It’s a long climb up the 1,368 steps to the Shinto shrine at Kotohira. Many of the pilgrims are making comfort stops at the countless teahouses that line the route, but other worshippers break their journey at Kanamaru-za, the oldest surviving kabuki theater in Japan.

Kabuki, with its vivid stock characters, juicy plots and sumptuous costumes, has always been the most popular and accessible of the Japanese theatrical traditions. In the early seventeenth century performances featured both sexes, but in 1629 the ruling shogunate decreed that actresses (many of them prostitutes) were a danger to public morals and the art form became — and remained — an all-male preserve. A middle-aged man in Barbara Cartland war paint, heavy black wig and lavender kimono ought to be ridiculous but the kabuki heroine is a magical creature and a great onnagata (a male actor playing a female role) will transcend the conventions and carry you away to the floating world.

Sadly, Kotohira is fresh out of onnagata in June. Kanamaru-za is dark for fifty weeks of the year, coming alive for only fourteen days each spring, but the handsome wooden building is well worth the detour. It was originally crowd-funded into being in 1835 by a gang of local geishas who systematically short-changed their clientele until they had amassed the necessary cash. Like most old Japanese buildings, though, it is a lot newer than it looks, having been lovingly restored in 1976 using close-grained Japanese cypress and set out in the traditional masuseki style with spectators corralled into groups of four separated by low wooden rails. Spending four, maybe five hours on a thin cushion is no picnic but the kabuki stars who travel down to Kotohira every April relish the retro atmosphere: “Sitting on the floor, eating and drinking sake? It’s the origins of kabuki,” smiles Nakamura Ganjiro IV, who regularly features in the spring festival.

A decent stalls seat will generally set you back more than $130 — never mind the grand spent on your fourteen-hour flight — but things became easier for the kabuki fan this year when Shochiku, the 128-year-old company that manages and promotes Japan’s major kabuki theaters, introduced Kabuki on Demand. Its current screenings include a vintage 2009 performance of Chikamatsu Monzaemon’s 1703 work The Love Suicides at Sonezaki, featuring Ganjiro as the doomed oil salesman and his father, Sakata Tojuro IV, playing his fragrant teenage sweetheart at the age of seventy-eight. Multi-layered silks, a thick layer of whiteface and a vast repertory of simpers, sighs and nods transform the old man into the flower-like Ohatsu. When I first met father and son more than twenty years ago they were preparing to leave for a UK tour of The Love Suicides and I foolishly asked papa whether the women in his life informed his playing of teenage prostitutes. I was given very short shrift. “The whole thing is to idealize women: to make women who are more beautiful, more elegant,” explained the officially designated Living National Treasure. “You don’t really look to other women for that.” Ouch.

Tojuro, who died in 2020, performed the role of Ohatsu for more than sixty years, a triumph of verse-speaking and physical control. Chikamatsu’s text — he is regularly dubbed “the Shakespeare of Japan” — is half-spoken, half-sung in a wavering falsetto, first cousin to the pained miaow of Peking opera. This Pythonesque squeal takes a bit of getting used to, but the uncomprehending spectator is soon caught up in the tragic tale and its many ravishing set pieces, notably the chilling moment when the heroine hides her lover beneath the brothel’s verandah and shudders almost orgasmically as Ganjiro draws her naked foot across his neck, prefiguring their mutual destruction.

The Love Suicides at Sonezaki was based on a real case and its success triggered an outbreak of double suicides (seventeen in 1703 alone), prompting the shogunate to ban the play. Suicide is undoubtedly a recurring theme in classical Japanese drama and in May this year art and life collided with the grim news that kabuki superstar Ichikawa Ennosuke IV had been found unconscious in a cupboard at his home while his elderly mother and father lay dead and dying upstairs under a futon. A women’s magazine had just accused Ennosuke of bullying and predatory behavior towards colleagues and he had seemingly opted for death rather than dishonor. He was arrested last week on suspicion of assisting his mother in her suicide.

Japanese news stories seldom make the foreign pages but this samurai code stuff was a neat fit for the lazy stereotype of Japan as a suicide-prone society. (In fact, according to WHO figures, it’s in forty-ninth place for global suicide rates behind both the US and Belgium.) The only other story scoring comparable column inches was the ludicrous “report” that Japanese people were signing up for smiling lessons now that mask-wearing was no longer compulsory.

Consciousness of the Ennosuke case adds a certain frisson when watching Chikamatsu’s tragedy (“only death can wash away the stain of disgrace”) and to the “meta” moments in the text: “If they made a drama out of my life and staged it people would surely have sympathized.” The handy translation is penned and voiced by art historian Paul Griffith, whose sensitive running commentary outlines the story and explains the mysteries of the staging to the kabuki newcomer.

