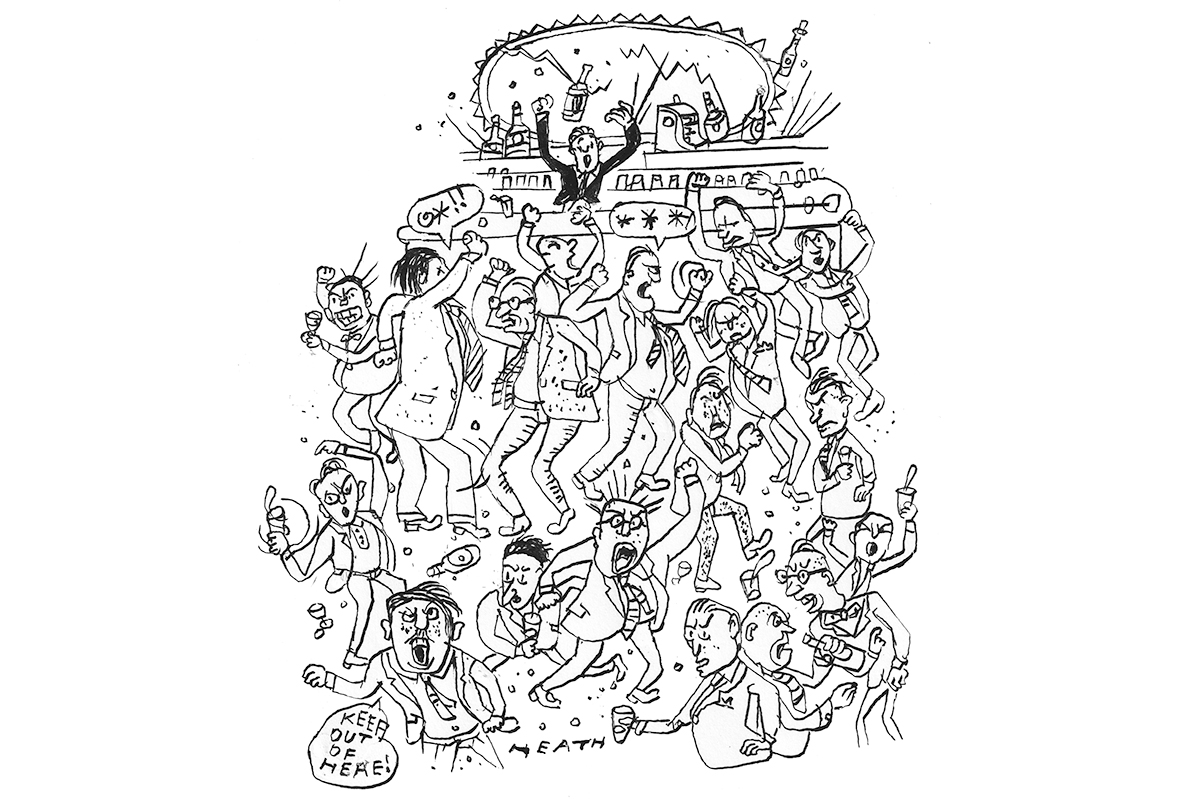

The Late Americans, Brandon Taylor’s second novel, follows the lives of a group of friends living in Iowa City over the span of a year. Early on, Seamus, a poet completing his master’s degree, imagines an “indifferent God… squinting at them as they went about their lives on the circuits like little automata in an exhibit called The Late Americans,” and this is a fine description of the novel. Each character is the focus of a chapter, and we watch as Seamus, Fyodor, Ivan, Timo, Noah, Bea, Fatima and Daw’s lives overlap, in bars, seminar rooms and dance studios, while they negotiate their place in a world determined by their race, class and wealth.

“Late” means at least two things for these Americans: they have to exist within the realities of late capitalism, but they are also too late to enjoy the security of mid-century American abundance and must make do with a precarious existence where work and relationships are hard to come by. Seamus, Noah and Fatima, all Masters of Fine Arts students, need jobs to live. They labor on building sites and in kitchens and coffee shops in temporary positions, but the careers they are working towards are no more secure (“Dance isn’t how you build a life,” Fatima’s parents tell her). Money tempts Ivan, a former dancer, now an MBA student (he aspires to be “part of that rarefied class that got to skim the money from the money”), into making adult content to earn enough to move to New York. It’s an alluring choice, and Noah tells him that his life “is going to be beautiful” and more stable than Noah’s own will be as a member of a dance company. Relationships are also a struggle. Sex is plentiful but casual; deeper partnerships are elusive. Fyodor and Timo’s founders when class and wealth get in the way.

The Late Americans is a prime example of the kind of novel that doesn’t do very novelish things (Sally Rooney writes them too). There is little in the way of plot to hold it together. Instead, the tender, elegant prose combines with sound structural unity to make it work. Its organization reflects one underlying theme: isolation. We may only spend a single chapter with each character (Seamus is unique and gets two), but this just underscores how larger forces work to keep the characters separate. In the novel, art is one way to overcome this. Goran, a pianist, can draw everyone together (“It was a moment of peace. They had all put down their weapons”). The experience of the body, with all of its pleasure and its pain, is another: “Daw wound his legs around Stafford’s waist and pulled him closer… it was no longer two bodies, but one body, sliding through itself.” Both, however, are all too brief.

In the end, Taylor’s characters can’t escape their isolation. A rare moment of pleasurable togetherness at a lake house is presented uncertainly:

What was happiness if not this moment, if not then, right then, the group of them, together for maybe the last time, coming together for this moment, for this very instant, what were they if not happy?

Connection is fleeting, and what persists is instability; even in contentment their differences threaten to take it away. They are too late, in some ways, even for their own happiness. Our best hope, according to this novel, is to cherish moments of connection even as they disappear before us.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.