Sitting beneath the pergola of the historic Roycroft Inn, J.R. Seeger looks the part of a successful thriller writer. He is wearing an immaculate white shirt, blue jeans and boat shoes, his blue-green eyes peering over a camouflage-style face mask.

The western New York hotel, some 20 miles from the city of Buffalo and the Peace Bridge crossing into Canada, was a centerpiece of the American Arts and Crafts movement when it opened in 1905.

It is also the setting for one of the most gripping scenes in Seeger’s debut novel, Mike 4, in which a Russian double agent tries to lure an American protégé into a life of treason. The rendezvous involves a splintered oak door, a Colt Python .357 revolver pressed to the temple and a takedown so brutal and realistic that I half expected to find bloodstains on the carpet when I checked into my room.

A prolific writer, in the space of two years Seeger has had five thrillers in the Mike 4 series published by the Michigan-based Mission Point Press.

But John Robert Seeger — he has been called J.R. since he was a toddler so his mother could differentiate him from his father, who had the same name — is no lifelong habitué of the literary scene. While East Aurora is now an upscale small town with a main street lined with restaurants and gift shops, Seeger’s upbringing here was distinctly blue-collar. Then, the Roycroft, which reopened in 1995, was in ruins. ‘It was not a town of doctors and lawyers and architects. The ’croft was a place where the toughs would beat the crap out of you.’

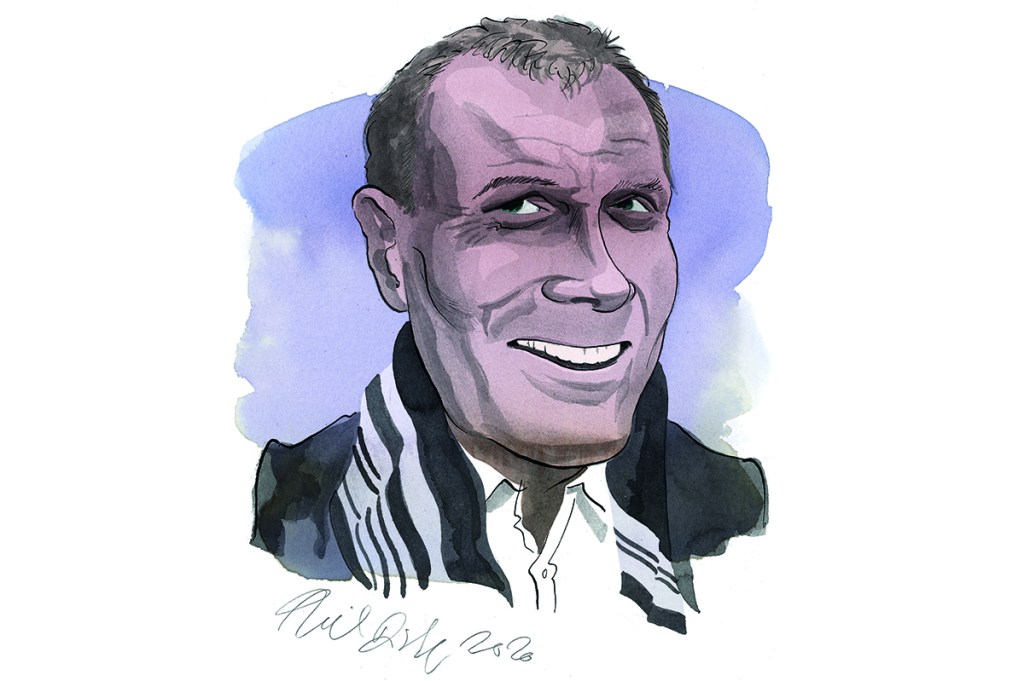

When Seeger, who is in his mid-sixties but could pass for a decade younger, stands to his full 6ft 4ins, his self-description of ‘old warrior, new writer’ begins to make sense. Even that, however, only hints at a life spent operating in the shadows.

Seeger is a former CIA officer with more than two decades of clandestine service behind him. He was a paratrooper stationed at Fort Bragg, North Carolina when a cold call from the spy agency set him on a journey that included 17 years ‘in the field’, according to his official, very limited unclassified biography, before being promoted to a series of senior executive roles. He speaks Farsi, Dari and Tajik, and was one of the CIA’s foremost experts on the Afghan psyche.

The only public depiction of Seeger is in the movie 12 Strong, about the American-led invasion of Afghanistan after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Dressed in paramilitary garb with a backwards baseball cap, an AK-47 slung over his shoulder and a pistol strapped to his thigh, he meets a US Special Forces team as they land by helicopter behind Taliban lines in the Dara-e-Suf valley.