Ganjiro is all in favor of the audience-building potential of Kabuki on Demand: “Ondemando is definitely an opportunity for kabuki fans to watch more, but the biggest strength is attracting new people.” I wonder if the filming cramps his style. Any actor used to projecting to the back of the stalls can risk looking hammy on screen, yet Ganjiro has never considered recalibrating his delivery: “I don’t change my way of acting whether the camera is there or not.” It has, however, crossed his mind that the unforgiving close-ups risk shattering kabuki’s illusions: “The great thing about kabuki is that males can play the role of females, old people can play young people but the camera shows everything so clearly that I am a little bit concerned that that might become a problem.”

Ganjiro made his stage debut at eight and worked his way through a variety of roles before specializing in “wagoto” characters, sensitive heroes who perform in an almost naturalistic style. Was this a reflection of his own temperament? The actor, smart casual in his slate-grey haori jacket, rapidly disabuses me of this sappy Western idea: “The parents decide which roles to play. The parents and the production company. The actor doesn’t choose.” Kabuki runs in families — Ganjiro is fifth generation — but the various stage names an actor is given during his career are also bestowed for artistic rather than purely dynastic reasons, rather as if a Shakespearean actor were to be rechristened John Gielgud III after a particularly fine Hamlet.

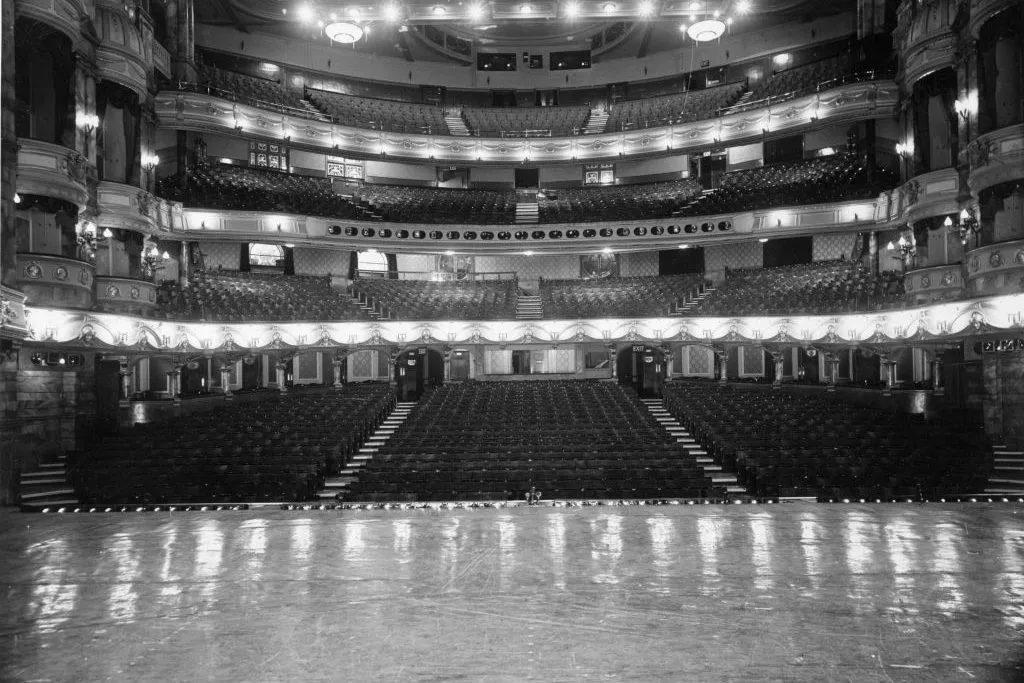

Ganjiro’s powerful performance in The Love Suicides on demand whiles away the five-hour train journey from Kotohira to Tokyo where I treat myself to an all-day matinee at the capital’s vast 2,000-seater Kabuki-za which is presenting popular scenes from the back catalog. The audience, including a huge party of sailor-suited schoolgirls, was clearly familiar with the material, applauding key entrances and encouraging the actors with shouts of praise or recognition. These spontaneous-seeming cries are in fact delivered by omuko-san, a guild of seasoned enthusiasts who maintain the tradition in exchange for free seats in the gods. They give very good value, particularly when an actor pauses on the hanamichi catwalk that runs through the stalls and slots into a well-known pose, or mie. Virtually every mie has been immortalized in one of the famous ukiyo-e woodblock prints of the Edo period. Reproductions can be found on the sake cups, T-shirts, hankies and fridge magnets on sale in Kabuki-za’s bustling gift shops. It may look a lot like a tourist trap but the customers are all Japanese.

Visitor numbers are only gradually inching up since the country reopened for business last October and the theater hasn’t got around to supplying the usual English language headsets — a visitor-friendly service that had been available since 1982. In near-panic I struggle to memorize a convoluted synopsis — a suicidal artist, a marauding tiger, a kidnapped princess — then realize that watching without the explanatory earworm offers a chance to savor the sheer artistry of the performance — like opera before surtitles. Suddenly I can focus on the strange music of the vocal delivery, the symphony of color, pattern and texture in the exquisite silks, the time-honored sways, nods and gestures that bring these ancient stories to life.

Kabuki on Demand can be found at kabukiweb.net. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.