The Thing is not a monster movie. Sure, John Carpenter was remaking the 1951 The Thing from Another World, itself an adaptation of the 1938 pulp-sci-fi novella Who Goes There? — but it’s not a shlocky B-movie horror. It’s too vicious, cynical and psychological for that. Rather, it’s the ultimate paranoia thriller.

For the unfamiliar, the 1982 flick is about a group of researchers, stuck in an Antarctic base, who discover a strange shape-shifting alien, which consumes its victims and then mirrors their look, smell, speech and manner. They’re all marooned together, being hunted down by an unearthly terror, and any of them — friend, stranger, dog — could be it, waiting to strike. It doesn’t end with an epic explosion, or a corny teaser to the sequel, or wholesome tears as our mysterious alien visitor goes home on an ethereal vessel. It ends with a cold, hard scene as two men stare at each other, slowly freezing, neither knowing if the other is the monster, with fire and endless ice behind them, and death awaiting. The same year that E.T. made bicycles fly and families smile, John Carpenter’s Thing said we’re all doomed.

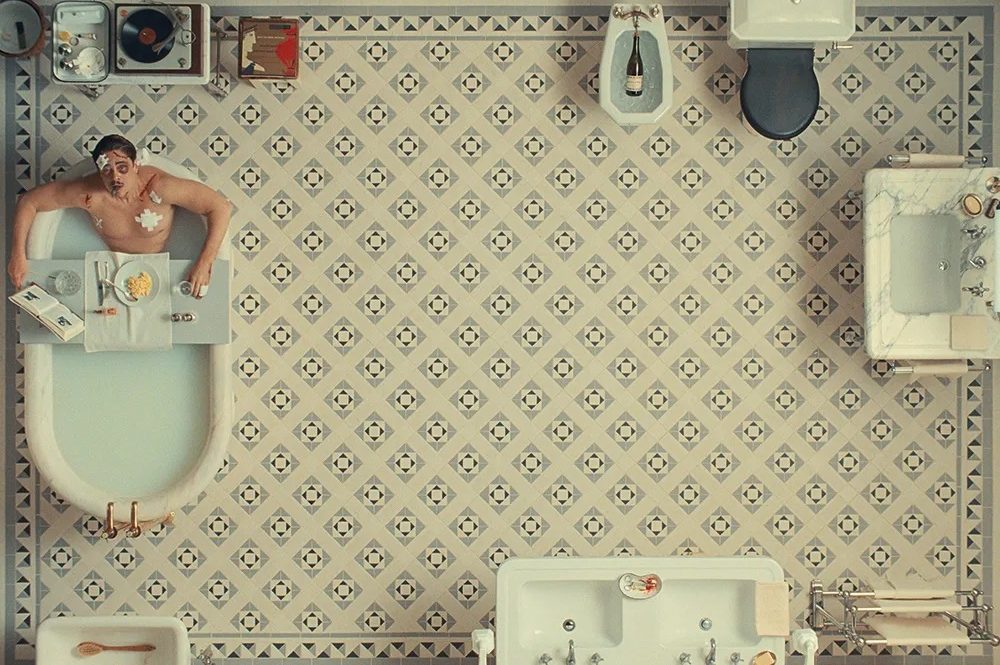

It’s a masterfully written, acted, edited and directed film, but the glue that holds it together is well, the glue, and rubber, and mayonnaise, and stop-motion tentacles and alien puppets that bring its Lovecraftian monstrosity to life: from a decapitated head with spider legs, to a husky whose face splits open and becomes a bloody pile of sinewy molasses, to the man whose chest rips open to expose a massive mouth, ripping the arms off a doctor before spitting green tendrils and erupting an enormous spindly tendril of brown flesh, atop which sits a melted image of his own head.

More than a third of the film’s budget was spent on the effects work. The twenty-one-year-old effects lead, Rob Bottin, worked seven days and nights a week for more than a year to make it happen. He was hospitalized with exhaustion and pneumonia on completion of filming, but he created some of the greatest body-horror effects ever put on film.

