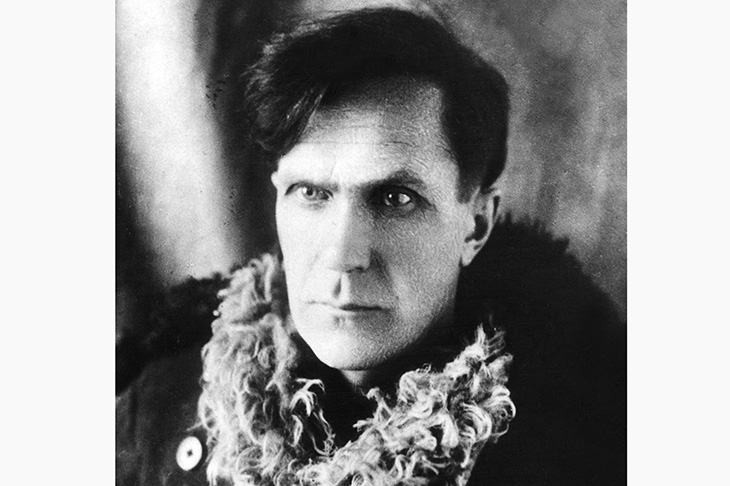

‘I consist of the shards into which the Republic of Kolyma shattered me,’ Varlam Shalamov once told a fellow gulag survivor. Sentenced to hard labor for Trotskyist activities, Shalamov spent 17 years in the gulag, primarily in Kolyma, located at the edge of the Arctic Circle, eight time zones east of Moscow and ‘one of the most uninhabitable places on earth’, according to the geopolitical journalist Tim Marshall.‘Instead of yesterday’s minus 40 it was only minus 25,’ Shalamov writes in one of the stories, ‘and the day seemed like summer.’

