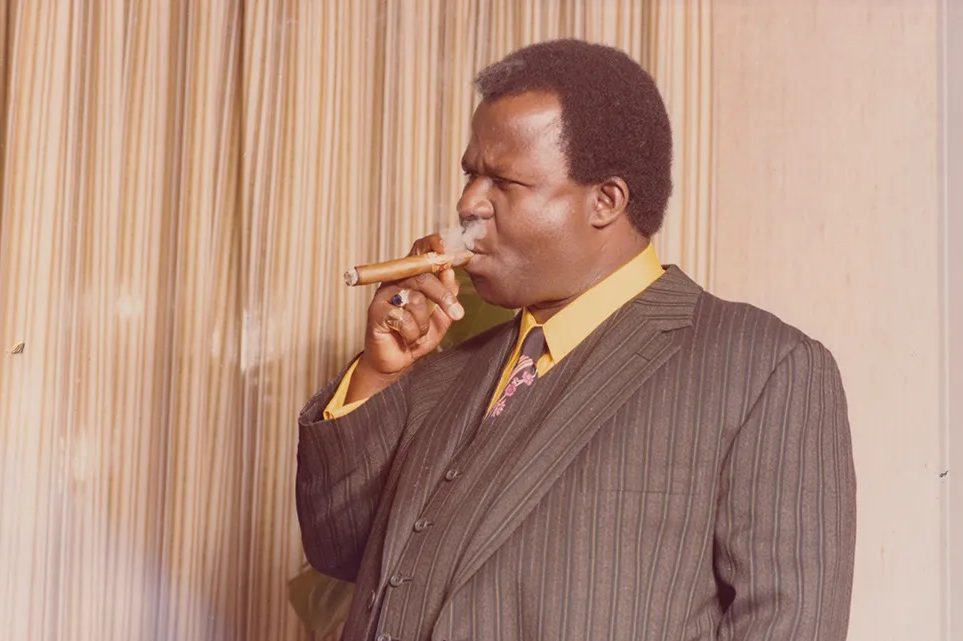

In the early months of 1981, investors in a Swiss fund stuffed with cash, diamonds and gold began arriving at a five-star London hotel to await an audience with the fiscal wizard making them fabulously rich. Dr. John Ackah Blay-Miezah would turn up in his gray chauffeur-driven Rolls-Royce, clad in an immaculately tailored suit and clasping a big cigar in bejeweled hands. Then he would regale them with tales from his student days at the University of Pennsylvania, even singing the famous Penn fight song, and talk of developing Ghana using wealth plundered by his close friend Kwame Nkrumah, the country’s first post-independence president.

‘No one could create such a story,’ said one investor. ‘It simply has to be truej’

Among the crowd was Barry Ginsberg, an American lawyer who originally put $5,000 in the fund on a promise of returns ten times higher. These failed to materialize, but he kept on investing and persuaded friends, his father and other family members to follow suit. He even helped pay for the fund’s offices. When the attorney worried about such lavish spending, he consoled himself with thoughts of the huge wealth heading his way. After ten days waiting for his meeting, Ginsberg was escorted into a dark room filled with the smell of incense and sounds of classical music. Blay-Miezah put his arm around him when asked about the timing of payday: “Soon, brother Ginsberg. Very soon.”

The entire scene was a charade. There was no Oman Ghana Trust Fund and Nkrumah did not cream off vast sums before his overthrow in a coup. Indeed, the suggestion that he ferried thousands of gold bars to Switzerland and then handed control of these riches to someone who would have been a teenager at the time was simply absurd. Even Blay-Miezah’s name was faked, along with his claims to be a doctor, to have studied at UPenn or to have been with Nkrumah at the former president’s deathbed in Romania. “I lost touch with reality,” admitted Ginsberg later.

He was far from alone — as revealed in this compelling story of a charismatic conman who fooled thousands in order to fund his opulent lifestyle as he flitted around the planet using penthouse suites and private chefs. Yepoka Yeebo describes how a small-time huckster created a story to make a few bucks about repatriating Ghana’s stolen gold, only to see it grow so vast and ensnare so many people that he ended up running for his nation’s president as the anti-corruption candidate in a bid to beat his inevitable fall.

His real name was John Kolorah Blay. He grew up in poverty, a precocious child who earned the nickname “Kerosene Boy” from selling fuel to fund his studies. Such was his charm and gift of the gab that even when serving a prison sentence for fraud he managed to persuade Ghana’s military ruler, Ignatius Kutu Acheampong, to give him a diplomatic passport to liberate the nation’s supposedly stolen wealth from Swiss bank vaults. Then for almost two decades, he told the same yarn again and again, despite its obvious flaws, surviving coups, court cases, jail cells and scraps. “No one could create such a story,” said one investor. “It simply has to be true.”

He played on avarice by dangling dazzling wealth before the eyes of suckers and stooges. Ginsberg’s group put in more than $1 million and were offered first $52 million, then later $150 million. “If you don’t think it’s fair repayment, just tell me,” said Blay-Miezah smoothly after handing over a promissory note. Such investors were summoned to the Austrian Alps, the Caribbean or London to collect their cash, only for another hiccup to delay payouts, forcing the hasty flight of Blay-Miezah to fix things. When all else failed, he feigned ill-health — a trick learned early in his criminal career. When he needed popularity, he used the increasingly familiar tactic to clean up his image of buying a football team and using cash to turn them into winners.

Some victims who came in contact with Blay-Miezah lost everything, including the self-made millionaire owner of Ghana’s first local brewery. His sidekicks included the owner of a Muswell Hill video studio and the disgraced former US attorney general John Mitchell, the most senior figure jailed over Watergate, who was promised $733 million and then used to reassure investors. Shirley Temple Black, the former child filmstar serving as US ambassador to Ghana, was unusual in seeing straight through the scam artist. And Blay-Miezah’s resourceful wife Gladys was nicknamed “Columbo” for her success at ferreting out his affairs and confronting him.

This is a glorious tale of greed, exploited by an astonishingly brazen fraudster and set against the fascinating backdrop of post-colonial Ghana. He seems to have died just as his world was collapsing after exposure by US television. An official inquiry found no evidence that Nkrumah’s gold existed, but the myth lives on. And Yeebo draws uncomfortable, sometimes clunky parallels between Blay-Miezah’s theft and the actions of a grasping imperial power which hollowed out a nation and left so little behind. “After independence, almost everything had to be remade, including the story of Ghana itself,” she writes. One fraud investigator pointed out the global perception that “if you wanted to launder money, you did it through London.” Far too little has changed on this front.

Strangely, some victims sunk in so deep they ended up as evangelists for Blay-Miezah’s cause despite his constantly changing narrative and shifting excuses about his inability to access the wealth. They were like those cultists staying loyal to a leader predicting the end of the world when the apocalypse date passes without cataclysm. As Yeebo writes, they failed to question why Ghana’s government did not simply sue the banks or Blay-Miezah to reclaim their riches:

Instead they saw Blay-Miezah in his chief’s finery, spinning a tale about darkest Africa, untold wealth and a corrupt leader. And because the story — and the man — fit their preconceptions like a dovetail joint, they made up the rest of the story for themselves.

This article was originally published in The Spectator‘s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.