I once knew a great conductor who claimed that he never boarded a plane to a new orchestra without a tube of lube in his pocket. Just in case he got lucky (which he often did).

Conductors are migratory birds who fly where their agents point them, hopping from one hotel bed to the next. There is no shortage of bright young things on an orchestra’s staff and besotted fans backstage who are open to a wink and the whisper of a room number. A maestro is never alone for very long.

Sex is one of the perks of conducting. Mostly, it’s consensual. My middle-aged maestro would sit up half the night reading poetry to a young woman before he made anything so crass as a lunge. Down the years, there have been few complaints about maestro sex. Seduction techniques vary. An opera conductor I know makes eye contact at the first rehearsal with younger members of the chorus, one by one, until someone stares right back.

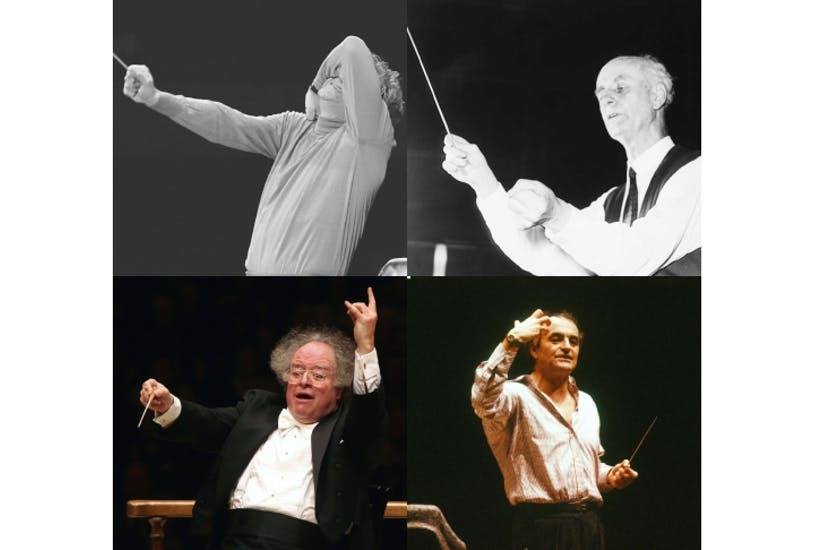

Inevitably, in so gregarious an activity as opera, everyone knows. They have always known. They knew that Wilhelm Furtwängler’s secretary would bring a woman to his dressing room before a concert. They knew that Georg Solti was a Lothario at Covent Garden (he told me so himself). They knew that certain Italian maestros were too free with their hands, that Leonard Bernstein preferred young males, that an early music master was a philanderer.

They also knew that there were certain conductors with whom you did not go alone into a room. Interns were warned about them. Not always in time.

All this has tended to be seen in the musical world as a joke. And this has, on many occasions, given cover to greater abuses, which are only now coming to light.

The most serious case I know of is the soloist in her late teens who was summoned to the conductor’s room in one of Europe’s most famous halls an hour or so before a concert to discuss a few points in the score. She emerged a while later, sobbing uncontrollably. She had been raped, and she still had to go on stage, perform a concerto, and take a bow with her rapist. I have tried to persuade her to speak out, but she — understandably — wants to get on with her life and is probably still more than a little afraid that the man who raped her can, after all these years, still damage her career. Several music insiders saw her come out of that green room. Nobody confronted the aggressor.

Because sex is taken for granted as a conductor’s prerogative. Never an act of love, it is a raw and explicit expression of power. The deal is: sleep with the maestro, or you’ll never work again.

And the threat is very real. A French soprano, Anne-Sophie Schmidt, has recently disclosed that, after she refused the persistent advances of Swiss conductor Charles Dutoit in the mid-1990s, work in her diary dried up for the next year. She is convinced that the conductor blacklisted her.

