There is a culty YouTube video shot three years ago on the laptop camera of Ruben Ostlund. It shows the film director listening live as the nominations for the Academy Awards are announced from Los Angeles. The tension mounts as they approach the foreign film category. Alas, Force Majeure from Sweden isn’t nominated. Ostlund disappears off screen to sob and mewl. This year, there was a sequel to the video, but with a happier ending: the director’s latest film The Square was nominated for an Oscar.

These mini-movies, like the rest of Ostlund’s oeuvre, are funny but subtly savage. He is a provocateur who trades in discomfort. You watch with your toes knotted. In Play (2011) a group of black teenagers inflict psychological torment on two white kids and (to complicate things) an Asian. In Force Majeure (2014) a man on a skiing holiday flees an avalanche, shamefully abandoning his family and earning the vituperation of his wife. And now there’s The Square. It tells of Christian, the tall, dapper and handsome Danish director of a museum of contemporary art in Stockholm (played by Claes Bang), who helps thwart a mugging, only to discover that he’s been pickpocketed. His quest to retrieve his mobile phone, which lures him into a world of migrants and beggars, strips away his self-image of liberal civility.

The Square did not win in Los Angeles a fortnight ago, but it is well worth catching. The title alludes to an art work that issues a challenge to gallery-goers and, by implication, the film’s audience. Anyone standing within its perimeter enters into a social contract to interact with whoever else they find there.

‘I compare it to a pedestrian crossing,’ says Ostlund. ‘It’s a new way of trying to remind us all of certain humanistic values.’ Put like that it sounds wearyingly worthy. The film is anything but. A rib-jabbing satire on western decency, its first germ was an unsuccessful bank robbery that took place in Sweden in 2006. Ostlund was fascinated by the prevalence of the so-called bystander effect, which inhibits onlookers from reacting to such scenarios if others are present: no one intervened, even to help children in the path of danger. He reconstructed it in an 11-minute one-take film called Incident by a Bank which won the short film award at the Berlinale in 2010 and can be viewed on Amazon Prime.

‘When you read the court files, the bystander effect was super-strong. People didn’t interact even though they were very close. Then my father told this story about how when he was six he got his address tag tied round his neck and they sent him out to play. So the attitude changed. At the same time criminality had actually decreased in Swedish society. It was our paranoia that had increased.’

The Square opens with a journalist (played by Elisabeth Moss) challenging Christian in an interview to defend some art gobbledygook found on the museum’s website. Ostlund lifted the execrable text from an email sent by a fine art professor at the University of Gothenburg, where Ostlund also teaches. ‘I thought it was hilarious. I have still not asked for permission. It’s pointing out a certain kind of art movement that Goldsmiths was quite responsible for. It’s like a wet blanket over students at art schools. It’s taking away so much energy.’ Much of the art discreetly parodies the stylised debris one encounters in such museums. And a puffed-up artist called Julian, played by Dominic West, is specifically modelled on Julian Schnabel.

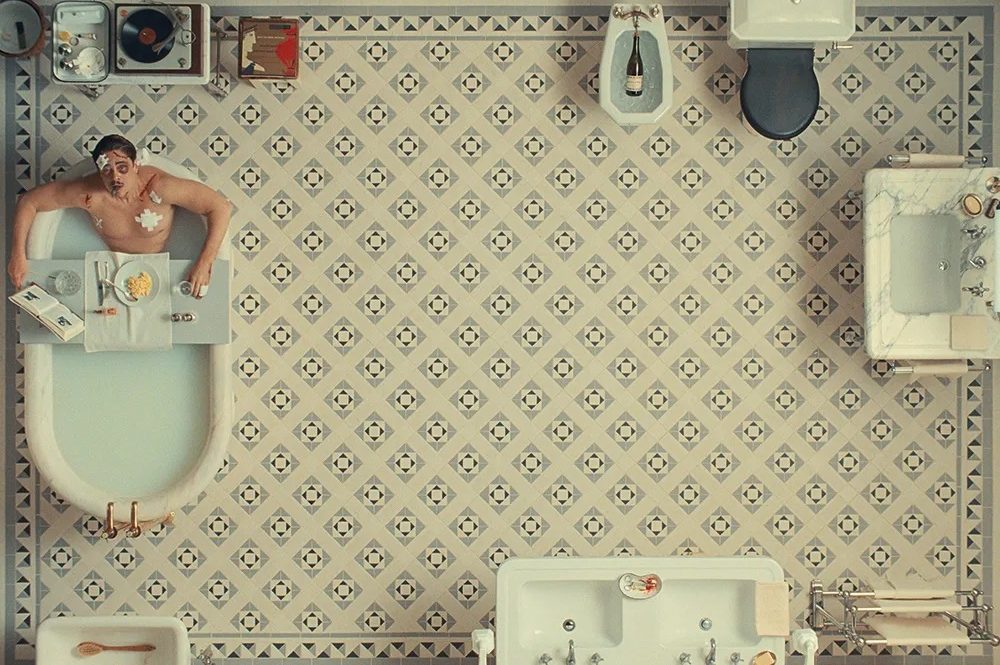

A scene from The Square

Christian later sleeps with the journalist — the sex is shot from frank, participatory angles — and, in an excruciating scene, refuses to let her dispose of his condom out of an inchoate fear that she will steal his sperm. Like much in the film this incident was lifted from actual experience, not Ostlund’s own but a friend’s — although he admits that Christian, who practises spontaneity in the mirror, is partly a challenging self-portrait. (They both have floppy hair.)

