If it wasn’t for Chevalier Quixote Jackson, I wouldn’t be here today. Whether or not the Pittsburgh-born laryngologist and “father of endoscopy” knew it, 100 years ago his bronchoscope saved my grandfather’s life. The story, relayed to me by my grandfather and appearing in at least three New York City newspapers, is not only a fascinating one, but a window into an America that seems both distantly foreign and warmly home.

My mother’s father was of English and Irish extraction. His Irish ancestors — from whom he inherited the surname Fitzpatrick — had arrived in New York City during the Famine. The English side had also been in New York for generations, and apparently had some wealth. Both were Catholic, which has led me to speculate that perhaps his English family were immigrants with recusant ancestry.

Johnny, as my grandfather was called as a baby, was born in Brooklyn in 1922. He had an older brother and sister, though his brother perished in an auto accident just as cars were becoming common in the Big Apple. I still have that brother’s grade-school history book, complete with teenage doodles, published well over a century ago. From what I know, my grandfather’s early years, during which his father was a middle-class silk salesman, were relatively happy ones.

I’ve tried to imagine that Saturday in the autumn of 1923. My grandfather — though a man I knew only as a hardened old codger who served in World War II and started his own successful dental supply business — would have been a mere toddler crawling around on the floor.

One of the newspaper articles describes what happened next.

One moment, his mother noticed Johnny playing with the toy car. The next, she noticed he wasn’t playing with it. He wasn’t playing with anything. He was sitting very seriously on the floor and swallowing hard, with a faraway look in his eyes. He didn’t choke or gurgle or gasp. He just looked abstracted.

My grandfather had swallowed the pewter toy, which had come out of a Cracker Jack box. My great-grandmother rushed him to the family physician, who recommended she take him to “the Jewish hospital in Classon Avenue” (the hospital had opened to the public in 1906, and closed in 1983).

At Jewish Hospital, Brooklyn, Dr. J. Herzog took an X-ray of my grandfather’s throat, and discovered the toy lodged there. Using Dr. Jackson’s recently invented bronchoscope and the X-ray photograph, Dr. Herzog was able to delicately use forceps to extract the Cracker Jack toy from the baby’s throat. My grandfather was no worse for wear, and despite a heavy diet of bacon and butter, lived to be ninety years old. The hospital, the papers reported, held onto the toy as a trophy.

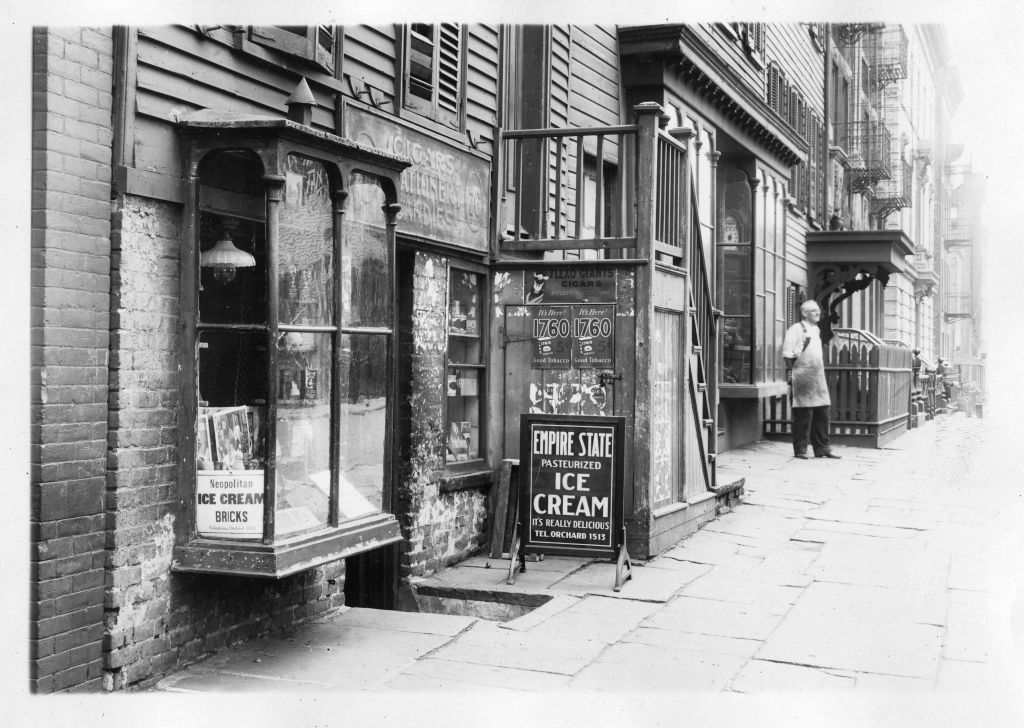

There are a lot of remarkable things about this story, starting with the ability of a doctor a century ago to draw a small toy out of a baby’s esophagus without performing surgery. Another is the media coverage, which was quite lighthearted and even comical, even approaching the poetic. One paper reported that the toy was discovered “in live storage.” Another began its story by reporting that my grandfather had gone back to his home “firmly convinced that his tiny throat was never intended as an automobile garage.” The papers even provided my great-grandparents’ address: 386 St. John’s Place, Brooklyn (I’ve never been, though I’d like to go one day).

Many years later, after my grandfather had sold his businesses and retired, he sent a letter to the company that made Cracker Jack (I’m not sure if it was Borden or Kohlberg Kravis Roberts, which bought Borden in 1995) explaining the whole story and including copies of the newspaper clippings. Whichever company it was, some corporate representative responded by sending him an apologetic letter and a lifetime supply of Cracker Jack. I mean just boxes and boxes of the stuff, with plastic toys inside each.

My grandfather joked that the company was trying to kill him so he wouldn’t sue. Of course, as a former small business owner and lifetime Republican who bemoaned the litigious character of American society, he had no desire to sue. He found the whole thing deliciously amusing.

As I’ve written elsewhere, my grandfather, whom I adored and respected, was a tough man. It doesn’t surprise me, then, how those New York City newspapers described him, even as a toddler. “He made no complaint,” reported the Brooklyn Standard Union. “Johnny didn’t even cry,” observed another. “It was plain he wanted to ignore the whole episode.”

The Jewish angle to the story also amuses me. At a time of increasing antisemitism in the United States, my Anglo-Irish grandfather received care from a Jewish doctor. Almost sixty years later, he would (very briefly) go into business with a Jew who had a very small dental supply store in Washington, DC. My grandfather had heard that a British conglomerate was buying up dental supply businesses if they had a certain net wealth, and he persuaded his Jewish competitor — also a World War II veteran who saw action in France — that if they joined forces, even for just a few months, they could sell the company and retire.

In its appreciation for technological ingenuity, in its journalistic joviality, and in its intersection of peoples from very different cultures and religions, this is a tale truly made in America. I wonder, though, whether Borden or KKR has any record of that letter my grandfather sent in the 1990s. Not that I or anyone else in my family would threaten to sue. But I do like Cracker Jack.