the townships that skirt the city? The mind spirals, if you let it.

“How do you do it?” I ask.

“The challenges of being a small-business owner are myriad in Cape Town,” Fredman says. “Our power is sometimes off for over four hours per day. An expensive inverter keeps our coffee machine running. On top of load shedding, we face the threat of crime, and of course had to try to stay afloat during lockdowns. Despite all of these obstacles we have somehow managed to persevere.”

Pulling up in the bohemian Observatory suburb feels raw; a more accurate picture of today’s Cape Town than the glossy V&A (Victoria & Alfred) Waterfront. Sonder Café’s pretty signage shines bright.

In a random moment of synchronicity, Fredman explains her business conceptualizes a feeling that had consumed me since landing. The café references a neologism in a whimsical book: The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows, by John Koenig. The writer dreamed up “a compendium of new words for emotions that we’ve all felt, but haven’t found the language to express.”

“Sonder” piqued Michelle’s imagination. It pinpoints “the realization that each random passerby is living a life as vivid and complex as your own… an epic story that continues invisibly around you.”

I’ve always grappled with the idea that I’ll never meet all the multi-faceted strangers out there, living experiences different from mine. I tell Michelle that South Africa is the sort of place those feelings manifest. She gets it, and we’re instant friends. I want to know everything.

Koenig’s words capture “the aches, demons, vibes, joys and urges that roam the wilderness of the psychological interior,” she explains. Whoa.

“After months in the hospital and very nearly having my life taken from me, I realized I wanted to spend my time with people,” she continues, “not sitting in an office.”

“I grew up beside the Atlantic Ocean in Cape Town. I backpacked around South America at eighteen. After a couple years abroad, I came back to Cape Town to study for my bachelors, and that’s when I began suffering from extreme fatigue and discovered a lump in my neck. It was lymphatic cancer.

“After completing six months of chemotherapy and my degree at UCT, I returned to South America where I ended up living and volunteering in the Amazon for two months. Then I worked as an English teacher in Ecuador for a year. After that, I returned to London to study for my masters in journalism. One month in, I was again diagnosed with aggressive lymphoma.

“After a year of undergoing chemo and immunotherapy treatments while completing my masters, I graduated with distinction and qualified for a stem cell transplant, which ultimately saved my life. After this, I survived six months at home during Covid, working as a copywriter while isolated and vulnerable. In October 2021, I decided to return to Cape Town to settle.”

These experiences naturally had a huge effect on Fredman.

“Both cancer and the pandemic undeniably shifted my perspective. I came home excited to squeeze the juice out of life, hungry for human connection and to pursue a project with meaning. Although I had zero experience in hospitality, my partner and I hoped to cultivate a space that’d bring strangers together during this time of unparalleled separation — through art, conversation, good food and coffee. A year and a half later, we expanded upon this idea by opening up a sister brand. Now we have a boutique guesthouse, Casa Del Sonder.”

Speaking of projects with meaning, Michelle and Chase work with local group GangSTAR to employ staff from impoverished backgrounds.

“It’s an amazing organization that rehabilitates and reforms previously incarcerated youths, by training them up in all things coffee and café management. Through GangSTAR we met TK — our incredible barista and now, brother. TK grew up on the streets, in poverty, and was introduced to drugs at an early age.

“This led him to a life of crime, and he was eventually jailed for housebreaking. After spending two years in jail, he was trained up through GangSTAR’s program. The organization helped him take responsibility for his life again. He’s living proof that anyone can completely turn their life around.

“TK is special because despite the obstacles he has faced, he is one of the most positive and hardworking people we know. His attitude is always one of happiness, commitment and pride in work, and he takes an interest in every single customer who walks through the doors.”

Most customers in Cape Town are tourists, and they’re having a ball.

“You can spend time outside, walking or climbing,” Fredman shares. Take the cable car up Table Mountain to witness the immaculate views. Paraglide off of Lions Head! Or simply swim or bathe in any one of our hundreds of gorgeous beaches. If you’re willing to brave the icy temperatures!”

“You can learn to surf at Muizenberg — a perfect beginners’ surf break. Drive the coastal road from Camps Bay, along the jaw-dropping Chapman’s Peak Drive, through to Noordhoek and Kalk Bay. Take a township tour and bear witness to the way the majority of our people live and co-exist. That’s an eye-opening and educational experience.”

Naturally, Fredman suggests her guesthouse as the place to stay.

“We found a beautiful, six-bedroom restored Dutch guesthouse on the fringes of Bo-Kaap, Cape Town’s historically Muslim neighborhood. This is where former slave houses were painted in bright colors after their inhabitants were granted freedom. It’s the oldest surviving residential neighborhood in Cape Town.”

“There’s too much to do!” I wail. What I now know to be “sonder” engulfs me. And Fredman’s not done.

“Hit the Oranjezicht City Farm or Biscuit Mill weekend markets. Go bar-hopping on Bree or Kloof street, have a picnic at Kirstenbosch Botanical Gardens, bathe with the penguins at Boulders Beach and go wine-tasting in our divine winelands.”

I’m already exhausted, but excited. What does Fredman wish everyone knew about her city?

“Cape Town is enchanting because of its extreme dichotomies. There is so much to absorb here, no matter your interests. We hope people come away realizing that this is a unique place, unlike anywhere else in the world.”

I soak up the beauty and history, and leave six weeks later feeling the same. Live wires like Michelle Fredman keep Cape Town fizzing with current — no matter how long the power’s out.