Post-war British economic history is littered with failed policy panaceas. Keynesian demand management would solve the unemployment problem; the exchange rate mechanism would provide an anchor for stability and end sterling’s perennial weakness; the Barber and Kwarteng budgets — separated by fifty years — would throw off the shackles of treasury orthodoxy and put the country on a path to higher growth.

On the face of it, monetarism — the theory that if you control the money supply, you control inflation — fits squarely into this paradigm. As soon as government sought to control the money supply, the historic relationship between money and inflation broke down. But partly because inflation did come down, albeit at the cost of high unemployment, and partly because its politics remains a dividing line between left and right, monetarism still represents disputed territory — the more so because of the Bank of England’s recent experiment in so-called quantitative easing.

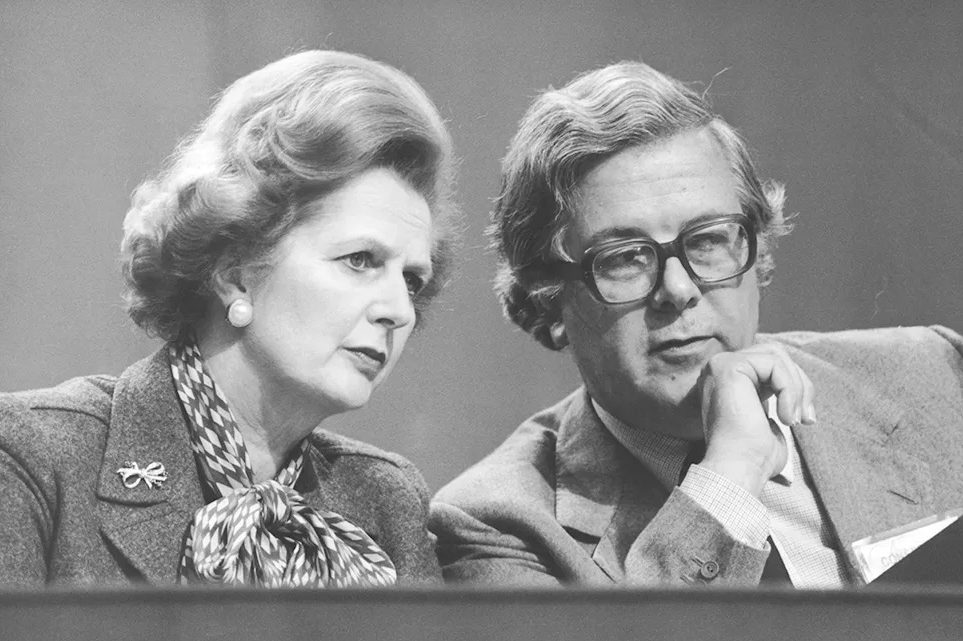

Tim Lankester’s book, Inside Thatcher’s Monetarism Experiment, is therefore a timely review of the high-water mark of the monetarist experiment. The author had a ringside seat. Not only was he Margaret Thatcher’s private secretary when she was prime minister, responsible for economic affairs, but because Thatcher chose not to appoint an economic advisor, preferring to rely on her treasury ministers Geoffrey Howe and Nigel Lawson, he was the only economist working in No. 10 between 1979 and 1981.

Lankester describes himself as a “disbelieving monetarist,” someone who went along with monetarism because the markets believed in it even if he didn’t. But he admired Thatcher, and was all too aware of the failings of economic policy under Edward Heath, Harold Wilson and James Callaghan. He’s a reliable witness. And his analysis of where monetarism went wrong is compelling.

The first problem is that money is a slippery concept. Is it simply notes, coins and the reserves created by central banks? Or is it something wider, taking in current and deposit accounts held within the broader banking system? The narrow definition is easier to control. But it is the broader definition that monetarist economists observed had the closest relationship with inflation.

Containing growth in the money supply proved much more difficult than expected. Interest rates were an imperfect instrument. In the short run, higher interest rates tended to increase borrowing by businesses as they responded to a downturn in demand for their goods and services. And though abolishing exchange controls and wider restrictions on bank lending was the right thing to do since it further liberalized the economy, it distorted the relationship between the money supply and prices.

And instead of tempering their wage demands in response to monetary targets, as some theorists predicted, trade unions increased them. Here, the wider context did not help. The near doubling of VAT in Howe’s first budget, Thatcher’s decision to implement in full the Clegg commission’s recommendations on pay comparability, and the wider effect of the second oil crisis led to a doubling of inflation in the Tories’ first year in office.

In the end, it was old-fashioned deflation, in the form of high interest rates and a succession of restrictive budgets, which brought inflation under control. As Milton Friedman, the high priest of monetarism, later observed: “The use of the quantity of money as a target has not been a success.” And by the mid-1980s, Lawson, if not Thatcher, was looking to the exchange rate rather than monetary targets to provide an anchor for economic policy.

Ultimately, it was the microeconomic changes — such as the curbing of trade union power, tax reform and the ending of industrial subsidies — rather than monetarism that transformed British economic performance in the 1980s. Lankester argues that had the Thatcher government implemented trade union reform as a precursor to monetarism, history might have been different. Certainly, greater flexibility in the labor market has resulted in more recent economic shocks, such as 2008 and 2020, having a much smaller impact on unemployment. But tactically, Thatcher made the right call in waiting for the unions to be weakened by recession before taking them on. And arguably the only way to reduce inflationary expectations once and for all was a severe deflationary shock.

But by restricting demand, deflation will generally contain a strong monetary element. And in this respect Lankester underestimates the importance of money and credit. He goes on to argue that quantitative easing has little to do with the recent return of inflation, but ultra loose credit conditions surely enabled the double digit inflation of 2022-23.

Purists will argue that it’s inappropriate for a civil servant to write about his time in government. And I have some sympathy for this view. But in Lankester’s defense, he is writing more than forty years on. All the papers are in the public domain. And, though very readable, this book is more for policy makers than for the mass market. There is little gossip and few jokes, apart from a humorous aside about a conversation between Callaghan and his minister for weather, Denis Howell. But it’s an important contribution to economic history. Thatcher rightly observed that economics is not a science. At best, it’s a set of principles, supplemented by a set of ever evolving relationships. And so when it comes to economic policy making, history is probably the best guide there is.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply