Pop music is tribalist by nature and divisive by desire. It was always the Beatles or the Stones, mods or rockers, burn the Beatles’ records or ‘hang the DJ’ and, most important of all, Bob Marley or Big Youth? (The answer is Big Youth.)

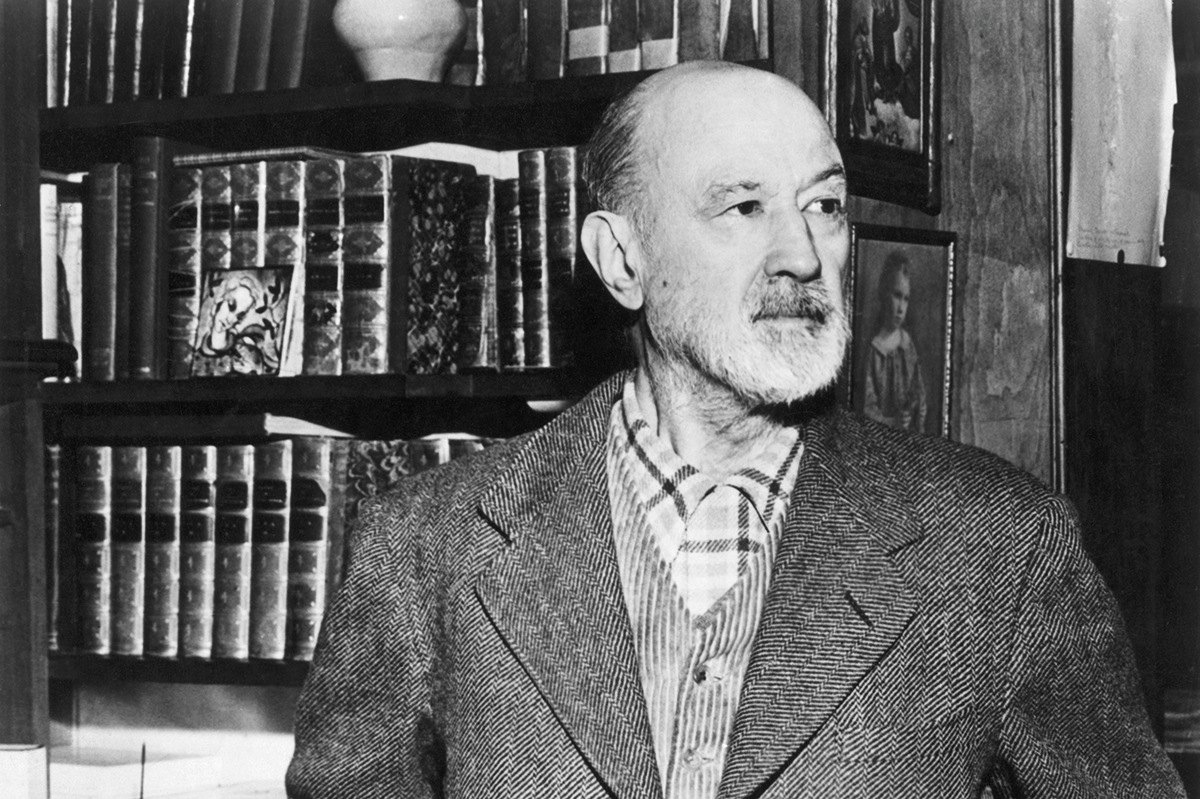

Only one man transcended this nonsense: Frederick Nathaniel ‘Toots’ Hibbert. Anyone who has heard Toots but doesn’t dig his mighty soul skank should be cast into the wilderness for 40 days and 40 nights of good, hard thinking. Toots died on September 11 in his native Jamaica. He was 77, allegedly the victim of complications from COVID-19. The man may have gone, but his vibrations will live on as long as mankind has ears to listen and feet to dance.

Toots & the Maytals were shockingly early for the post-war pop boom: fully formed in 1962, the year of Jamaica’s independence. In the interregnum between Elvis going into the Army and the Beatles going to EMI, British pop-pickers were held hostage by Cliff Richard, a feeble Elvis impersonator, and the homely yodeler Frank Ifield. America had country from Nashville and Bossa Nova from Brazil. But Kingston, Jamaica had the ska of Clement ‘Sir Coxsone’ Dodd, Leslie Kong and Prince Buster.

The pairing of these maverick producers with Toots’s songwriting and multi-instrumental prowess led to a visionary run of mid-Sixties to early-Seventies classics: ‘The Sixth And Seventh Books Of Moses’ (about Obeah, the Rastafarian spiritual healing belief), ‘Do The Reggae’ (in which Toots records a dancehall floor-filler and names a genre, no less), ‘Sweet and Dandy’, ‘Monkey Man’ (covered by the Specials in the ska revival), and the astonishing ‘Pressure Drop’, a song so bulletproof that even the Clash couldn’t ruin it. (Which is more than can be said for their version of Junior Murvin’s luminescent masterpiece ‘Police and Thieves’, which the Westway Wonders managed to convert into a masterclass in musical hod-carrying.)

Toots, like all the best rock ’n’ rollers, managed to get busted for weed and ended up in the pen. It all worked out: in 1968, he had a massive Jamaican hit with the stone classic ‘54-46 Was My Number’ (the number of his prison ID). The song went deep into the popular psyche and has been covered by the great and the good: Aswad, Buju Banton, Yellowman and the master, Vanilla Ice.

By 1972, reggae, the music that Toots named, was breaking out of Jamaica via the rude-boy noir classic (and Jimmy Cliff vehicle) The Harder They Come. Its hard-bitten gangster cool and stellar soundtrack had a big impact on the Clockwork Orange kids of Britain. As good as the movie is, Toots & the Maytals steal a scene by playing a studio version of ‘Sweet and Dandy’ to an audience of dreads and a genuinely awestruck Jimmy Cliff.

There is a school of thought that claims that Toots was pipped to the title of World King of Reggae by Bob Marley & the Wailers. But that is to miss the point. Island Records’ Chris Blackwell was behind the scenes on both the Wailers’ Catch A Fire (1973) and Toots’s contemporaneous and definitive statement, Funky Kingston. Bob’s album sold more and launched him toward the myth he remains today. Still, unarguably great as Catch A Fire is, Funky Kingston is greater: full of super tight ruff ‘n’ tuff rock-steady rhythms with Toots, a Caribbean Otis Redding or Wilson Pickett, giving a throat-shredding soul holler. (There are two versions of Funky Kingston. Try and get the Jamaican one: the 1975 one is essentially a compilation.)

Toots was semi-retired by the early Eighties and teaching. Indefatigable, in 1988 he won a Grammy for the Toots in Memphis album. This was when Toots became a much sought-after collaborator. You wanted to work with Toots? Get in line behind Willie Nelson, Bonnie Raitt and serial reggae-botherer Eric Clapton.

In 2013 Toots was seriously injured by a drunken bottle-thrower at a gig in Virginia. The assailant threw the bottle at the drummer and Toots stepped in to take the impact, copping a serious head injury. Toots asked the judge to be lenient.

In his last interview, given to promote the album Got To Be Tough, Toots called his songs his ‘lucky charms’. He was right. Songwriters often say that when songs go out into the world, they become everyone’s. I say, go out and pull a Toots & the Maytals classic out of the air. Listen to ‘Bam Bam’, ‘Funky Kingston’, ‘Pressure Drop’, ‘Pomps And Pride’, and for as long as they last, you too will be the luckiest person alive

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 2020 US edition.