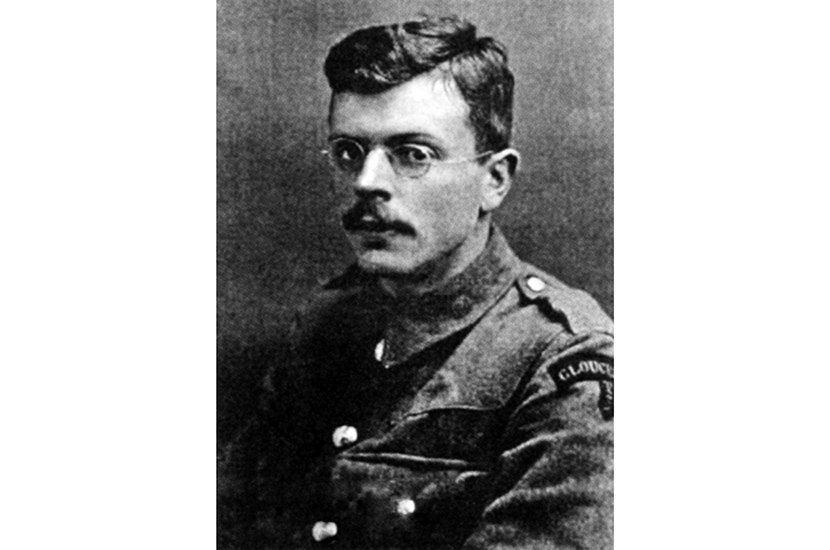

The poet and composer Ivor Gurney (1890-1937) is a classic but nevertheless shocking example of literary neglect. Although he brought out two respectfully received collections of war poetry during his lifetime, the idiosyncrasies of his style have prevented him from being widely recognized as the equal of his greatest contemporaries. His history of mental illness has further destabilized the reception of his work, not just by encouraging people to think of him as crazy, but by compounding practical difficulties surrounding its publication. In the 1980s Michael Hurd wrote a somewhat sketchy biography, and P.J. Kavanagh edited an expanded, but still partial, sample of his work. Only now has Kate Kennedy, in her enthralling, meticulously researched and deeply sympathetic life, finally done justice to his story.

Gurney was the son of a tailor in Gloucester (no kidding), but began to strain against his shopkeeper inheritance the moment he became a chorister at the cathedral school. In the process, he also acquired a reputation for eccentricity — one of his fellow pupils, William Bubb, remembered him as ‘always…batchy’ (a local colloquialism meaning something like ‘strange’). Right from the start, his personality mixed various kinds of oddity and ineptitude with bursts of self-confidence. Not entirely self-mockingly, when he first left the west of England and went to study for a degree at the Royal College of Music, he identified himself as a ‘young Genius’. ‘The sad fact is,’ he said, ‘that I do not know what it is to feel well, and what work I do has to be done in spasms very quickly over.’

Kennedy is careful not to sentimentalize these conflicts, or interpret them as evidence of a ‘fatal flaw’. But at the same time she realizes how especially vulnerable Gurney was, and how grievously he was disturbed when the outbreak of war interrupted his studies and turned his attention from ‘Beauty’ towards the trenches. At this stage his concentration was almost entirely on music rather than poetry — and the best of his early works, the ‘Five Elizabethan Songs’, for instance, show that his self-control was still intact. But once he was in uniform, and music-making became harder to organize, poetry began to flood into its place; and these poems, with their characteristic ellipses and syntactical contortions, are more obviously expressive of inner turmoil.

They also, and in a way that mirrors the contradictions in his personality, prove his hunger for a continuing sense of normalcy. Once in France, and encouraged partly by the example of Walt Whitman (who would eventually be joined by Gerard Manley Hopkins and Edward Thomas in a trinity of major influences), he began crowding his work with everyday details of trench life. This gives it a feeling of documentary realism that is unique in poetry of the first world war, and also an emphasis on the companionship of the fellow soldiers — he declined the opportunity to become an officer — who shared his conditions.

Overlying all this, there’s also an unusual emphasis on sound — not surprisingly, given his parallel life as a musician. In poem after poem, he tries to make sense of his experience by paying attention to the noises it contains: the barbarous racket of conflict itself and the occasionally sweet sounds of soldiers. At the end of what is probably his best known poem, ‘First Time In’, for instance, he listens to ‘a Welsh colony’ singing in ‘sandbag ditches’ and hears:

‘“David of the White Rock”, the “Slumber Song” so soft, and that

Beautiful tune to which roguish words by Welsh pit boys

Are sung — but never more beautiful than here under the guns’ noise.

Gurney was first wounded, then gassed, in the war, and the gassing in particular has often been given as the major reason why, after being invalided back to Blighty, his mind began to give way. Once again, Kennedy avoids giving a single explanation for what was evidently a complex process of decay, and as she follows Gurney through the course of a disappointed crush on one of his nurses, then the unhappy reconnection with his exceptionally difficult family, she demonstrates that the war was one reason among several for his eventual collapse.

For a time it seemed as though returning to the Royal College might save him; and while he didn’t manage to complete his degree there, he did at least catch the attention of one of his teachers, the composer Vaughan Williams, who along with the violinist Marion Scott and one or two other Gloucester friends did what they could to keep him on the level. But his family, and especially his deeply unlikable younger brother Ronald (who would later become the main obstacle to editors wanting to examine the whole range of Gurney’s manuscripts), stubbornly mishandled things. To put it bluntly, as Ronald often did, he simply wanted his brother off his hands, and in 1922 Gurney — now in a suicidal state of mind — was certified insane.

After a brief stay in an asylum close to home, Gurney was transferred to the City of London Insane Hospital in Dartford.The strangely brilliant poet was now patient number 6420. As Kennedy maps this dismal transformation, she writes with an exceptional mixture of imaginative sympathy and intelligence, but her pages make for harrowing reading. There was one doctor for every 450 patients at Dartford, almost no consideration given to how health might be improved, and a prevailing atmosphere of hopelessness. The particular tragedy of Gurney’s fate is that although clearly very ill, he generally retained his self-awareness, and was therefore permanently alert to his own misery. ‘He feels every thread of the suffering,’ his friend Marion Scott said.

For the first five years of his incarceration, and especially during 1925, he wrote and composed at a furious rate, producing poems which repeatedly test traditional forms. The great mass of this work has never seen the light of day, and if the passages quoted by Kennedy are anything to go by, it seems that Gurney often caught the same note of anguish we hear in some passages of The Waste Land — but re-scored in an English accent: ‘Not fashioned, but wrought iron/ With the cost of his own spirit in sparks giving.’ Does this mean that Gurney, who began life as a Georgian, turned into one of Britain’s missing modernists? It certainly sounds like it, but we can’t be sure until somebody edits and publishes a much larger collection of his work. Soon, please!

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.