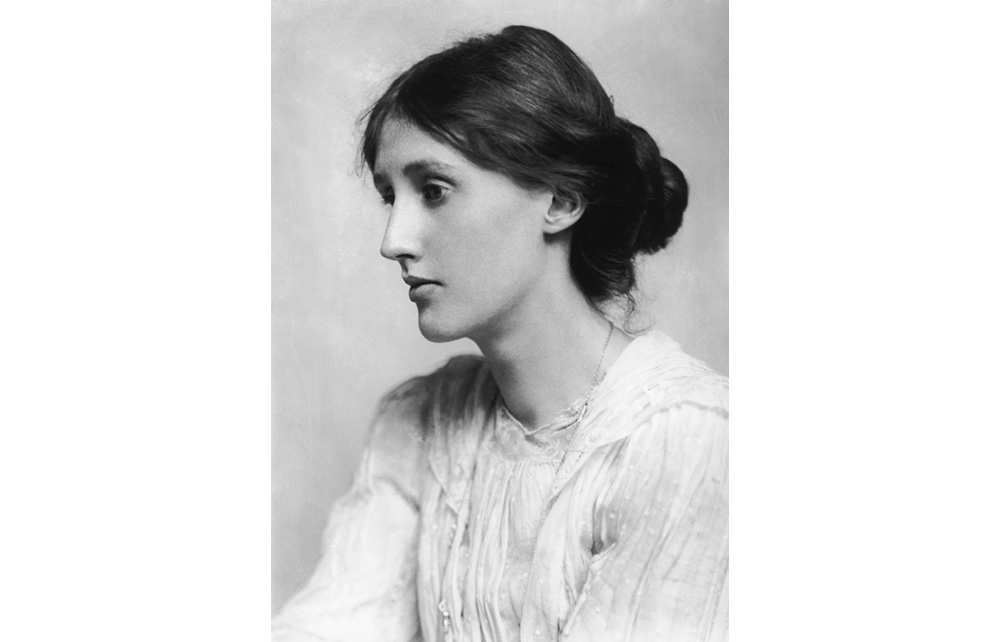

“Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself.” Nine words into her 1925 classic, Virginia Woolf has taken us to another world. London — Westminster to be precise — in mid-June 1913, a world in which it is unusual for a woman to buy the flowers for her own party. Clarissa Dalloway only steps out into the early morning air (“fresh as if issued to children on a beach”) because her maid, Lucy, “had her work cut out for her.”

The Wednesday in the “middle of June” on which the action of Mrs. Dalloway takes place is debated. The year is 1923, which would make the 13th of June the most likely candidate. But as academics are wont to do, there has been some disagreement. Woolf describes a quintessential fixture of the English summertime, a country cricket match (“Surrey was all out once more”). But the dates of this particular cricket match would put the action between June 18 and 20 1923 — not quite the middle of June, and more late June.

If you are wondering why the specific date of Clarissa Dalloway’s day matters, then bear with me. Who cares when she bought the flowers, fixed a green dress which some oaf had torn “at the Embassy party,” had a nap in a starched narrow bed, and reminisced about a first lesbian experience (“Had that not, after all, been love?”)?

