In 1993 Vernor Vinge popularized the notion of the Singularity — the point at which exponentially accelerating trends in multiple technologies move out of control in an endless positive feedback loop. Vinge was a science fiction writer; Ray Kurzweil is not. In 1993 he had already pioneered optical character recognition and synthesizers that could precisely mimic real instruments. His mission crystallized into making Vinge’s conceit a reality. He is principal researcher and “AI visionary” at Google — and principal proselytizer, too, through any number of portentously titled books.

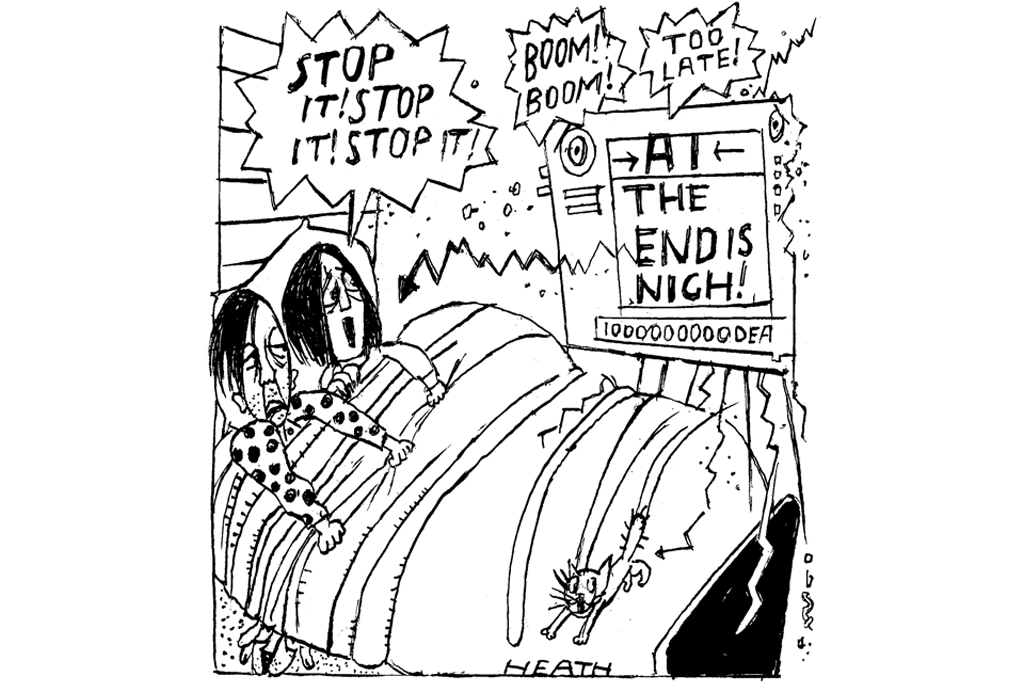

The Age of Spiritual Machines (1999) set out his stall; The Singularity is Near (2005) staked a claim for human-level intelligence in computers by 2029 and a generalized apotheosis in 2045. So, on his timescale, we are roughly half way between 2005 and a third book in the trilogy, presumably The Singularity is Now — although by that time no one will be reading books because adaptations to our neocortices will mean that all the world’s information will be available to everyone, everywhere, immediately, inescapably.

Faced with this prediction, the obvious questions are: will this happen? Will this happen on this timescale? And will the world be better as a result? Yes, says Kurzweil, and yes and yes. The least interesting parts of the book run a victory lap on his previous predictions. Twenty years ago he was regarded as wildly over-optimistic about the possible pace of change. Now, compared with a lot of Silicon Valley boosterism, he looks conservative. It is a truism of futurism that we overestimate changes in the short term and underestimate them in the long. Since 2005, the compounding effect of two decades of Moore’s Law (that computer power doubles roughly every eighteen months) has brought in its revenges. In 2005 a dollar would buy you around 12 million computations per second. Today that number would be around 48 billion.

Timetables being what they are in book publishing, some of Kurzweil’s commentary on AI and Large Language Models feels almost quaint, as the technology has been so widely covered. (LLMs, in particular, are coming for the livelihoods of white-collar workers who use words for a living, so, unsurprisingly, those people have paid considerably more attention to the transformation than they did when technology was replacing manual work.) Recent research by Epoch AI suggests that AI improves by a factor of just more than four every year — so by 2029 it could be more than 1,000 times as powerful as today.

More contested are the social effects of the Singularity or at least the run-up to it. This comes as a combination of interlocking technologies, principally advances in computing power fueling AI; nanotechnology; and life extension. Kurzweil’s argument is that over the broad sweep of history, technology makes people’s lives better and more rewarding. Literacy is up; perinatal mortality is down; solar power is spreading rapidly. Democracy is becoming more embedded (although the record of the last two years has put that into reverse).

The effect on jobs is shrugged away, as is easy if you take a sufficiently long view, although that long view is not one in which anyone’s life is actually lived. He makes a case for the importance and desirability of life extension: more life in good mental and physical health is an unalloyed blessing and life extension offers that kind of old age rather than eternity as a Struldbrugg. From there he hops to the belief that soon aging will be a can that can be kicked down the road indefinitely. If 100-year-olds in the next decade start living to 150, that offers fifty more years to solve the problem of living to 200 and so on. Kurzweil was born in 1948, so feels the timelines of this particularly acutely.

His penultimate chapter flags up some existential threats to humanity and therefore to the Singularity. There could be a nuclear war. New biochemical threats could emerge. Nanotechnology could reduce the world to a gray goo. AI itself could run rogue. But he pronounces himself “cautiously optimistic” AI makes these problems easier to solve: “We should work towards a world where the powers of AI are equally distributed, so that its effects reflect the values of humanity as a whole.”

That sentiment is precisely where The Singularity Is Nearer, for all its limning of technical possibilities and its Panglossian extrapolation of back-of-the-envelope calculations into visions of a transhumanist future, fails to make its optimistic case convincingly. Kurzweil is a master of all sciences except politics. When he hymns the possibilities of 3D-printing, he notes in passing the dangers of 3D-printed guns invisible to scanners. His considered conclusion: “This will require a thoughtful re-evaluation of current regulations and policies.” Well, indeed. More broadly, when he discusses distributional issues, his premise is that the “idea that wealthy elites would simply hoard this new abundance is grounded in a misunderstanding.” Has Kurzweil never met any of the wealthy elite?

Every single technology discussed in the book will in the short term create losers faster than it creates improvements for society as a whole — not to mention a whole realm of unpredictable unintended consequences. And the capacity of political systems to navigate challenges of that sort has not, to put it mildly, been improving exponentially.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply