Blue-collar folks are having a moment in Hollywood. Multiple directors and actors have dropped the usual disdain we see on television and the silver screen for the working class, instead unpretentiously telling the stories of down-on-their-luck rural Americans.

Nomadland, which won Best Picture at the 93rd Academy Awards in April, followed a woman who started living out of a van and working seasonal jobs after losing her job due to the closure of a local construction materials plant. Kate Winslet adopted a Yinzer accent in HBO’s Mare of Easttown, playing a small-town Pennsylvania detective that vapes and drinks her way through family trauma and a grisly murder case. Most recently, Stillwater, a film about an Oklahoma roughneck — played by Matt Damon — who attempts to overturn his daughter’s murder conviction in Marseille, France, hit the big screen in a post-pandemic return to theaters.

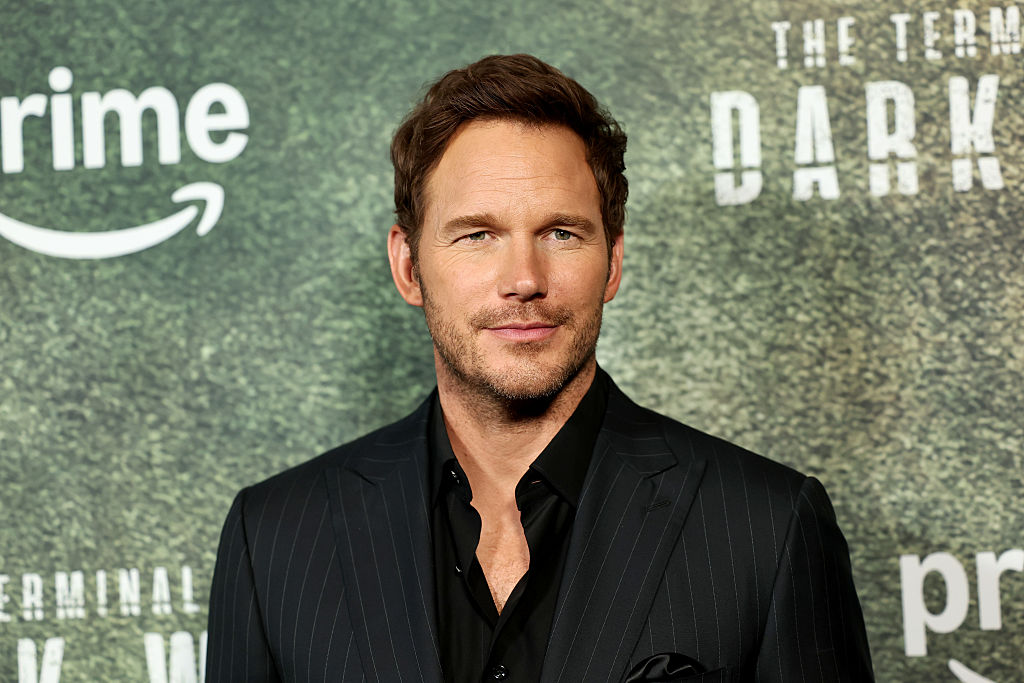

Guardians of the Galaxy leading man Chris Pratt said in 2017 that ‘the voice of the average, blue-collar American isn’t necessarily represented in Hollywood’. He later apologized, but he needn’t have — he was right. For many years, with the odd exception, Hollywood’s depictions of the non-elites were less than savory. How could it be any other way? The stars condescendingly lectured and sneered down on Trump supporters in 2016, insisting that they were the moral arbiters of the universe and far more evolved and cultured than their blue-collar counterparts. Of course that outlook would weasel its way into their entertainment. Matthew McConaughey, who describes himself as ‘aggressively centrist’ said on Russell Brand’s podcast this past December, ‘There are a lot (of people) on that illiberal left that absolutely condescend, patronize, and are arrogant towards that other 50 percent.’

