In retrospect I should have done it the other way round. When I mapped out the walk from my elegant Zurich hotel it looked to be about twenty minutes. What I failed to spy was the topography — and soon I was climbing a pretty serious hill through a high-end residential neighborhood. It was hot. I soldiered on, obviously appearing to the unamused Swiss on the sidewalk a weird and confused American, huffing and puffing and smoking. Then the little mountain plateaued into a blind road, a ball field and across from it the cemetery. Now it was just a matter of finding his grave.

No writer, possibly no person I have never met, has occupied as much time in my mind as James Joyce. I first read Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man at fifteen. I recall imbibing the scene where the spirited protagonist Stephen Dedalus places himself in the world, “Stephen Dedalus / Class of Elements / Clongowes Wood College / Sallins / County Kildare / Ireland / Europe / The World / The Universe.” It was just one of many of Stephen’s thoughts that passed from the page to my mind with a powerful familiarity.

My favorite high-school English teacher then guided me through Dubliners and the poems, but he would not let me read Ulysses. He said I was too young, that I wouldn’t understand it. At the same time he forbade me to apply to Irish universities out of a legitimate fear that I’d wind up a priest or a provo. But on the final day of my senior year, Mr. Reinke called me to his office in the old leafy Philadelphia prep-school campus and gave me a gift-wrapped book. A heavily annotated copy of Ulysses. I was ready. Maybe.

Fluntern Cemetery is a strange place. It is full of trees offering welcome shade. I am accustomed to American cemeteries with long rows of headstones on manicured flat lawns, or even the dusty, hot stone mausoleums of Buenos Aires. But here the graves just sat in nature, as if the headstones were merely another example of flora.

I had arrived in Zurich the night before with a fellow journalist and a couple of PR guys on a Big Tobacco junket. We had all had something of a late evening. But by now I had sweated out the toxins and felt a bird-buzzing stillness and breezy coolness. There was nobody at the cemetery save an uninterested groundskeeper. Aside from a few moderately prominent Swiss lawyers there is no one of great historical note — other than Joyce — interred at Fluntern. I wandered my way around, peering sometimes at the statuary.

Joyce’s mother died when he was twenty-one. Mine would die when I was close to that age, not long after I first read Ulysses, a consequential coincidence in my life. As the novel opens we find Stephen again. His mother is beastly dead, and he has refused her final wish, for him to renounce atheism and take communion. Her death very clearly hangs over not just the twenty-one-year-old Stephen but the forty-year-old James who published the work in 1922.

All Joyce’s work shows distance and disconnectedness. Joyce exiled himself from Ireland for almost all his adult life but wrote of little else. He defied the Catholic faith but would graft the lessons of Aquinas atop his tales. He often comes off as a jerk, overbearing and impulsive. But there is always curiosity and empathy, whether for the lost little boy of “Araby” or the whores of “Circe.” Joyce’s playground is human smallness, people’s jealousy and pettiness; in them he finds the deepest expressions of humanity — and even beauty.

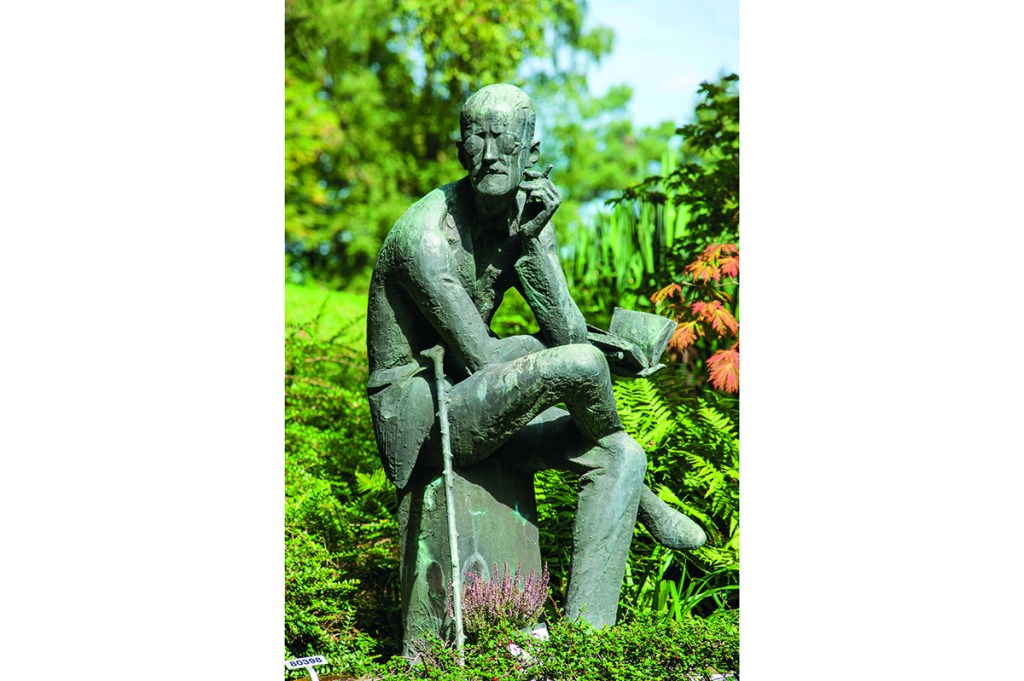

When I finally found it I laughed, — my idol was there smoking a cigarette and vaguely reading a book. There are very few who enjoy the slow, slender burning fuse of a Marlboro Light more than I do, so I sat on the little bench and lit my own. The statue is of dark metal, rough around the edges. Joyce sits cross-legged, eyes turned away from book, as if some phrase caught his interest and now he is gazing at it with his mind’s eye.

I found myself more profoundly moved than I would have thought possible. This was a man after whom I had modeled not only many elements of my own life, but an entire worldview, an entire purpose to living, to understand and feel and express. And here was his grave. Just bones beneath some soil; just a man after all.

I often feel grateful for my unabashed admiration and love for James Joyce. We live in an age when such things are frowned upon, when the measure of an artist’s or politician’s sins must always be taken alongside their triumphs. I don’t want to do that. And I won’t. I want to revere the men of the past; I want their wisdom and advice. I want tears to well as I contemplate their mortality and my own.

Years and distance were gone, as I took a photo of myself by his statue. (David Marcus and James Joyce / Fluntern Cemetery / Zurich / Canton of Zurich / Switzerland, etc.) Just as his words had conquered the distance of those dimensions for two decades in my mind, now it was so physically.

I took the bus back down the hill. I should have done it the other way round. There was a small gaggle of attractive women on it. I pulled out the international edition of the New York Times and tried to look serious and attractive. I think I just looked like an American. I don’t expect I will ever return to Joyce’s grave; I see no reason to. We shared our moment together, at least I did. And they aren’t just books anymore. Now they are the words of a friend.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 2022 World edition.