Kenny Dorham was one of the jazz greats. The closest player in modern times to his intimate sound is probably Roy Hargrove, who, like Dorham, hailed from the Lone Star State. But despite all the accolades from the jazz cognoscenti, there is something plaintive about his career, down to the liner notes for his own albums. Indeed, right from the first sentence. Take the 1956 album Kenny Dorham and the Jazz Prophets on the ABC-Paramount label: “Kenny Dorham is one of those artists who have not as yet been accorded their deserved share of recognition.”

Two years later, in the notes to ’Round About Midnight at the Café Bohemia, Leonard Feather wrote, “In the course of introducing Kenny Dorham’s initial Blue Note LP, I felt obliged to point out that here was an artist who had been known too little for too long, whose fame had never quite caught up with his creative ability.” He added, “while not yet ready to knock Louis Armstrong off his pedestal” — ahem, who could? — “Kenny has certainly made substantial inroads in the area of public appreciation.”

It never quite panned out that way. All along, Dorham has been overshadowed by the likes of Miles Davis. By 1964, as mainstream jazz lost its audience, he had cut his last album as a leader. A longstanding heroin habit likely contributed to kidney failure, and he died in 1972.

Something of a Dorham revival, or at least appreciation, has occurred in recent years. Outfits such as Music Matters and Acoustic Sounds remastered some of his most important work for Blue Note records, where he cut five albums as a leader, including ’Round About Midnight, which Ron Rambach, the founder of Music Matters and a walking encyclopedia of jazz recordings, deems one of the greatest Blue Note LPs ever recorded. Dorham also made a number of other significant LPs — though the Jazz Prophets has not been reissued, it has been a coveted album among collectors.

His lucid prowess actually sounds more contemporary than the discordant jazz fusion that Miles Davis and others embraced in the late 1960s. “They holler, ‘Freedom! Freedom! Avant-garde!’ That’s fine,” Dorham wrote in 1970 in an autobiographical note in DownBeat magazine. But that wasn’t his bag. He didn’t have miles to go. There’s nothing stale or musty about his precise, clean and vivid playing. On the fiftieth anniversary of his death, it’s well worth revisiting his remarkable career.

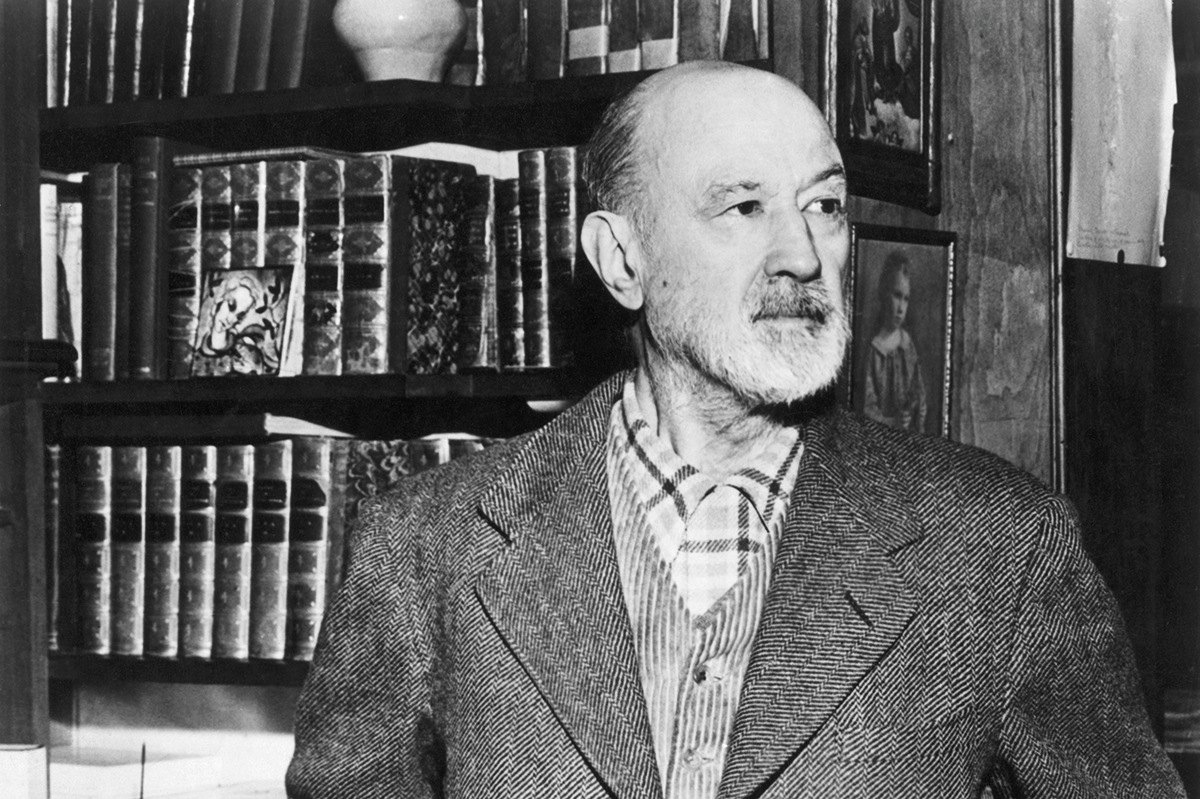

McKinley Howard Dorham — who was born into a sharecropper family on August 30, 1924 in Fairfield, Texas — did not have an exuberant personality like Armstrong or a brooding one like Miles Davis. He was softspoken, careful and deliberate, thoughtful and understated, as you can hear as he introduces the tunes to the audience on the live recording ’Round About Midnight. He fell somewhere between two stools, melding traditional bravura style with a more confiding tone.

Like many other jazz stars, he picked up trumpet in his teens and jammed in high school with talented peers. He studied music at Wiley College, where he played in a band that included the pianist “Wild” Bill Davis. Next came a stint in the Army during World War Two before he headed to the big city. In New York, he honed his bebop and swing skills, playing with Mercer Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Billy Eckstine and Lionel Hampton. In 1949 he appeared with Charlie Parker at the Paris Jazz Festival, and in the mid-1950s he performed regularly with Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers.

One of his earliest solo albums is the fabled Afro-Cuban, which appeared on the Blue Note label in 1955. It was far ahead of the curve in integrating Latin rhythms into jazz. I’ve always been a sucker for Latin jazz, which has an infectious bounce to it that none but the most acidulated listener can resist. On the song “Afrodisia,” powered from behind by Art Blakey’s drumming, Dorham, together with the saxophonist Cecil Payne and trombonist J.J. Johnson, offers a relaxed swinging interpretation.

The Latin flavor resurfaces on the 1959 album Quiet Kenny on the New Jazz label on the opening song “Lotus Blossom.” At the same time, he displays his seamless and flowing quality on the tune “My Ideal.” The Latin-based theme would emerge once more on his 1962 album Matador and its title cut. Once again, Dorham displays an enviable rhythmic swagger on his opening solo, one that has him playing against the beat with a taste of funk. The same goes for Una Mas, which appeared in 1963 and which is guaranteed to put a grin on your face.

His final album as a leader, 1964’s Trompeta Toccata, features Dorham at his boldest on the opening toccata as he stretches out into the higher regions of the trumpet and engages in flutter-tonguing as well. Could quiet Kenny make a big impact? You’re darn tootin’.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2022 World edition.