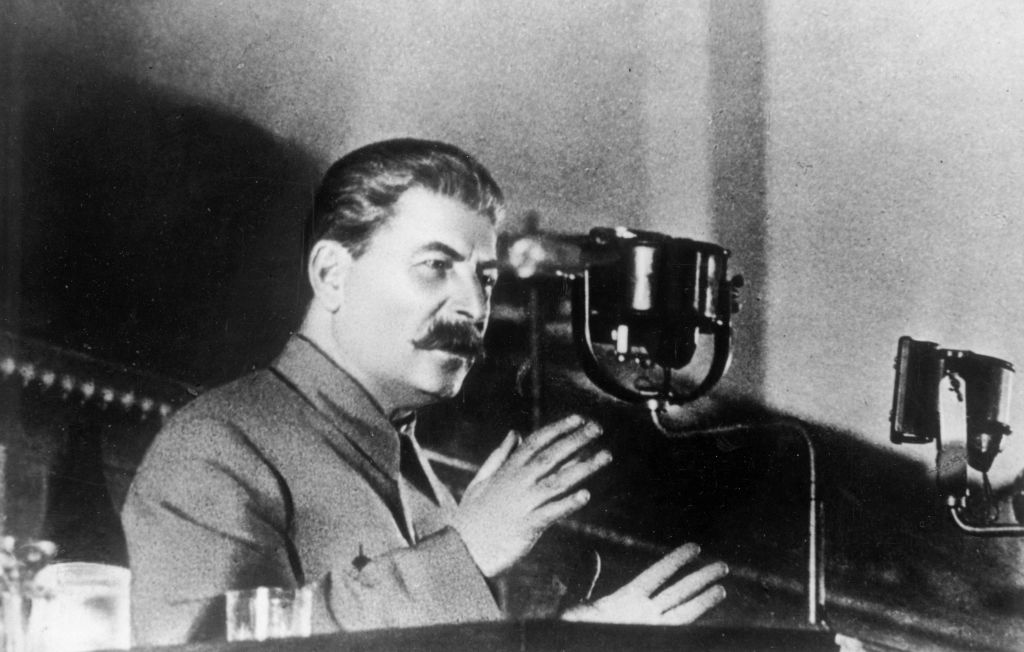

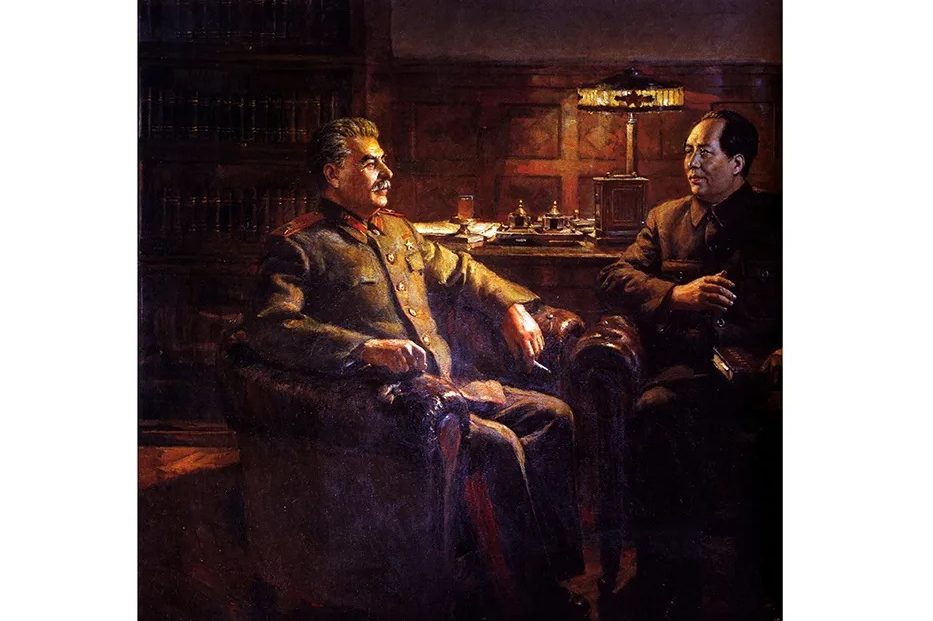

After Stalin’s death in 1953, Shalamov set out to chronicle life in the camps, producing 1,000 pages of what Masha Gessen, the Russian–American author and translator, has aptly called ‘the most harrowing and claustrophobic descriptions in the history of literature’. Unlike Solzhenitsyn, Shalamov, an avowed atheist, despite being the son of an Orthodox priest, refuses any redemptive narrative. Human beings live ‘by instinct’, he writes, ‘a feeling of self-preservation, on the same basis as a tree, a stone, an animal’.

The stories appeared piecemeal in the late 1960s in émigré journals and were passed around as samizdat in Russia. Although such distribution increased awareness of his work, Shalamov resented the loss of authorial control, as editors took liberties amending and reordering the text. He died in 1982, seven years before perestroika allowed for their official publication in Russia, which saw people lining up to buy copies.

Thanks to this new two-volume translation by Donald Rayfield, English speakers now have access to the six collections of stories in the Kolyma Tales in their entirety. (Rayfield has worked directly from the original manuscript, whereas the previous translator, John Glad, relied on edited émigré editions.) The translation shines particularly when rendering Shalamov’s more poetic language: ‘What do they use to sign death sentences?’ begins the story ‘Graphite’. ‘Indelible ink, Indian ink, ballpoint ink, or mordant red diluted with pure blood?’

The translation falters, however, when adding a layer of anti-Stalinist sentiment to the text. Scholars take issue, for example, with the choice of words in the last line of the opening story of Volume One, ‘Trampling the Snow’, considered a parable for the totality of the Tales. The story describes prisoners clearing a road through virgin snow as a metaphor for writing, with the black holes of footprints representing words on a blank page, and each prisoner required to forge his own path. The literal translation is: ‘And on the tractors and horses ride not writers, but readers.’ Instead of writers and readers, Rayfield gives us: ‘As for riding tractors or horses, that is the privilege of the bosses, not the underlings’ — losing the literary metaphor entirely and adding a political bent that is not in the original Russian. (Glad stays closer to the original in this instance, but adds his own flourish, using ‘authors and poets’ rather than ‘writers’.) Shalamov’s first-person accounts, which he described as ‘a slap in the face of Stalinism’, are damning enough.

The first part of this second volume, ‘Book Four: Sketches of the Criminal World’, features more essayistic pieces on the criminal codes that dictated the terms of the camps, where political prisoners were at the mercy of hardened criminals. Although it is undoubtedly important as a historical document, generalizations such as ‘all the gangsters are pederasts’, combined with the notoriously difficult task of translating slang, make this section less relatable to a contemporary western reader. Indeed, only two of the eight pieces made it into Penguin’s abridged collection.

The remainder of the book shares more of Shalamov’s first-person slice-of-life/hell sketches, with a Chekhovian artistry that led William Boyd to dub Shalamov ‘the new laureate of the gulag’. A Virgil of this icy underworld, Shalamov is at his most compelling when bearing witness. He spares no detail, describing the diagnosis of dysentery, corpses exhumed for their clothing and the hacked-off hands of fugitives used for fingerprint identification.

The only prose Shalamov composed during his detention was a dictionary of gangster terminology, which he says was ‘hard to write because my brain had become as rough as my hands and was bleeding as badly as they were. I had to bring the words back to life, to resurrect words that had left my life, as I believed, forever’. We are fortunate that he — who died deaf, nearly blind and institutionalized — not only survived his sentence but had the force to withstand the exorcism of the experience. ‘Graphite, which can record everything you’ve known and seen…is a greater miracle than diamonds,’ he wrote. ‘The trace left by a graphite pencil in the taiga is eternal.’

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.