The rebranding of John Browne has been a long and, to those of us living overseas, instructive affair. Readers will recall the unedifying circumstances leading to his dismissal from BP 10 years ago, when the country’s usual gang of disagreeable and unkindly figures such as Paul Dacre and Tom Bower were snapping busily at his heels. Much has happened since.

In the classic style of the British establishment, his disgrace has been followed by a steady stalactitic drip of preferments and praise, committees and chairs and board memberships, much aided by quires of unctuous journalism, most tending to focus on the impeccable taste and artistic judgment (not to say financial savvy) with which he has furnished and stocked his digs in the fashionable quarters of London and Venice.

Now, after an inevitable confessional book about the benefits of ‘coming out’ in the boardroom (which Apple’s Tim Cook seems to have managed with rather less fanfare) and a pair of politely received business advice manuals, we have this very much more significant and satisfactory volume, which offers up an impressively repurposed John Browne. Here he is as public intellectual and national guidance counsellor, bent on directing the country out of its current post-imperial innovative quagmire and towards the sunlit uplands of a high-technology utopia, and presenting the very best of what he believes tomorrow’s world has to offer to us all.

Though Browne is a corporate man to his very soul — variously described by former BP courtiers as organized, impeccable, driven, remote, aloof, and fond of quoting Intel’s Andy Grove’s remark that ‘only the paranoid survive’ — he likes to say that he is, by intellectual preference, an engineer. He tells us that he became one in large part out of reverence for his adored mother — a Transylvanian Jew and survivor of Auschwitz — and her imperturbable optimism. So ‘when it came to earning a living I wanted to solve problems that others had not yet even conceived of’, he writes here, and engineering was his chosen means of doing so.

That period of his professional life is now over; no longer enjoying the sheet-anchor of BP, for whom he worked for all of his career, nor of his mother, who died in 2000, he has decided here to delve into the minds of others who are themselves busily solving technical problems ‘not even conceived of’, and who thereby are maybe bettering the world. This book, an engaging and stimulating trek through their thinking, is the result.

In Britain it is widely held that engineering has lately had something of a bad rap, with today’s legatees of such technological giants as Watt, Whitworth, Maudslay and Brunel a handful of plucky but diminished figures, such as Clive Sinclair and James Dyson. Wisely, Browne — whose boardroom Rolodex must have been immeasurably vast — looks beyond his homeland, and such people, to find those who are really sharpening the cutting edges of the various disciplines that engage him. He looks far, but, as I will suggest later, maybe not far enough.

He organizes the book in an engaging, though initially somewhat confusing, way. (I feel much the same way about his rather eccentrically ordered title.) Some of the 10 chapters are straightforward enough: ‘Build’, for example, is as you would expect about new developments in construction technology and city planning (placed briefly in historical context, as all the chapter are: here he begins with the Mayans and their use of hydraulic cement).

And Browne or his research colleague Ben Martynoga (a neuroscientist-turned-science-writer of evident brilliance) talks to, or quotes from, the words of leaders in the field — Richard Rogers, Frank Gehry and Norman Foster being for this chapter the all-too-obvious suspects. But, refreshingly, we are also introduced to new and lesser known figures: thinkers such as Tristram Carfrae, of Arup, who has much to say about modern architects’ imaginative future uses for computers, and the environmentalist Peter Head (who leads two bodies with formidable names: the Ecological Sequestration Trust and the Resilience Brokers Program). He tells among other things of China’s so-called ‘sponge cities’, which use lots of new-fangled porous materials and plants to create ‘pleasant and varied urban environments’, sorely wanting in modern China.

Another chapter, ‘Move’, is similarly enjoyable with its no-frills disquisition about new thinking in matters of mobility. One can weary a little at Browne’s habit of frequently reminding us of his privileged life (‘I was fortunate enough to travel on Concorde many times’ he tells us. And, in ‘Build’: ‘When renovating my home in London I tried to embed as much automation and intelligence within it as I could… There are no unnecessary switches, locks or visible consumer electronics.’). But disregarding the self-regarding, the substance of ‘Move’ is most rewarding: we learn, for instance, of new developments in battery research for use in aircraft (with lightweight batteries that can turn arrays of small propellers for high-altitude cruising), and hydrogen-based engines for cars that will soon, Browne suspects, be populating the roads of an England that currently has just one hydrogen fuel pump (though he sagely notes that back in 1919 there was only one pump too, then dispensing petrol).

