There is nothing new about Latin America’s fractious relationship with her northern neighbor. In 1900 the Uruguayan writer José Enrique Rodó published an essay in which he pitted the spiritual in the form of Latin civilization (Ariel) against the utilitarianism and materialism of the United States (Caliban). Ariel may have been an overblown image but, by trying to construct a pan-Latin American identity, it changed the way Latin Americans thought about themselves.

Only two years earlier the Spanish defeat at the hands of the United States in Cuba had hardened the continent’s intellectuals against what they saw as North American aggression. When the United States helped Panama secede from Gran Colombia, Rodó called it ‘an international policy of usurpation and plunder’. He was not wrong. There was of course a vested interest for the United States in having this narrow isthmus between North and South America become independent: the construction of the Panama Canal.

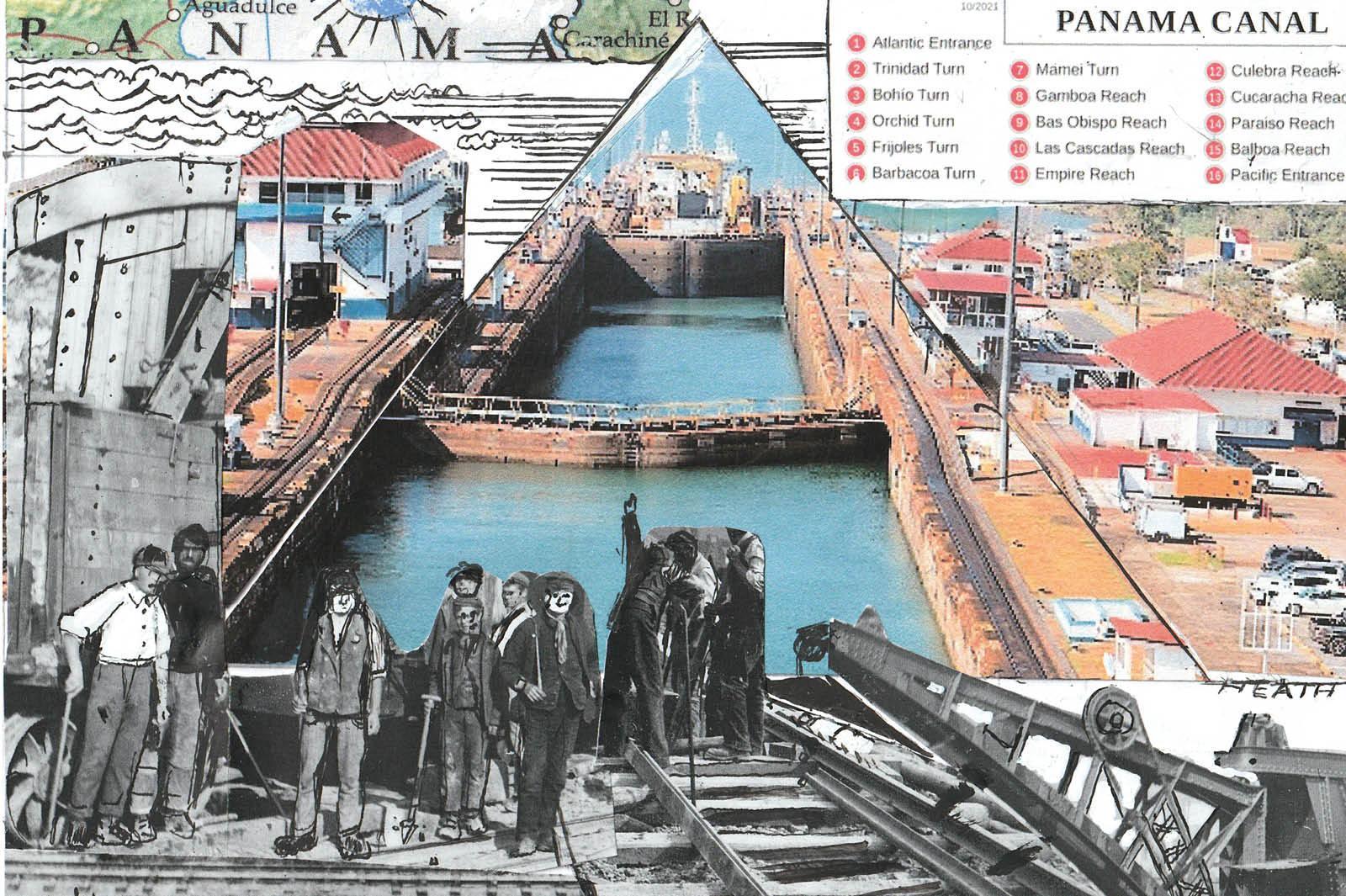

The isthmus of Darién had defeated a succession of Spanish explorers, including Christopher Columbus on his final voyage, before Vasco Nuñez de Balboa became the first European to cross that strip of land to the Mar del Sur (South Sea). This favorable quirk of geography turned what might otherwise have been a jungle backwater into an international hub. As Marixa Lasso states early on in this stimulating, though at times overly academic, investigation into the socio-economic effects of the man-made waterway, ‘global trade and global labour had been at the centre of Panama’s economy since the 16th century’.