“Body horror” is a uniquely physical, rich, allegorical form of horror filmmaking; it had its dominance in the 1980s, notably through the filmography of David Cronenberg, but continues to inspire effects artists, writers and directors to this day. Cronenberg’s latest film, 2022’s Crimes of the Future, is set in a dystopic near future, where artists can grow new organs and tumors inside their bodies, only to cut them out as a performance for a live audience. The most important line in the film defines this genre — “Body is reality” — it says that by warping and distorting the body, you reflect the world around you.

Oscar Wilde has a character observe that “every portrait that is painted with feeling is a portrait of the artist, not of the sitter,” and though films like The Fabelmans are the most literal reflection of this point, body horror is uniquely adept at this self-reflection. The “thing” is not some green-headed extraterrestrial; it’s the monstrous embodiment of social collapse, of the rot of trust and the crumbling of the mind.

Cronenberg’s 1986 The Fly is a remake of Kurt Neumann’s 1958 B-movie horror of the same name — which critic Ivan Butler aptly summarized as “the most ludicrous, and certainly one of the most revolting science-horror films ever perpetrated.” The core of the two films is the same but Cronenberg has stripped his film of anything ludicrous. It’s no longer about a fly-man monster; it’s about how a charming, funny, handsome, decent man (played by Jeff Goldblum) is corrupted by obsession with discovery. The central horrifying metamorphosis — as he gradually regresses into an enormous, wet, hairy, fly- man hybrid — is just the physical embodiment of this corruption.

The central metaphors of body-horror films are often blunt, and a tad elementary, but when it’s rendered in ripped flesh, the viewer doesn’t notice. Complaining about the harm of television entertainment sounds very boomer, but Cronenberg’s 1983 Videodrome is gripping and horrifying in its exploration of snuff TV. Environmentalism and concerns about climate change make for terrible films, but Crimes of the Future made it work; one of the greatest films never made is Karyn Kusama’s proposed transition body-horror film, about a man whose body slowly transforms, against his will, to become that of a woman.

Find a theme or a genre, and there’s a probably a body-horror version of it. The best coming-of-age film in recent years was Julia Ducournau’s Raw, a sensitive depiction of feminine pubescent self-discovery, where a vegetarian girl discovers she’s actually a cannibalistic creature. Tetsuo: The Iron Man viciously captures our dependency on technology and machinery; American Werewolf in London touches on cultural clash and isolation in a foreign country; and Brandon Cronenberg’s Antiviral examines the obsession with fame and parasocial relationships — fittingly, perhaps, for the premiere work from a son-of. He followed it up with Possessor, which is basically The Thing meets James Bond, and grapples with questions of comprehensive dishonesty, self-discovery, and personal autonomy.

In many horror films, blood and gore are just the pay-off, the red, splashy climax the director has been edging us towards. After much teasing, gradually revealing long blades in lurking shadows, with cameras that linger and a rising score, we finally get an explosive payoff, as Michael Myers pins Bob to a wall with a kitchen knife, or Frank Zito explodes someone’s head with a shotgun in Maniac, or Freddy Krueger pulls Jennifer into the TV set, before tossing her body out. Welcome to hell, bitch. And it’s great! Popcorn horror is a rollercoaster of tension and payoff, the violent and erotic, to thrill and amuse, and make teen couples pull each other close in the audience, and laugh together, relieving their tension.

Body-horror works somewhat differently. Gushers of blood and piles of cracked bones work by evoking pain; their intensity can be judged by how much you wince watching them. By contrast, body-horror effects aren’t a reward for tension — they tell a story through distortion, warping the human form beyond what’s natural — torn, stretched, warped, melted, stretched, inflated, and combined away from normality.

