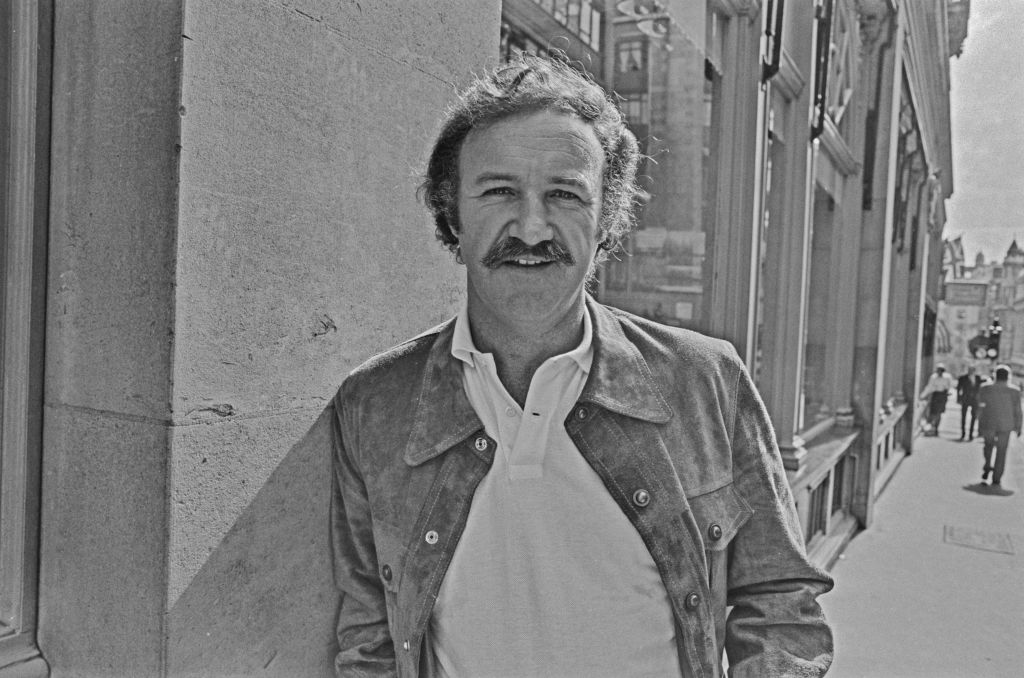

The screen begins on black; a slow reverse zoom reveals that we’re looking at a laptop screen during a Zoom meeting. We think we’re watching a film reflecting the realities of Covid. But it’s 2016, and the black screen in the middle (reading “instructor” in the lower right-hand corner) belongs to our protagonist, Charlie (Brendan Fraser). He’s teaching an online English class, going through the motions of a job that means very little to him. His world is dark and painful; he doesn’t want to let anyone in. After he logs off, we see his enormous body masturbating to gay porn.

His orgasm triggers a heart attack that feels like the punchline to a cruel joke, but it plays as anything but that. For the next two hours, we’re going to bear witness to his world, and it’s supposed to feel like a violation.

As soon as Darren Aronofsky announced The Whale, his superb new adaptation of Samuel D. Hunter’s play about the slow suicide of a morbidly obese man, some cultural commentators on Twitter erupted in an entirely predictable manner. What right, these enlightened guardians asked, did bad boy Aronofsky have to portray struggles he knew nothing about? Surely this hack would exploit and mock the protagonist’s pain. One critic even went so far as to proudly announce they would not see the film.

Not only were these statements in bad faith, they evinced a curious misunderstanding of Aronofsky’s MO. For almost a quarter-century, Aronofsky has been making stylistically extreme portraits of human agony that force the viewer to approximate the characters’ subjective experiences, from mental illness in pursuit of a scientific (Pi) or artistic (Black Swan) goal to the ravages of drug addiction (Requiem for a Dream) and the toll of athletic entertainment (The Wrestler). Even his grandiose climate change metaphors (Noah and Mother!, his greatest film) refuse to put us at a distance from his characters. Just as Todd Solondz and Alexander Payne are wrongly accused of smugly mocking their characters, Aronofsky gets targeted for alleged misery tourism. If you accept both premises, it feels like the only way to approach any painful, serious subject is through respectful, Oscar-friendly distance — in other words, in as boring a manner as possible.

The good news is that Aronofsky has gone and made another uncompromising film, anchored by Brendan Fraser’s extraordinary performance as Charlie, the English teacher whose depression and weight have spiraled out of control, feeding each other and making extrication impossible.

The only one allowed into Charlie’s cluttered private space is his nurse Liz (Hong Chau) who cares for him enough to tell him his lifestyle is pushing him to the verge of death, all the while bringing him high-calorie foods she’s clearly learned long ago not to deny him. In an excellent scene, Aronofsky holds our empathy and attention as Charlie devours a greasy sandwich while Liz washes dishes off-screen. The 1.33:1 frame makes Charlie feel boxed in, even before he begins to choke.

Liz is only a few feet from Charlie, but feels impossibly far away until she re-enters the picture to perform the Heimlich maneuver (the sink water running all the while). This and other moments recall the vile TLC reality show My 600 Lb. Life, which holds up poor, desperate people as objects of ridicule, offering them extra money if they appear nude on camera. But here, we’re supposed to understand these moments belong to Charlie — we bear witness, and it’s deliberately queasy.

Gradually, more characters enter the film as Charlie resists going to the hospital to save his life (he has no health insurance): his estranged daughter Ellie (Sadie Sink), his ex-wife (Samantha Morton), and a young Christian missionary (Ty Simpkins) who believes he can offer spiritual guidance in Charlie’s last week of life. It becomes clear how Charlie wound up in this state: a decade ago, when he was still teaching classes in person, he abandoned his family for a male student. Eventually, his partner developed an eating disorder, and haunted by his own Christian guilt, jumped off a bridge, sending Charlie into a depression self-medicated by binge-eating (the poetic opposite of his partner’s forced starvation).

Ellie understandably loathes her father, but because he is unable to see anything but the perfect memory he walked out on ten years ago, he accepts her torrent of verbal abuse and taunting with delusional zeal.

Here, the film finds its true purpose, and it’s in the process of belief. Charlie has rejected the church that he blames for his boyfriend’s death, but maintains his belief in Ellie for her “honesty,” even as she accepts his offer to write her high school English paper. There’s no attempt to stand in for the worst excesses of zoomers or millennials; she’s just a thoroughly detestable character, perhaps the most odious screen teen since Daryl Sabara in World’s Greatest Dad.

As she begins to interact with Simpkins’s preacher, the dynamic between them and Charlie recalls Richard Loncraine and Dennis Potter’s masterpiece Brimstone and Treacle, which suggested that only the delusional could hold faith and the only miracles came accidentally — an unintended side effect of great evil.

But Aronofsky isn’t as cynical as Potter. As Charlie’s bottoming out begins to resemble the darkest scenes of the director’s career, his empathy blends with our own. Aronofsky simply cares too much to turn us into gawking spectators of what Roxane Gay described (wrong-headedly) as a “cruel spectacle.”