Dutoit, 81, was suspended from conducting last month after multiple allegations of sexual harassment dating from the 1980s to the past decade. The incidents, which his accusers allege took place in all sorts of places including Dutoit’s dressing room, a hotel elevator, a car, involve several cases of the conductor forcing himself on musicians. In one case, he ‘shoved’ his tongue down a singer’s throat. In another rape is alleged. He has denied the reports, consulted his lawyers and vowed to clear his name. His former orchestras have promised independent investigations. Whatever the outcome of these inquiries, no one doubts that a conductor of Dutoit’s rank — former music director in Montreal, Philadelphia and London’s Royal Philharmonic Orchestra — has executive power. To give one inoffensive example: in 1990, Dutoit installed his girlfriend Chantal Juillet — later his fourth wife — as concertmaster of the Orchestre Symphonique de Montreal. Such promotions are in the music director’s gift.

Far more pervasive is the power of silence. An American administrator contacted me recently to report that, while he was a twentysomething music staffer at the Metropolitan Opera, the Met’s long-serving music director James Levine approached him and ‘stuck his hand down my pants’. The young man indicated that he was not interested.

From that day on, the young staffer was shut out of all music activity in the building. No one, he says, wanted anything to do with him because Levine — or those around him — had put out word that he was persona non grata to the music director. Like a Premiership footballer who is benched by the manager, all he was ever told was ‘you’re not good enough’. The ostracised victim in this case had enough sense to get out and make his life far from the maddening Met. Others stay on in a state of demoralisation until they are unfit for work.

Levine was suspended from conducting at the Met last month after claims that he molested young men in Chicago, Boston and New York, which he denies. The allegations have not been tested in a court, and may never be resolved. What is undeniable, however, is that anyone at the Met who did not get on with Levine during the 41 years he was music director had absolutely no future in the place.

Abuses of power are not random or incidental. They are as routine in music as they are in Putin’s Russia, where all authority flows from a short man with a little stick. It is rare for that authority to be challenged and rarer still for the challenger to survive.

Classical music conducts its business behind a screen of secrets, lies and euphemisms. A maestro is never absent without leave, only ‘indisposed’. No maestro ever gets fired. He becomes Emeritus.

Truth gets buried beneath a dungheap of flummery. The real reason for the recent departure of at least one classical performer in this country will not be publicly explained, even though it is well known backstage. The code of silence in classical music is as tight as Sicilian omertà. Speak out, and you’re dead meat.

As the writer who exposed The Maestro Myth at book length a quarter of a century ago, I am encouraged that victims of sexual assault have now found the courage to breach the taboo of silence. But the denial is not over. Montreal, unaccountably, has yet to begin its investigation and the Met has made clear it may never publish its findings. Without a commitment to transparency, the likelihood of further abuse remains.

In 2000, when James Levine was named music director of the Verbier Festival Orchestra, whose players are as young as 16, I asked the festival’s founder, Martin Engstroem, if he knew the risk he was taking. He assured me that special precautions had been put in place. When the accusations against Levine came to light last month, Engstroem professed himself ‘disturbed and saddened by these accusations’. Levine’s successor at Verbier was none other than Dutoit. Engstroem would have been shocked again.

Now, let it be clear that many conductors lead exemplary and rather boring lives, their heads filled with musical minutiae and cast changes. Some are escorted at all times by closely observing wives. Among the more lascivious maestros, it is widely acknowledged that some are generous and tender-hearted. Solti was always sympathetic to injustice in any institution where he worked and quietly supported dozens of hard-luck cases. No one ever accused him of taking advantage of women, any more than they did Mick Jagger or Roy Jenkins. I know singers who said no to Solti and went on to work with him happily for years. Not all maestro sex is abusive.

At present, there are two frontline music directors who regard the workplace as their private casting couch without being accused of anything untoward. They may be more careful in future but the compulsion will not abate because the cause is embedded deep in the maestro psyche.

One podium giant of pre-Viagra times told me he decided to retire from conducting the day his virility wilted. Without a sex drive, he could not face an orchestra. The relation of baton and penis is more powerful than many maestros are prepared to admit. For this to change, we need to see more women on the podium. Once the gender balance shifts, sex should be less of an issue.

Norman Lebrecht is author of The Maestro Myth: Great Conductors in Pursuit of Power.