Catherine Called Birdy is written and directed by Lena Dunham and it’s a medieval comedy about a fourteen-year-old girl resisting her father’s attempts to marry her off while yearning to do all the things women aren’t allowed to do. (She would especially like to attend a hanging, for example. And also “laugh very loud.”) It most put me in mind of Monty Python and the Holy Grail, as it has that spirit, but it does not share that timeless brilliance. It’s fun, and endearing, and the patriarchy gets a good kicking which, as you know, is my favorite thing. But it feels like one joke or sketch that’s been dragged out for nearly two hours. It’s fine, yet forgettably so.

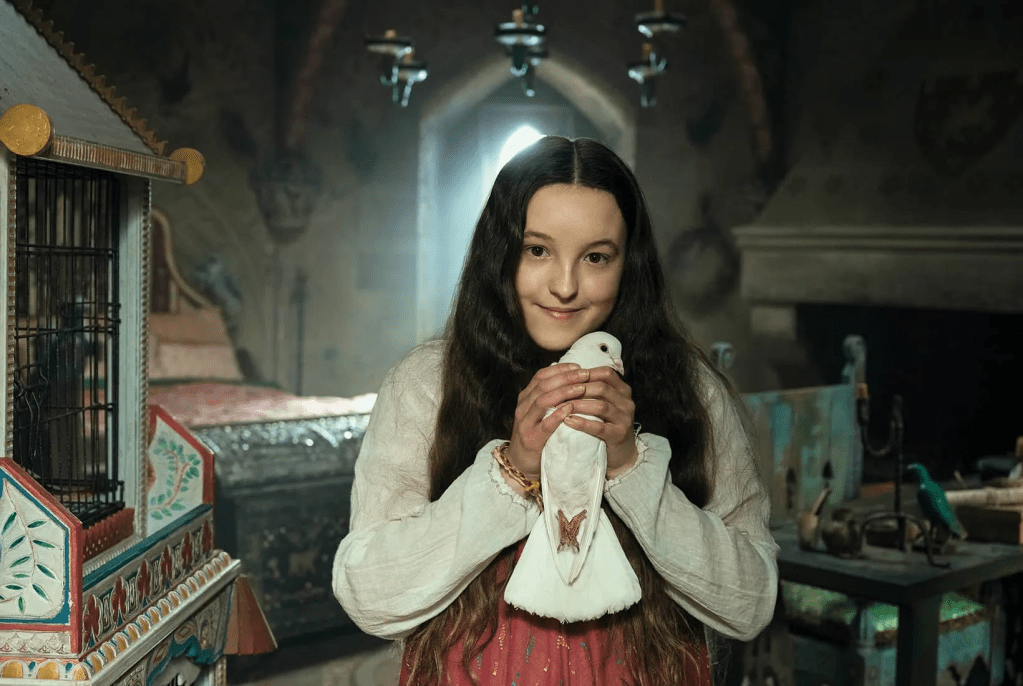

Dunham, who created the HBO hit comedy Girls, which is pure genius, adapted this from the novel by Karen Cushman. It’s a YA novel, which I only realized latterly, but that makes sense, as the film seems to be aimed at the teenage market, and the fact is I may just be too old. (I can only apologize.) It stars Bella Ramsey, known from Game of Thrones, as Lady Catherine, who is also called Birdy as she keeps birds as pets. It’s the thirteenth century and Catherine lives in “the village of Stonebridge in the shire of Lincoln in the country of England” and has passions that include “avoiding chores, critiquing my father’s horrible swordplay and listening through doors I should not listen though.” We first make her acquaintance as she’s participating in a mud fight with her friend, Perkin (Michael Woolfitt), the goat boy, and there is flatulence, not for the last time. It does have a terrific cast. Her nursemaid, Morwenna, is played by (for some reason) a deeply Scottish Lesley Sharpe. Her father, Lord Rollo, is played by Andrew Scott, and Billie Piper is her mother, Lady Aislinn. Piper doesn’t get to do much — Lady Aislinn is the most underwritten character — but even Piper not doing much is better than no Piper at all. (I love Billie Piper. Top tip: if you’ve yet to do so, watch her TV series I Hate Suzie.)

Lord Rollo, meanwhile, has frittered away the family money and needs Catherine to marry someone rich. She has no choice in the matter. “You are my only daughter. If I say you will be married, then married you will be.” But Catherine is spirited and adventurous and smart etc, etc., and devises increasingly ingenious ways to repel her suitors. She repels one (Russell Brand, suddenly popping up) when she meets him in the fields. He doesn’t know who she is, so she tells him that Lady Catherine is a vile creature with a third ear on the back of her neck, and he’s off. This scenario is repeated over and over, while she pines for her mother’s younger brother, Uncle George (Joe Alwyn), which is weird. But, as she notes, he does have excellent teeth.

There are some decent moments, such as when Lord Rollo, apologizing to one suitor for Lady Catherine being in a grump, says maybe it’s the pox, “but not the big pox. Only the small pox!” I laughed. But otherwise it’s not surreal enough to be marvelously silly and it’s not precise, bold or sophisticated enough to be eviscerating satire. It’s tame, often over-acted — but not by Piper! — while Dunham’s direction is solid without being inventive. Freedom is represented by light suddenly streaming into windows or birds being released from their cages. Each character is introduced by amusing intertitles, which we have seen done many times before and no longer feels mischievous. Despite all the rebellion on view, this gives it a listless, plodding quality. Alternatively, I could just be too old, too tired. Once more, I apologize.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.