The burglary sting that opens the film was based on a scenario in which Ostlund was dragged into defending a woman under threat from a man in the street. Like Christian, he enjoyed an intense burst of adrenaline. ‘I was feeling really really proud. Then I went to my office and saw this man sitting on the bench crying and the woman was trying to comfort him. It was something so much more complex.’

In order to promote the concept of the square, the museum hires a pair of fatuous publicists who recommend an attention-seeking video in which a blonde child is blown up. A YouTube sensation becomes that weird marketing oxymoron, a disastrous success. ‘The provocation is aiming to show how the media is falling straight into the trap of people doing cynical things. The absurdity that we have a humanistic art piece that we are promoting by doing a completely cynical video.’ Ostlund stopped short of having the words ‘allahu akbar’ accompany the explosion. ‘I don’t want to give oxygen to a certain kind of conflict.’

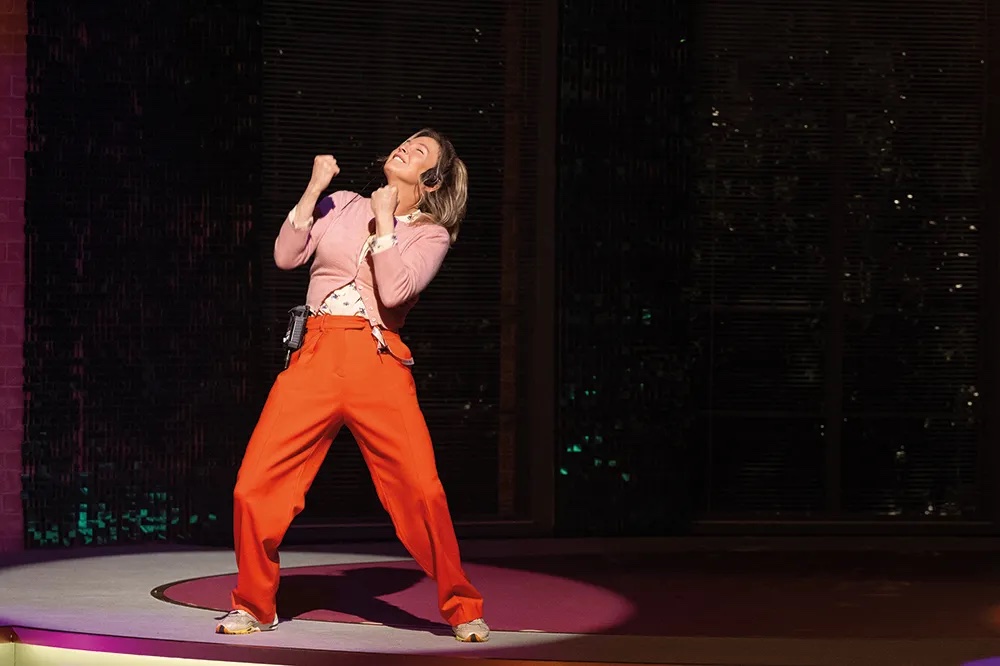

The message of Ostlund’s films is that human nature is conditioned by unconscious impulses — tribal, territorial, primordial — that go far deeper than learned social rubrics. This is most overt in the scene featured on the poster advertising the film, which shows a man stripped to the waist moving among swankily dressed museum donors at a gala dinner. He is a performance artist called Oleg who imitates primate behaviour (played by Terry Notary, who has monkey credits in Kong: Skull Island and the Planet of the Apes films). Having driven off the alpha male played by Dominic West, he embarks on a rape before the men in black tie ferociously restrain him.

‘I wanted this fancy audience to have to deal with him,’ says Ostlund. ‘Terry was so good that when he came out after a screening in Austin at the Fantastic Fest the audience was really really scared. A pregnant woman told the media that she didn’t trust the festival to take care of her security.’ This is who we really are, Ostlund’s films say — Moss’s character even keeps a pet chimp. In Force Majeure the protagonist’s personality crumples when he realises he’s simply not who he believes he is. Christian’s odyssey is a little less traumatic, and he is no less comic than anyone else in a film that targets society rather than individuals.

‘I think all the characters are more or less making a fool of themselves,’ says Ostlund. ‘We have to dare to look at ourselves and see how ridiculous we sometimes are.’