All worthwhile horror films are products of their culture. They distill its neuroses and fears, forcing protagonists to make value judgments with life-or-death stakes. And that’s why the genre continues to compel: beyond the adrenaline rush of jump scares, watching old chillers is like opening a metaphysical time capsule. They show how past generations understood their world.

The exorcism subgenre tracks that pattern — only its questions tend to be explicitly religious. William Friedkin’s 1973 classic, arriving at the height of modernist theology, directly foregrounded the question of faith within a liberal world order. Scott Derrickson’s 2005 The Exorcism of Emily Rose, released during the heyday of “New Atheist” scientism, quite literally put “God in the dock,” raising questions of the supernatural through a courtroom drama. The Rite (2011) featured a postmodern clash of worldviews. And so on.

This year’s The Pope’s Exorcist is no different. Like last year’s Prey for the Devil, it approaches the demonic through the lens of trauma, casting “evil” as the ne plus ultra of tragic experience in good contemporary form. Here, demons steal upon vulnerable subjects and lead them astray, not tempting them into sin but overpowering them. Whither the human will?

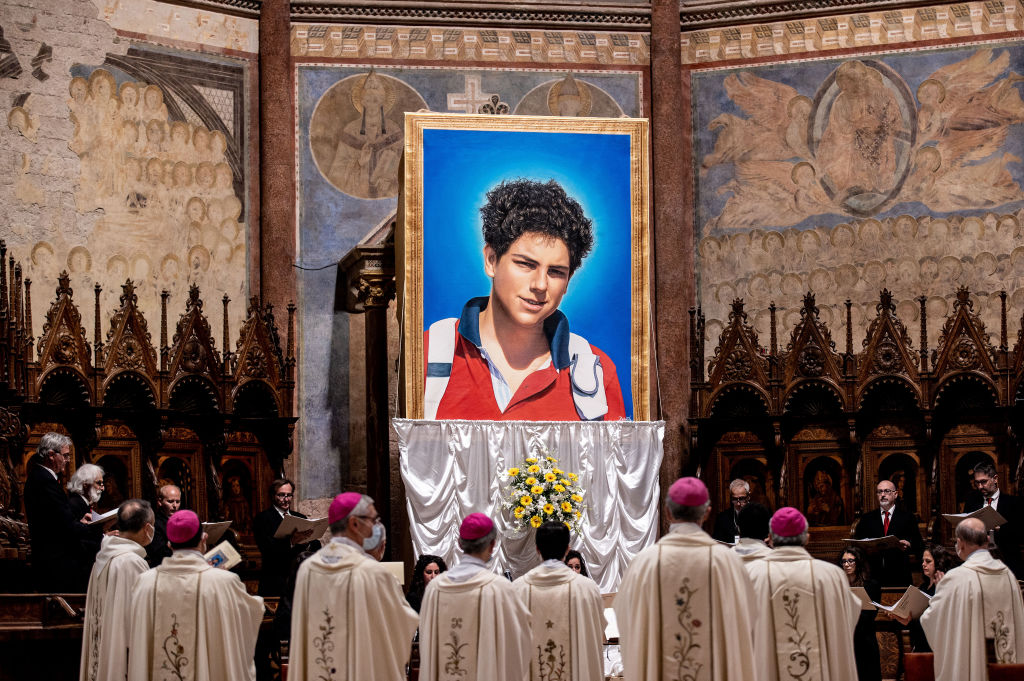

Russell Crowe stars as the eponymous (late) priest Gabriele Amorth, the Vatican’s highest-ranking exorcist. Amorth’s strong sense of the supernatural puts him at odds with Vatican bureaucrats under the reformist spell of Vatican II, but the Pope consistently backs him.

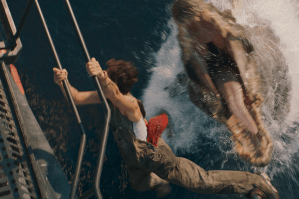

When reports of a potential possession in Spain surface, Amorth is called into action: while renovating an old abbey, a family has come under attack from a strange supernatural force. With some help from the local priest, played by Daniel Zovatto, Amorth sets out to expel the demon and save the child’s life.

For fans of the genre, these plot beats are all familiar. Indeed, almost everything here is derivative of better films, especially Friedkin’s. (Levitation? Vomit? A child spewing vulgarities? A spider walk? Yes, you’ve seen all this before.) The third act takes a bit of a Saw-meets-Constantine turn, which is visually creative and quite entertaining, but it’s hard to make up for how much the build-up sags.

To be sure, even old tropes can be used well, but director Julius Avery is no James Wan. Despite its R rating and Crowe’s committed lead performance, The Pope’s Exorcist simply isn’t as scary or menacing as it needs to be. For all its creepy imagery and expensive-looking sets, it never really indulges its most gothic impulses. Instead, what ends up onscreen feels more like a decent episode of Supernatural than a multimillion-dollar drama.

And from a thematic perspective, the film’s interpretation of demonic possession raises a great many questions. Are the church’s failings — such as sexual abuse — a result of human sin? Or are they products of demonic infiltration? And if demons can wrest control of people without their consent, how responsible is anyone for their actions? Potentially compelling questions of guilt and trauma and moral accountability swirl under the surface, but no attempt is made to answer them. More’s the pity.

In the end, the best approach to this kind of story may be the simple recognition that less is more. The demonic need not be schematized or allegorized or explained away, but left to sit there in its alien horror: just consider the dreadful figure of Valak, who towered over The Conjuring 2 and The Nun. The Christian tradition upon which all these films draw has understood demonic evil as an ancient predatory power, hateful and utterly bent on humans’ annihilation. And that concept, when laid out in its starkness, is frightening enough — no cracking bones or swear words required.

Father Amorth’s career was profoundly fascinating, and his career raises a host of important questions (as the 2017 documentary The Devil and Father Amorth described). Alas, he deserved a better cinematic outing than this.