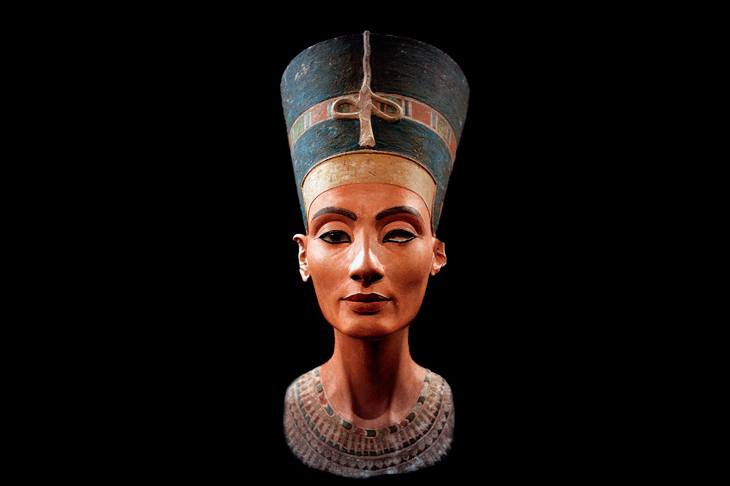

Often dubbed the Mona Lisa of the ancient world, the bust of the Egyptian queen Nefertiti is as immediately recognisable as the pyramids and the Rosetta Stone. Yet almost everything about this sculpture is mysterious at best, or bitterly controversial at worst, from the context of its creation to questions surrounding its acquisition by the Berlin Museum. The cultural and political capital of ancient culture is sharply in our awareness — think of the Elgin marbles or Palmyra — so writing a biography of Nefertiti’s bust requires the author to navigate hotly competing opinions.

Nefertiti was queen and consort to Akhenaten, a pharaoh who held power between about 1352 and 1336 BC; Egypt- ologists call this the ‘Amarna period’ after the new city he founded at Tell el-Amarna. By his fifth year, Akhenaten had promulgated a new religion focused around light. His god, called Aten, was depicted as a sun disc offering life to the king, Nefertiti, their daughters, and through them, to the world. The multitude of traditional Egyptian deities in their animal forms disappeared from official worship, and some were violently suppressed. This affected almost all areas of high culture — art, language and the performance of rulership, including queenship.

It was an extreme transformation, and the period incites extreme views in scholarship. Akhenaten has been understood as everything from a scheming megalomaniac to a divinely inspired prophet — even an alien. He and Nefertiti loom so large in our imaginations that we often lose sight of everything else, despite the results of excavations at Tell el-Amarna which reveal much about ordinary life and death in the city. ‘The myths that today envelop the Amarna royal family are,’ Joyce Tyldesley observes, ‘entirely modern ones.’

Nefertiti’s enigmatic bust sits front and centre in this heady mix. Tyldesley negotiates these myths, and the complex, fragmentary evidence that they are drawn from, in a forthright style. She will ruffle feathers in doing so, declaring, for example, ‘Akhenaten was not a monotheist’, and disputing the notion that Nefertiti took the throne after his death. I completely agree, but many won’t; and many questions remain.

The art of the period communicates its changes most obviously. Bodies became languid, with elongated heads and faces. Royal iconography became suddenly intimate: Akhenaten and Nefertiti are shown dandling their daughters, chucking them under their chins. Akhenaten is even shown munching a kebab (I dare you to find a picture of Elizabeth II actually eating). But ‘we are seeing style rather than realism’; an audience was likely meant to be shocked, or at least jolted. In this context, Nefertiti’s bust — with its refined, symmetrical proportions — is hardly extreme: rather the opposite. Tyldesley offers a nuanced discussion of the making and meaning of images in ancient Egypt, including an assessment of why we find the bust beautiful in the first place.

The story of the bust begins in a room of an ancient sculptor’s villa and workshop in Tell el-Amarna. But, as Tyldesley points out, an ivory horse blinker found in the villa is the only evidence associating the workshop with a sculptor named Thutmose. We don’t know for sure that Thutmose sculpted the bust (although Tyldesley goes on to assume that he did), nor do we know why it was made, what its purpose was, or why she has just one eye. We can’t even be certain that the bust actually depicts Nefertiti: it’s so identified purely because of her flat-topped crown. Tyldesley doesn’t offer solutions, but she lays out the arguments for us to make up our own minds, or at least to make us think twice.

Nefertiti’s afterlife in the 20th and 21st centuries is a complicated story of Egyptological competition, competing nationalisms, and the power of celebrity. The bust was found by a German Egyptologist, Ludwig Borchardt, in 1912. At this time objects of particular importance found in excavations were meant to stay in Egypt. Borchardt clearly recognised Nefertiti’s significance, but it is unclear whether he deliberately concealed this from the French official responsible for assessing the objects, or whether this official simply did not rate the bust. Should Nefertiti be returned to Egypt? ‘Nefertiti’s bust was not … obviously stolen,’ Tyldesley writes, but admits: ‘Its acquisition was opportunistic to say the least.’ The moral and cultural arguments are complex, but Tyldesley gives so much of a hearing to the Eurocentric idea that returning the bust to Egypt would place it ‘in a sterile cultural vacuum which would exclude her from the modern world’, it made me want to pop her in a suitcase and take her back to Egypt myself.

The modern reception of the bust is, for Tyldesley and many of us, bounded by museums — the ‘modern equivalent of the ancient palaces and temples’ filled with visitors who are ‘a self-selecting elite who come to admire if not to worship’. Tyldesley is interested in replication: from accurate reproductions to the sunglasses-wearing Nefertitis created by Isa Genzken. But like any icon, Nefertiti has other lives beyond the museum. I think of the hip-hop artist Lauryn Hill embodying black royalty by rapping that she is ‘more powerful than two Cleopatras/bomb graffiti on the tomb of Nefertiti’. Or the graffito of the Nefertiti bust wearing a teargas mask stencilled on Cairo walls by the artist El Zeft to acknowledge the women of the 2011 revolution. These hint at what is beyond the dominant Western narratives articulated in this book. There are always other stories to be told, or sung, or graffitied. Maybe after Tyldesley’s elegant introduction, we will begin to hear and see them.