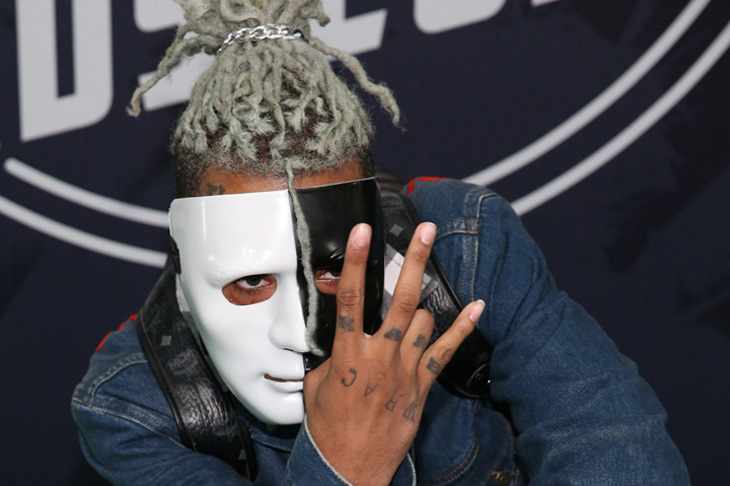

In June, a 20-year-old man called Jahseh Onfroy was murdered after leaving a motorcycle dealership in Deerfield Beach, Florida. Onfroy was a rapper, who recorded under the name XXXTentacion, and he had become extraordinarily successful — his two albums had reached No. 2 and No. 1 in the US, despite moderate sales, because of the amount of online plays they had received. The day after he died, my social-media timelines were full of music writers discussing his death, and the tenor — from those with kids, at least — was clear.

Post after post noted that XXXTentacion was a nasty piece of work, and few should mourn him, yet the writer’s 13- or 14- or 15-year-old was devastated by his death.

XXXTentacion was, it is true, a nasty piece of work. He served time in prison for armed home invasion, robbery and aggravated battery with a firearm; he was also arrested after being credibly accused by his girlfriend of beating her while pregnant.

It was after his arrest that XXXTentacion suddenly, startlingly, became popular, especially with teenagers who discovered his music through the online free music service SoundCloud. The single that broke through during his incarceration, ‘Look At Me!’, is a remarkable and alarming record — dissonant, disturbed and alien-sounding, with lyrics calculated to offend: ‘I took a white bitch to Starbucks/ That little bitch got her throat fucked.’ It’s hard as an adult not to tut. But XXXTentacion always sounded different: ‘I Don’t Even Speak Spanish Lol’, from his final album, sounds like an utterly conventional Radio 1-friendly summer jam; ‘Pain = Bestfriend’ veered from indie folk to nu-metal. XXXTentacion’s was a perfect representation of teenage listening habits: indiscriminately varied.

Though XXXTentacion is an outlier — not least because he became successful in mainstream terms — he exemplifies something that seemed to have disappeared from pop music: the generation gap. He represented something that happened away from the pop consciousness of adults, even those who like to think of themselves as in touch with pop culture.

There was a point at which it appeared that music’s generation gap had gone for good. In the 1990s, British broadcasters and publishers realised there was a generation that had grown into middle age with pop, and were showing no signs of deserting it. TV programmes were created to cater to this audience: Later… with Jools Holland was launched in 1992, putting young artists alongside what became known as ‘heritage rock’ acts. Mojo and Uncut magazines (1993 and 1997 respectively) mined the past, alongside a selection of younger music. Radio 2 became cooler; the BBC launched6 Music in 2002 for the oldies who wanted to feel youthful. Concurrently, the old bastions of teen-specific music disappeared: Smash Hits finally limped to its death in 2006, and the Saturday morning TV pop programmes were replaced by cookery shows.

Parents and kids not only knew the same things; they often liked the same things. All music knowledge came through a handful of gatekeepers — radio, TV, record companies, print media — and there was no isolated space for anything uniquely teenage to thrive. Periodically, there were hints of moral panic — in 2008, the Daily Mail warned, laughably, that ‘no child is safe from the sinister cult of emo … [a] teenage craze that romanticises death’ — but teenagers could withhold no pop secrets from their parents. Even if you didn’t listen to what they liked or like what they listened to, you knew it existed.

What changed everything was the advent of music distribution via the web — especially YouTube, SoundCloud and Spotify. Here was a place where kids could discover music without adult approval or knowledge. It’s not that the music is obnoxious, necessarily — though some of it is — more that it happens without permission, so to speak. When I was asking my 17-year-old daughter about a teenage singer called Jimothy Lacoste (137,500 monthly listeners on Spotify, a video with 287,000 plays on YouTube), and asking why I hadn’t heard anything about him, she explained that I wasn’t meant to have heard of him because he sang specifically for and to teenagers. When I look through my 14-year-old son’s Spotify playlists, I find artists who he and his friends adore, but who appear to have no mainstream media presence at all — mysticphonk, Brennan Savage, yunggoth, brobak (a laissez-faire approach to capitalisation appears to unite many of my son’s favoured artists). These people exist only to those whose cultural lives are lived entirely online: to teenagers.

All of this is, obviously, a Good Thing. Pop was invented for teenagers, and it’s wholly appropriate that it should have outposts that are completely remote to me. The teenagers sniggering at XXXTentacion’s misogynistic lyrics are no different from me, 35 years ago, thrilling to the satanic themes of Mercyful Fate albums. And nothing, surely, could be as dispiriting to a teenager playing a new song as their mum and dad saying — as I have, on occasion — ‘Oh, yeah, I knew them. I preferred their early stuff.’ Let the teens have their space, and let me finally get the chance to emulate my elders: ‘There’s no melody. I can’t tell if that’s a boy or a girl.’ Thank goodness for the return of the generation gap.