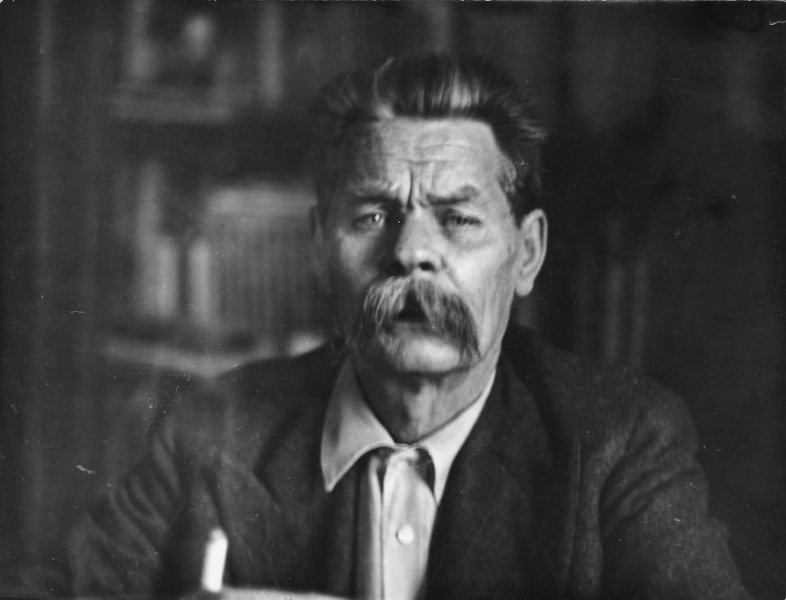

The writer Maxim Gorky edited the Menshevik newspaper New Life during its short run from May 1, 1917 to July 16, 1918, before Vladimir Lenin gave the personal order to shut it down. Gorky was a one-time friend of Lenin’s and a committed socialist (when Lenin gave the order to shut down New Life, he is reported to have said, “Gorky is one of us”), but he was also a frequent critic of the Bolshevists.

In his column for the paper, which ran under the heading “Untimely” — because it focused on culture and morality rather than on practical matters of the revolution — he complained frequently about the politicking of party leaders and the stupidity of the masses. “Polemics is the dearest occupation of those who like scholastic exercises in wordmongering,” he writes in one column. In another, Gorky lambasts the Russian people for being lazy “seed-chewing” children. They have no “love for their native land” and no “sense of responsibility for the fate of Russia.” The only thing they care for are their “deadly sins.” Lenin himself was an occasional target. “Lenin is not an omnipotent magician,” Gorky writes in one column, “but a cold-blooded trickster who spares neither the honor nor the life of the proletariat.”

In these columns, which were collected as a book called Untimely Thoughts and published in 1918 (and just as quickly suppressed), Gorky argued that a cultural revolution needed to take place in Russia before a material one. The masses lived for the immediate moment and were incapable of thinking, acting freely and living virtuously. As long as they had a few pleasures, he argued, they were happy to live under the control of the monarchy or state. Gorky saw, too, that party leaders were just as hungry for power as the aristocracy and that what would follow a revolution would not be a new world but another version of the old one.

Like his fellow Marxists, Gorky had a dim view of the past. “Our most merciless enemy,” he writes, “is our past.” “Is it possible,” he continues, “that we are unable to find within ourselves the strength to get rid of its infection, to throw off its filth, to forget its bloody outrages? A greater maturity, a greater thoughtfulness and wariness with respect to ourselves — this is what we need.” And it was “culture” — specifically literature — that could provide this maturity. Russia, Gorky writes, “must be tempered and cleansed of its inbred slavery by the slow flame of culture.”

This is why freedom of speech was so important to him — without it how could writers possibly do what was needed to create new people and a new country? He derided the groupthink of parties that harass those who do not “behave with sufficient ‘loyalty’ toward the sacred interests of the ‘right-thinking people.’”

But in the end, Gorky trusted people too much — despite his criticism of the masses, he thought of people as morally neutral, easily shaped by culture — and he trusted culture too much. He believed that if the intelligentsia, “from the first days of freedom, had tried to introduce other guiding principles into the chaos of aroused instincts, if it had attempted to arouse feelings of a different order—none of us would have experienced the multitude of those abominations which we are now experiencing.”

But the idea that literature in particular, without the family or the church, could transform an entire country in a few years is absurd. Such a change requires generations and the commitment of all aspects of society — and even then, the outcome is far from sure. For all of his good sense about the importance of free speech, the depravity of the political elite who have no sense of duty except to themselves, and the dangers of a decadent culture, he lacked the maturity to see that the game he was playing (or wanted to play) was the long one.

He left Russia (for the second time) in 1921 but returned a few years before his death in the early 1930s. He became a propagandist for the Soviet regime, even if privately he found himself in opposition to Soviet positions, particularly when it came to censoring writers. He died in 1936 and was touted as the father of socialist realism, even though he spent his final years under house arrest. The man who railed against the slave mentality of the Russian people ended his life a slave.