That’s what makes Stillwater so damn refreshing. The movie humanizes the camo-hat and cutoff shirt-wearing segment of America while still telling an entertaining story.

Bill Baker (Damon), an oil-rig worker bouncing between jobs and trying to turn his life around, travels to France on a regular basis to visit his daughter, Allison, in prison. She is serving a nine-year sentence for murdering her Muslim lesbian lover while studying abroad. Allison maintains her innocence and is trying to get out on appeal. When her lawyer seems to think they’ve exhausted all options, Bill takes matters into his own hands.

The danger in Hollywood putting forth a blue-collar protagonist is to stray too far into fetishization. It would have been easy for Stillwater to go the route of Liam Neeson’s Taken, where the bad guys find out they’ve messed with the wrong father and are subsequently surprised by his ‘very particular set of skills’. Bill, however, is far from Superdad. Allison describes him as a ‘screw-up’ and opines that her father is too stupid to get her out of prison and will only make things worse. Even after hearing this, Bill is too hard-headed to listen to the advice of the French natives who try to assist him in his efforts. He gets beat to hell by a group of young Frenchmen after asking too many questions after dark in the wrong neighborhood and nearly sabotages the one lead he has in the murder case. The viewer later watches somewhat uneasily as Bill finds a rare spot of happiness in a surprising relationship with a French single mother, Virginie, and her precocious daughter, Maya; will he find some way to ruin that, too? The fate of this new little family starts to feel more important than that of his daughter stuck behind bars.

The film handles politics subtly, opting for broad themes over explicit commentary. In one scene, liberal actress Virginie storms out of a meeting with a potential witness when she realizes he is racist. Bill explains to her that he doesn’t have the luxury of loudly protesting against every racist he encounters, whether it is someone he works with on an oil-rig back in Oklahoma or a man who could help free his daughter. It is an astute point on the privilege inherent in wokeness. Donald Trump, the elephant in the room, is mentioned just once and handled with humor. Virginie’s friend asks Bill if he voted for Trump, and Bill replies ‘no.’ She looks relieved, until Bill blithely drops the bomb that he cannot vote because he is a convicted felon.

Damon, a long-time Hollywood leading man, registered Democrat and climate change activist, might seem an odd choice to accurately portray the complexities of Bill, a flawed small-town man trying to finally do right by his family. But Damon has somehow managed to avoid sucking in too much left-wing LA orthodoxy. He has said that he wanted to give Trump a chance in office and that he ‘root[s] very hard for the president of our country.’ He is apparently unbothered about cancel culture, recently telling the Sunday Times of London a story about how his daughter wrote him a letter in response to him using the word ‘faggot’ in a joke. He later clarified his use of the slur in response to backlash, explaining that it was common in his hometown of Boston, but did not say he was sorry.

This attitude likely endeared Damon to the roughnecks he met while doing research in Oklahoma for his character in Stillwater, who he says ‘don’t apologize for who they are or what they believe’. He talked about the understandable initial skepticism among those folks during an interview with Hot Ones.

“The roughnecks kind of met us with some understandable wariness, like, “What are you doing? What are your intentions? Are you here to poke fun at us?”’ Damon recalled. ‘Once they realized the script had all of this compassion and empathy for this character…and that we were just trying to get it right, they were awesome.’

Damon’s work to portray Bill Baker accurately paid off. Some critics have described his acting as flat, which suggests they’ve never met the kind of subtle and stoic men who do physical labor for a living. Kenny Baker, a drilling supervisor from the real Stillwater and the main inspiration for Bill Baker, was pleased with Damon’s performance: ‘The walking and the speaking, I was sitting there listening to the words, “Yep, I say that. Yep, I say that.”’

Although Stillwater has its issues — primarily that it tries to wrap up the primary plot too quickly and, as a result, the twist feels like a clumsy afterthought — I couldn’t help but love it for its bravery. It feels like a significant cultural moment that a big Hollywood film was unafraid to portray a Trump-supporting blue-collar man with the depth and empathy that he deserves.