The period of the First World War was a golden age for the spy novel. There’s nothing like a really cataclysmic global conflict to stir any halfway attentive author.

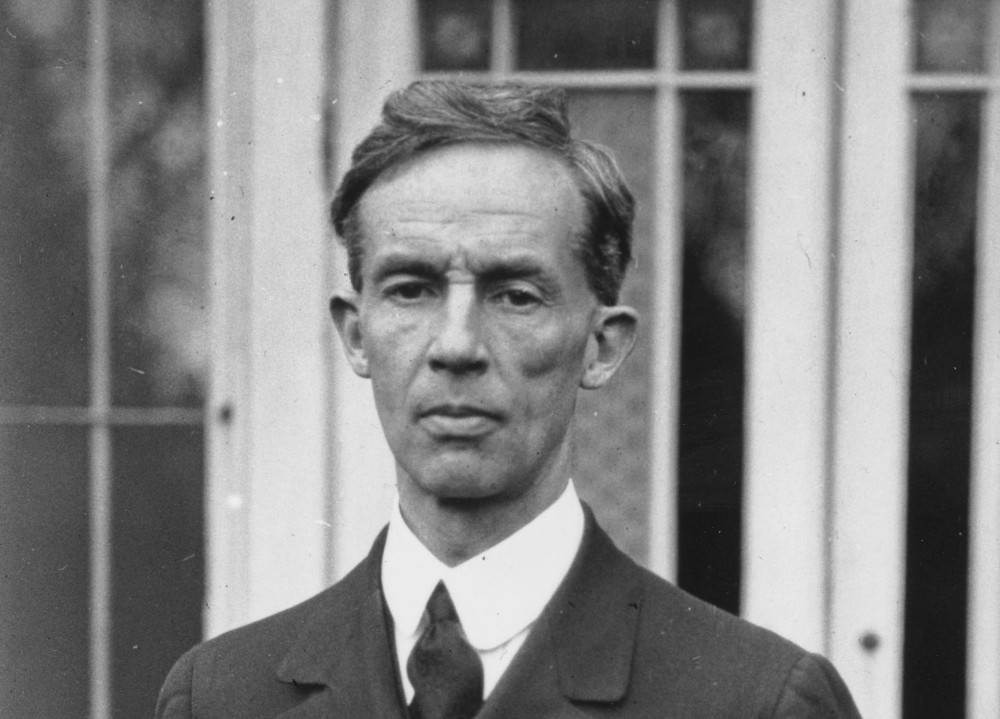

And perhaps the pick of the literary crop was 1903’s The Riddle of the Sands, by the Anglo-Irish writer, soldier, and politician Erskine Childers. The novel mixes some gentle satire about the graded snobberies of the Edwardian class system with a seafaring adventure involving a couple of topping British chaps going after German spies in the Baltic. It’s not only a riveting tale in itself, but so cogent in its account of the state of Britain’s maritime defenses that it prompted the Admiralty to hurriedly install a series of new coastal gun batteries. Childers’s book was an instant bestseller, and still ticks over today. No less a judge than Ken Follett has called it “the first modern thriller.” If you want a really gripping read, with plenty of white-knuckle action, some energetically sustained period idiom, and the mass of verifiable detail later found in the James Bond novels, The Riddle is for you.

Ironically, about the one person seemingly unmoved by the book’s success was Childers himself. Aged 33 at the time of its publication, he never wrote another novel, instead concentrating on technical military manuals and political tracts. To call Childers a man of humanizing contradictions is an understatement. On one hand, he served the Crown as a wartime intelligence and aerial reconnaissance officer, greatly distinguishing himself in the 1915 Gallipoli campaign. On the other, he was busy smuggling German-bought guns to supply the Home Rule nationalists in Ireland, running the weapons onto a moonlit beach north of Dublin on his racing yacht Asgard, accompanied by his wife Molly and a small crew. It was almost like a scene out of The Riddle, with the critical distinction that instead of sounding the alarm about German ambitions, Childers was in the curious position of serving the King while transporting arms from the Kaiser intended for a revolution behind the lines.

The 1916 Easter Rising that saw the deaths of 485 men, women and children in a week of rioting around Dublin seems to have finally clarified matters in Childers’s mind. “I am daily witness to the prostitution of the British Army I served to fulfill the many aims I loathed and combated,” he wrote. “I am Anglo-Irish by birth. Now I am identifying myself wholly with Ireland.”

Having cemented his establishment credentials by winning the Distinguished Service Cross for his work at Gallipoli, Childers settled down to live as a sort of proto-hippy on a farm in County Wicklow, extolling the virtues of vegetarianism, enjoying an occasional sniff of cocaine and a degree of freedom from the traditional monogamous ideal, and sending his three young sons to a progressive school where they would be taught nothing about religion until old enough to decide for themselves.

The war over, Childers was a victim of the Spanish Flu pandemic and barely survived. At least one of his biographers has speculated that he suffered a psychological breakdown as a result, with “an addiction to danger that amounted almost to a death-wish.” In 1920, Childers published “Military Rule in Ireland,” a stinging attack on British policy, and followed it with a series of articles in the weekly Irish Bulletin tearing the Liberal prime minister David Lloyd George to shreds. Childers was a member of the delegation that negotiated a treaty with the Brits in December 1921, providing for effective Irish home rule a year later. Following that, the Dublin government would act as a self-sufficient dominion of the British Empire, much like Canada and Australia. Lloyd George wrote in his diary of a “sullen” Childers, seething with “compressed wrath” that his attempts to bring about total Irish independence had failed. Winston Churchill went one further, calling him a “murderous renegade” and a “strange being, actuated by a deadly hatred for the land of his birth.”

The Anglo-Irish Treaty spurred Childers and others of his persuasion to take direct action in the face of what they saw as a sellout to London. After a further series of articles in the provocatively titled War News, one morning in early November 1922, Childers set off by bicycle from his home in County Kerry on the 200-mile journey to confer with Eamon De Valera and his fellow rebels in Dublin. He was arrested by British troops along the way, and found to be in possession of a small .32 caliber pistol in violation of the recently passed Emergency Powers Resolution.

The subsequent judicial proceedings were swift. Childers was taken to Dublin and put on trial a week later. The proceedings ended on November 18, 1922, after the defendant had refused to recognize the legitimacy of the British Military Tribunal to try him. The possession of the pistol was enough to condemn him to death. Childers lodged an appeal against the sentence, and this was heard the next day by a civil magistrate who said he lacked jurisdiction because of the ongoing disturbances in the area. “The prisoner disputes the authority of the Tribunal and comes to this Court for protection,” the judge wrote, “but its answer must be that its jurisdiction is ousted by the state of war that he himself has helped to produce.”

Early on the morning of November 24, 1922, Childers, now a thin, frail-looking man of 52, was led into a tin-roofed shed used as a firing range on the Beggars Bush barracks in Dublin, where a row of twelve soldiers was waiting for him in front of an open coffin. Perhaps nothing in the life of this brilliant and troubled figure became him like the leaving of it. After shaking the hand of each member of the firing squad, his final words were: “Take a step or two forward, lads, it will be easier that way.”

A few hours earlier, Childers’s 16-year-old son — also named Erskine, and a future president of Ireland — had been allowed to visit his father in his cell. The condemned man made him promise two things: that he would forgive every minister in the provisional government who was responsible for his death, and that if he ever went into politics he was never to capitalize on his execution. The younger Childers kept his side of the bargain, and in later years sometimes produced a scrap of paper on which his father had written his last testament: “I die loving England, and passionately pray that she may change completely and passionately towards Ireland.”