I would have hoped, though, for rather more substance in ‘Energize’, the chapter that, considering Browne’s glittering (if attenuated) career with BP, would have played to his ideatic strengths. He has no hesitation in confessing his unwavering commitment to his early professional passion:

‘I entered [the energy industry] to solve problems rather than to create them — it is a decision that I have never once regretted or felt ashamed of, because I believe the industry can, and will, be a part of the solution to its own problems.’

And yet, despite interviewing thought leaders in the field — at MIT, at Culham, at photovoltaic laboratories in Oxford, and at the Vatican no less, where the Pope had staged a crisis conference — he seems somewhat equivocal: we are bound to use more energy, we need to protect the environment, ‘the amount of hydrocarbons in the mix will depend on effective incentives to reduce the use of carbon…’ This is a disappointing stream of platitudes from a man whose lifeblood was crude oil and who on leaving BP spent years as head of a fracking conglomerate. I just wish he could have been more trenchant and radical in expressing an energy vision for the future.

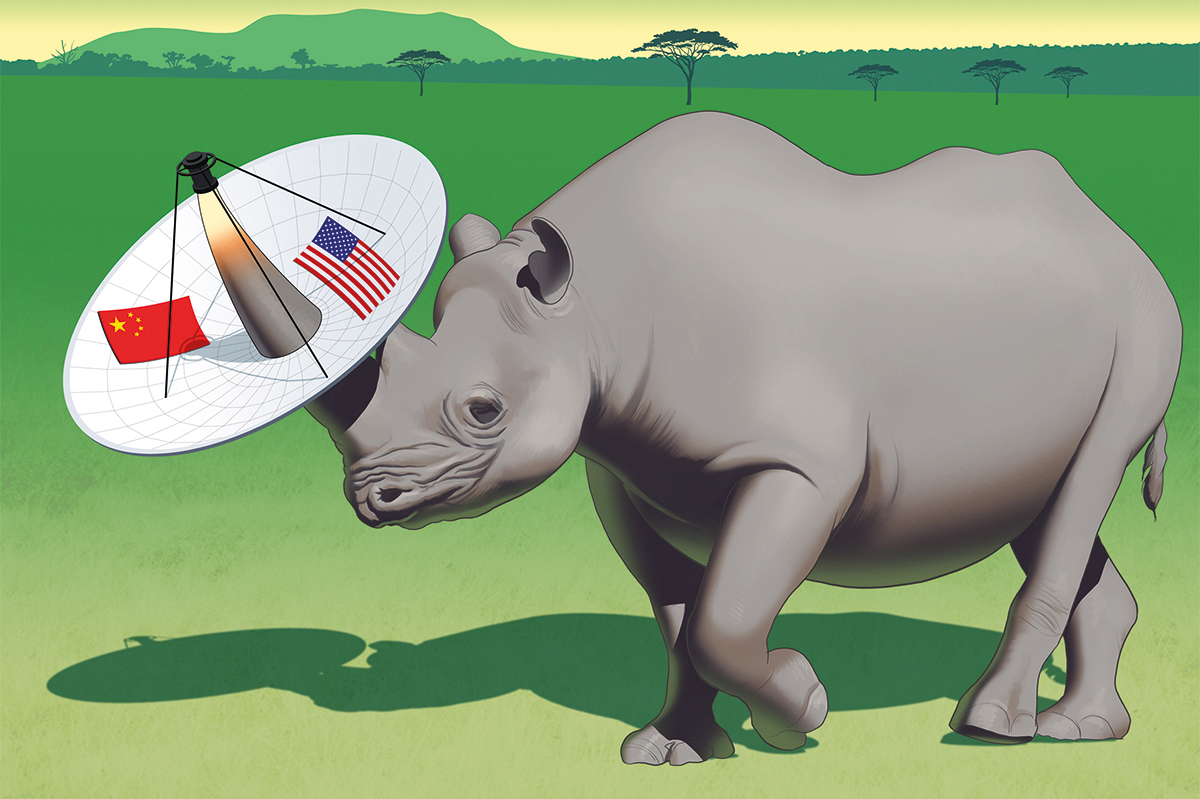

But the most serious shortcoming of this otherwise worthy and intelligent book is the national origins of the scores of men and women whose views underpin its main thesis. Almost all of them are white, and western. Asia scarcely merits a mention. Browne seems to have been blissfully unaware of, or else mulishly unwilling to tell us, what Chinese scientists and engineers in particular are planning or pondering about the future. And considering that China is on the verge of running the world, his decision is an omission of some importance.