Rewatching The Thing, more than forty years later, these plasticine, stop-motion effects shouldn’t work — they’re cartoonish, and nobody would be confused they are anything but effects — but they make me just as queasy as audience members doubtless felt sitting in cinemas in the 1980s. In part, that’s because of Bottin’s revolutionary work, which combined every trick in the book, and invented many more. Each shot is a series of clever magic tricks, built to be seen from one angle, in one particular way of shooting, before being torn down and built up with another. It’s expensive, laborious work.

But they also stand up because body-horror effects don’t need to look utterly lifelike to be effective. We’re uniquely sensitive to the human form, and things that are close-but-not-quite-right are viscerally unsettling. And, despite how unbelievable these scenes are — men turning into flies or being consumed by their TVs or warped with green tendrils — you believe it because they’re there.

They’re real, in camera, being watched. Speaking to WIRED, Oppenheimer director Christopher Nolan remarked, “I find CGI, however versatile it is, it always tends to feel a little safe to me. I think if you want something to have a bit of bite, you want the imagery to have a bit of threat, even if it’s a miniature, even if it’s something very fake, but something real on camera gets you a better result.”

In 2011, Universal Pictures decided to make a new version of The Thing, intending to create a canonical prequel to Carpenter’s film that was, in all meaningful senses, a remake. It made sense; those Cold War themes of paranoia and existential dread rang just as true in the post-2008 financial crisis, internet-beset age of 2011, and Carpenter’s Thing was itself a remake, so what’s the harm?

If you limited yourself to watching the behind-the-scenes footage, you’d be mistaken into thinking it was a massive success.

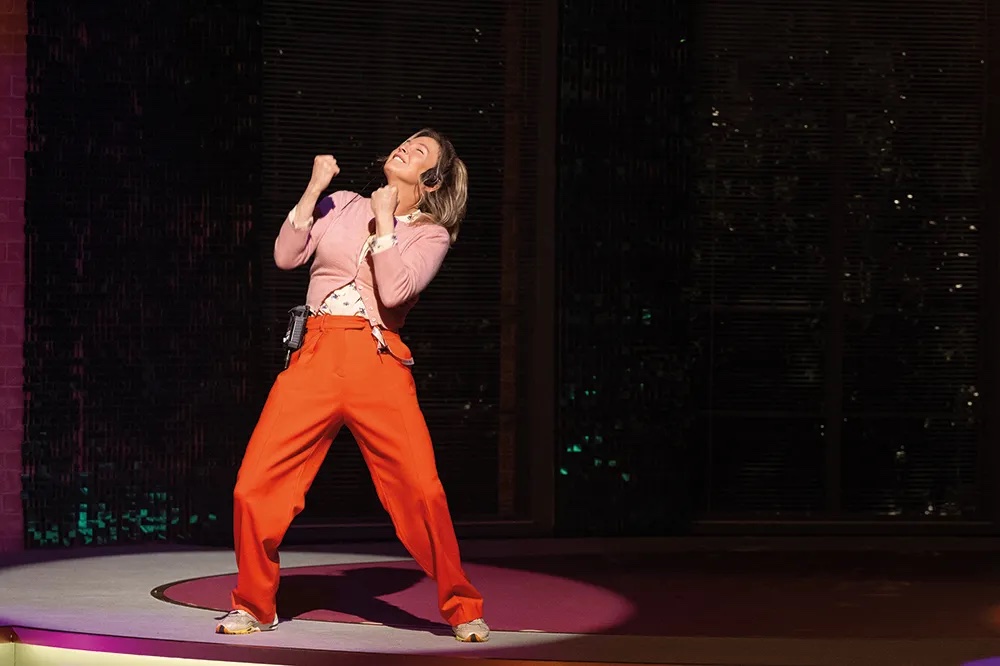

Screenwriter Eric Heisserer told the horrorcentric website Bloody Disgusting that he had a “firm, fervid belief that no CGI should ever be in this movie,” and director Mattjis van Heijningen Jr. shared this view. The script seemed solid, and the cast was too, starring the great Mary Elizabeth Winstead and Joel Edgerton. For effects, they brought in Alec Gillis and Tom Woodruff of Amalgamated Dynamics, and they shot the entire film using incredible practical effects, with mortifying animatronic bodies, which twitch and stretch on remote control. It doesn’t compete with Bottin’s work, but nothing could, and it was clear that was the bar they set themselves — their effects, like the split-head monster, are unquestionably horrifying.