In the 1820s, a French explorer noted the sophistication of the local inhabitants in terms of taste and the abundance of imported goods from the United States. By the late 19th century, the region’s ports had become the beneficiaries of modern technology and communications, either at the same time or shortly after their adoption by North America and Europe. The ill-fated French attempt at building a canal may have brought technological advancement but it ended in bankruptcy and the deaths of more than 20,000 laborers. (Malcolm Lowry would later write: ‘Hot here as a Turkish bath in hell. Jungle has to be chopped every day.’)

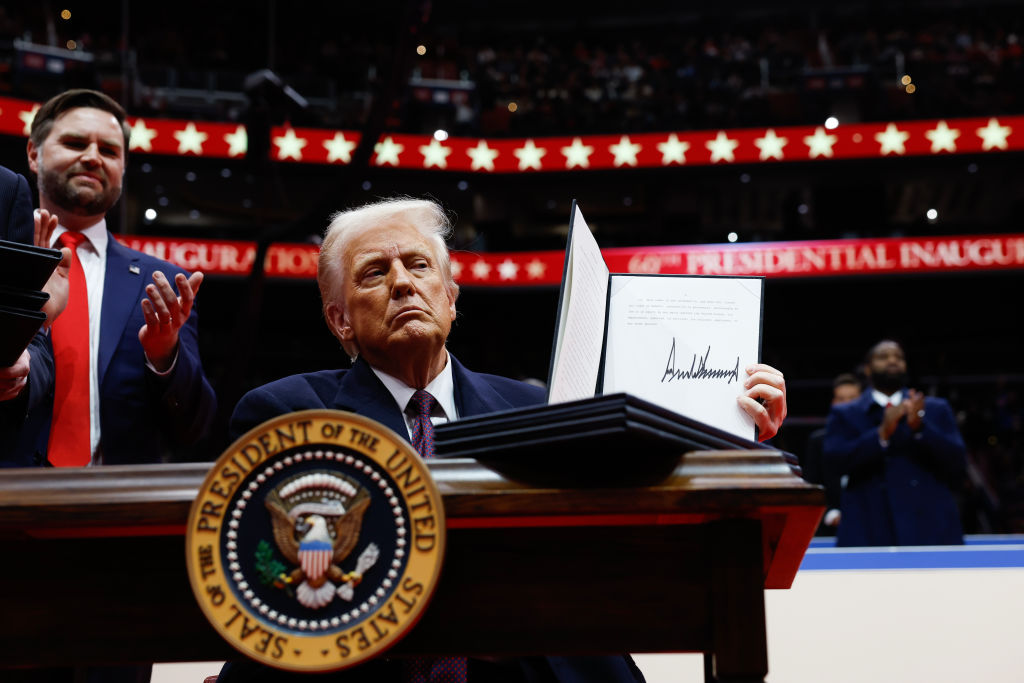

Where the French had failed the United States would succeed. In 1904, construction of what Theodore Roosevelt called ‘one of the great works of the world’ started; it would take a decade to open. On either side of the canal was a five-mile-wide strip of land, called the Zone, which the US had obtained under the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty. It was through this slice of America that the Italian-born Panamian Marixa Lasso was driven as a child by her parents on family outings. ‘There was something magical about the contrast between their jungle and the towns with the impeccable lawns, swimming pools and air-conditioned houses.’

The Zone was also a place of ‘desire and denial’: Panamanians were not allowed to use its amenities without invitation by a Zone resident. Prompted by these early recollections, Lasso has written a history of the lost towns of the Panama Canal and the attempt to quell the jungle and create perfect municipalities in its place. It is the story of the expulsion of 40,000 inhabitants, racial exploitation and segregation, and the sanitation of the ‘filthiest and unhealthiest place on earth’.

And yet Lasso, now a professor of Latin American history in Colombia, has written a broader book than the narrow confines of her academic research dictate. Erased is in effect a justification of Latin America in the face of northern cultural and economic domination. Panamanians may now have forgotten the history and topography that predated the Zone, but so too have Latin Americans overlooked the fact that, in the 19th century, the region was at the forefront of modern republicanism. The way outsiders (and insiders) have characterized the region — as torn between barbarism and civilization — has reinforced Latin Americans’ sense of their countries as being second-rate, or places of thwarted ambition. The American short-story writer O. Henry did lasting damage when he heedlessly coined the term ‘banana republic’.

For all its academic credentials, Erased remains a personal work. While Lasso may have used this historical footnote to illustrate a wider point about the northern hemisphere’s notions of Latin American-ness, it is as much her own story. In her epilogue, she shows her hand when she returns to the old Canal Zone. ‘Neither the Zone nor I were the same… While the Zone was becoming part of Panamanian territory [a process that took place between 1979 and 2000], I was slowly becoming part of America.’

She wonders whether Theodore Roosevelt and William Lyman Phillips, both alumni of Harvard, would ‘appreciate the irony of a ‘“native” Panamanian woman writing a history of their canal in the same space where they used to study’. Perhaps the irony is another: that in order to understand Latin America, Lasso had to become ‘American’.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.