But he does mention Joseph Needham, the Cambridge academic who famously declared in the 1950s that China had a vastly long history of technological and engineering creativity, and who chronicled in his monumental Science and Civilization in China how the Chinese had pioneered world-changing inventions from the stirrup to printing, and the compass to gunpowder. And so Browne must have been aware that during the past two centuries of domestic turmoil, such innovative progress had stilled — only to resume with a vengeance in more recent times. And has accelerated almost exponentially in the past 20 years.

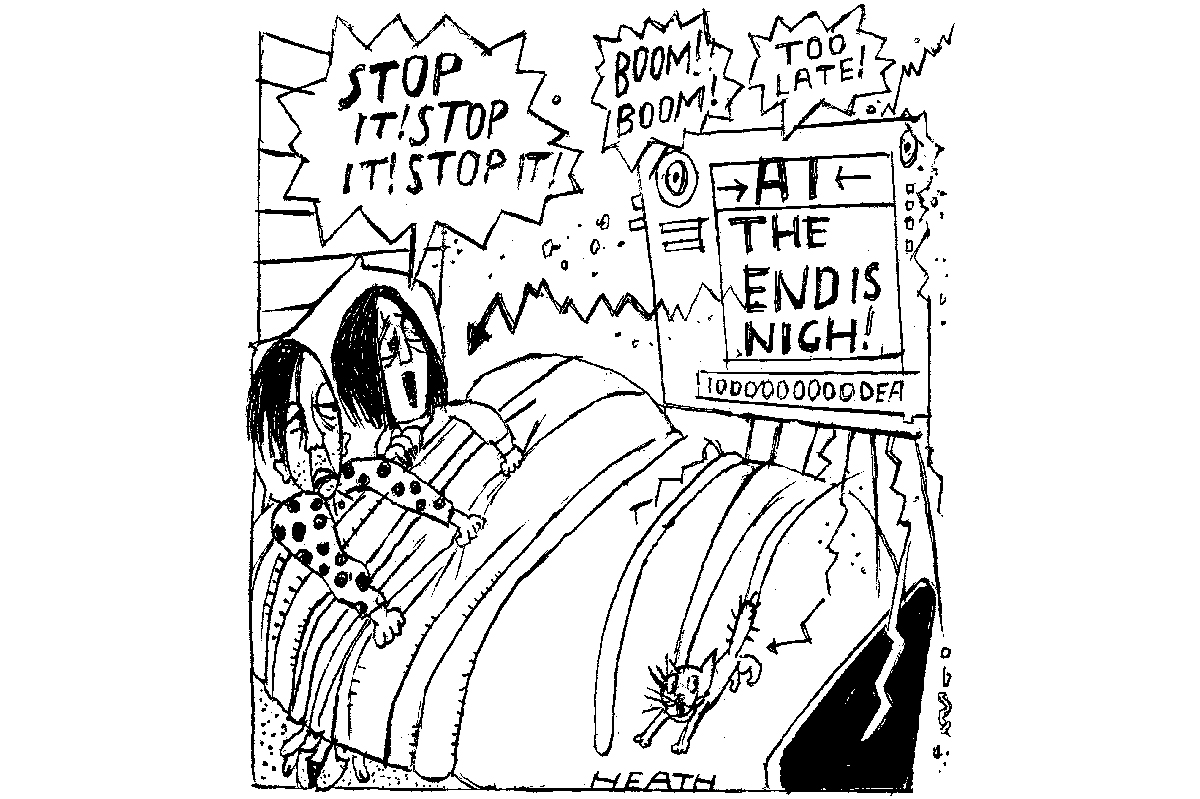

Today, China handily outstrips America in the total number of patent applications; and Japan and South Korea follow closely behind. (Britain is effectively nowhere in the field.) Innovation — buoyed, of course, by a rigorous system of education — is now central to the Asian regional psyche. And yet precious little evidence of the work of any Chinese, Korean or Japanese engineer makes it into Make, Think, Imagine. This seems to me a near-fatal flaw. Perhaps Browne should get out more, and we should wait breathlessly for him to write, as elegantly as he has done here, a second volume. Only perhaps rebrand this one more properly: Imagine, Think, Make.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.