But, if you watch the film, none of it’s there.

Universal wanted more reshoots, a new ending for the film, and some different stylistic elements, and the only way to quickly achieve this was to digitally remove and replace all the practical effects with new CGI versions. It doesn’t matter that these are glossy, cheap effects that have aged far worse in twelve years than the original effects have in more than forty. Universal wanted it fixed, and it was fixed. In a comment under a behind-the-scenes video on their effects, Amalgamated summarized the problems briefly: “Now that films have shorter prep scheds, it might not be until test screenings when story problems reveal themselves. By then there’s no time to rebuild/reshoot the PFX [practical effects]. [CGI] offers a more flexible way to patch holes and make “corrections” that could have been pre-empted by proper planning. [CGI] artists aren’t happy about not being given enough time to do their jobs properly. It’s a lose-lose for everyone, especially the audience.”

The rise of expensive reshoots, and too little time afforded for CGI artists, is epidemic in the film industry — it’s why Thor: Ragnarok, with a budget of $180 million, has CGI shots straight from a student film — but horror films are uniquely affected by this.

Horror is more effects-heavy than most genres, can be made cheaply, and horror films are among the few films to consistently turn major profits. Blumhouse is the most profitable production company on this model, and they’ve become so by producing dozens of horror movies a year, most of which have a budget between $2 million and $10 million. If just a third of those become multi-hundred-million-dollar hits, then they’re happily in the black.

But that requires that horror films are made quickly and cheaply, and can be reshot easily, to account for customer tastes. The best practical effects are visual illusions that work from one angle, in one shot, combined in a carefully planned sequence with other shots. But producers don’t want that, not least because they can’t afford it.

Howard Berger — the two-time Oscar nominated makeup and visual effects artist — relayed the same feeling to me, but said just how fixable this is.

“I truly believe that if production would allow more time for the director to shoot more quality as opposed to quantity, there would be more in-camera magic happening,” he said. “I recently was on a show where we disregarded this directive, rigged the actor with a complicated gore makeup effect, went to set, shot five takes dry of blood.

The director was not happy with how it was going. I went over to him and said, ‘You know, he’s rigged to bleed. Let’s do the last take with blood.’ The director agreed, we shot it, and it was fantastic! That is the shot they used, no VFX, just a little extra time on set and boom, the shot was achieved successfully in camera.”

There are new, young directors who are keeping body-horror alive and twitching, and showing how wonderful practical effects are. Brandon Cronenberg — son of David — continues to make potent, gripping entries with Neon studios, and A24 has been celebrated for letting their directors show off their styles and actually create great effects. The effects legend Phil Tippett took a pause from his work for big studios to produce Mad God, which became Shudder’s biggest film last year; it’s an insane stop-motion horror spectacular. But this is only a small part of the industry, and the future is bleak.

“Truthfully it is not VFX that is the worry of the future of makeup effects,” Berger told me,“VFX is a great tool for us as we are a great tool for them.” The problem is that the studio system doesn’t allow new young artists to flourish and practice the craft of effects-creation, and obsessives like Bottin and Berger — who grew up as “monster kids,” as Berger puts it to me — don’t have the opportunities they had in the past.

Maybe we’ll see a new generation of young horror-film makers carrying the baton of great effects, and making contortions of flesh and bone that speak to the human condition, and continue horror’s richest form. But I don’t know.

At least we can still watch The Thing and be shaken to the core.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 2023 World edition.