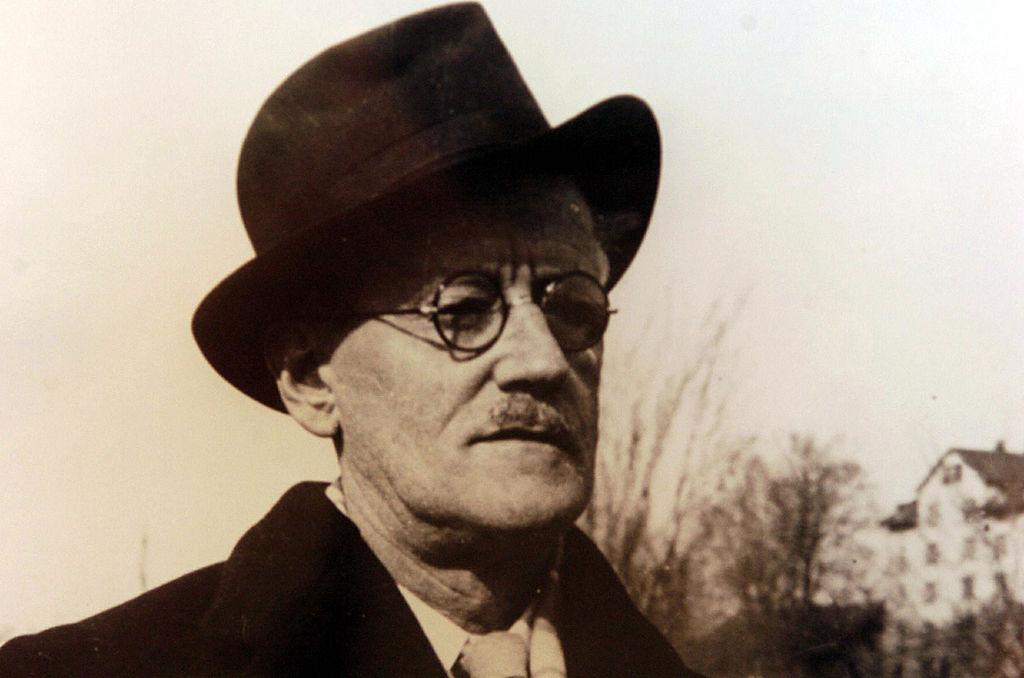

Devotees of James Joyce’s Ulysses — another modernist novel which is set over one day in June — have no such qualms or difficulty. Joyce was not so coy about his choice of date. Leopold Bloom wanders the streets of Dublin on June 16, 1904 — as Molly Bloom luxuriates in bed, Buck Milligan swims, and Stephen Dedalus broods. It is this particular day which has been, in part, responsible for the book’s longevity. The first “Bloomsday” was celebrated in 1954 when the poet Patrick Kavenagh and novelist Flann O’Brien made a rather boozy tour of the Martello Tower, and the pub and house on 7 Eccles Street described by Joyce. As “Bloomsday” became an event — an excuse for a night as raucous as Stephen Dedalus and Leopold Bloom’s — the reach and popularity of such an impenetrable book increased. In his recent book Consuming Joyce, John McCourt goes as far as to argue that Joyce has become a tourist product for Dublin — and Bloomsday is certainly something to be “consumed.”

The similarities between Ulysses and Mrs. Dalloway are undeniable: one day, one city, and a revolving cast of characters whose lives intersect as the hours wind on. But despite the fact that Mrs. Dalloway appeared with the Hogarth Press in May 1925, three years after the first complete edition of Ulysses was published by Sylvia Beach in Paris, Virginia Woolf might not have been all that comfortable about the similarities between her book and that of her Irish peer.

Her letters and diaries about Ulysses are scathing. On a hot September day in 1922, Woolf reached the “last immortal chapter” of Joyce’s book, after months of railing against “such tosh” of chapters which are “merely the scratching of pimples on the body of the bootboy at Claridges.” But instead of being swept up in the orgasmic “Yes, yes, I said yes” of Molly Bloom’s final monologue, Woolf is more interested in “Badmington [sic] in the orchard” and the necessity of changing for dinner. It is, of course, literary criticism sacrilege to identify an author with their character, but here, surely, is a moment of Clarissa Dalloway’s famous snobbishness.

Still, Woolf was more measured in her public response to Ulysses than her private diaries might lead readers to expect. In her 1919 essay “Modern Novels” — by then Ulysses had started to appear, serialized, in the Little Review — she lauds Joyce as “the most notable” of “several young writers” who attempt to “come closer to life” and “preserve it more sincerely” than their Victorian predecessors.

But why does the similarity — wanted or otherwise — between Joyce and Woolf matter? It is here that we return to the question of the unknown day of Mrs. Dalloway’s pre-party activities. Last year, Wednesday, June 16 was both Joyce’s Bloomsday, and Woolf’s Dalloway-day: the modernists were reunited once again. This year, as the sun goes down on Clarissa’s party on June 15, it will come up again on Leopold Bloom’s breakfast of burnt kippers and Buck Milligan’s shaving routine on June 16.

But while Bloomsday is a global festival spanning two days of exhibitions, readings, tours, and performances, rather less is happening for Mrs. Dalloway. The Royal Society of Literature is hosting a panel talk with New Yorker critic Merve Emre, Kabe Wilson, Elaine Showalter and Irenosen Okojie about the party at the heart of the novel, and Hatchards — the famous, brilliant bookshop in Piccadilly that Clarissa dreamily looks through the window of — is hosting a walking tour of Clarissa’s Bond Street and a panel discussion about Modernist Women Writers.

While it might not be quite on the scale of the Joyce appreciation, these events are still a celebration of Woolf’s work and her dedication to recording — in such brilliant interior detail — the modulations and occurrences of one day. But call me a philistine: I can’t help but think there is something missing here. The first Bloomsday event was famously raucous and drunken, and Mrs. Dalloway does — despite the intense melancholy — have a party at its heart.

So this Wednesday, I propose a different kind of homage to Woolf’s masterpiece. Leave the academic nit-picking and bookish ponderings for the other days, and instead — wherever you are — take a leaf out of Clarissa’s book. Buy some flowers for a party, fondly reminisce about your pre-war sapphic love affair, lament the decline in affections of your husband, and don’t forget to be a nearly ungovernable snob. And, most importantly, enjoy “life, London [or anywhere else]; this moment of June.”

If you take Clarissa’s day to heart — with all its wartime memories and persistent malaise — it may well not quite be “a lark! What a plunge.” But as literary days go, it could be worse. Anyone up for commemorating Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s 1962 classic One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich? No? Really? Just me? Suit yourselves.