In the movie, the CIA man is identified only as ‘Brian’, but there seems little doubt that the composite character ‘Brian’ is based on Seeger, who spent an afternoon with producer Jerry Bruckheimer during the 2017 filming of the movie in New Mexico, where, by chance, Seeger splits his time with New York. After delivering an expletive-laden intelligence brief, Brian bids farewell to the Green Berets. ‘I got a 50-kilometer hike to give a bag of money to another warlord,’ he tells them. ‘Who knows, maybe we’ll see each other on the battlefield.’ A master sergeant remarks: ‘God, that spook is cheery.’ The team’s warrant officer observes: ‘Yeah, runnin’ around here alone, settin’ this thing up. Say one thing about him, he’s got giant balls.’

Seeger approaches his writing with an enthusiasm and spirit of adventure that puts most authors to shame. He has no literary pretensions, but is willing to craft complex, multifaceted plots with an uncompromising fealty to military lingo and details of weaponry, along with extraordinary characters drawn from real life.

‘Mike 4’ is Sue O’Connell, a Special Forces operator who suffers a ‘BTK’ — below-the-knee amputation — and opts to train at the CIA’s spy school, known as the Farm, rather than retire to civilian life. She is the granddaughter of an OSS officer (the Office of Strategic Services was the forerunner of the CIA) and the daughter of a CIA ‘tandem couple’. She is, Seeger says, based on operatives he trained without knowing they were amputees.

Much of the action takes place in Afghanistan and Iraq but the continuing Cold War between Russia and the US is a recurring theme. In The Executioner’s Blade, the third Mike 4 novel, Russian mercenaries attack an American base in Afghanistan. An American colonel briefs afterwards that a defector had produced ‘a gigabyte of data on Russian organized crime efforts providing material and financial support to Iran’s Islamic revolutionary Guard Corps, Hizballah, and the Taliban’. He adds: ‘The crime syndicate had direct links to senior Russian leadership.’

Until recently, this might have been regarded as far-fetched, to the uninitiated at least. But after the recent New York Times report of Russian bounties for Taliban fighters who kill Americans, it seems prescient. For Seeger, the revelation came as little surprise. ‘Yes, it’s jaw-dropping,’ he said. ‘Yes, it is tragic. Yes, it is absolutely consistent with who the Russians are.’

Seeger’s wife, Lise Spargo, now an artist, served alongside him in the CIA, giving his fictional depictions of tandem couples an added authenticity. CIA marriages — in one book Seeger describes the Farm as ‘the most expensive dating service in the US’ — tend to be successful because deception can unite a couple rather than divide them. But some secrets remain.

Even as a couple, they operated on a ‘need to know’ basis. ‘The vast majority of what I did, the vast majority of what Lise did, we both knew. But there were compartments. In some cases, I guess I probably never did learn about them. And that’s just the way it works.’

Throughout the novels, Sue O’Connell struggles with the lies she grew up with and at one point confronts her mother, Barbara, saying that the truth is owed to members of a family, even a CIA one. ‘Yes, I owed it to you, but it is hard to stop keeping secrets once you get started,’ her mother replies. Later on, O’Connell reflects that she misses the simplicity of her old life of ‘finding, fixing, and finishing’ terrorists, compared with the intelligence world of ambiguity and opacity.

Seeger learned to deal with it. ‘Deceit isn’t necessarily the same thing as lying,’ he says. ‘There’s a phrase used over and over again in the Agency: “Everything we say is completely true. It’s just not truly complete.” You try to steer as close to the truth as possible or make sure that you guide the conversation in a direction that is not sensitive. You’re providing truth, but it’s not complete.’

As in his CIA career, a constant thread in the books is the bond between US intelligence and Special Forces. The character Jamie, a CIA paramilitary officer in his fifties, served a full military Special Forces career before being ‘trained to run agents, build secret surrogate armies, and, at night, go to diplomatic functions to spot and recruit new spies’. Seeger explains: ‘You’re not going to find me in any of these but real people are there. They will remain nameless, but they know who they are. Jamie’s a no-shit real person.’

Seeger went into battle with the British troops from Special Boat Service (SBS) in Afghanistan in 2001 and they appear in his novels as chipper, unassuming and deadly.

So far, Seeger’s books have made little impact beyond his immediate world of spies and soldiers. Whereas the likes of Valerie Plame, the CIA officer whose identity was controversially revealed around the beginning of the Iraq war, and Britain’s Stella Rimington, former director of MI5, have written blockbuster tomes with big advances, Seeger is still writing principally for personal satisfaction.

Jason Matthews, a former CIA officer of similar vintage to Seeger, wrote the book Red Sparrow, which became the movie of the same name. But that was more a work of the imagination than Seeger’s books, which keep closer to the truth and were published only after he made changes requested by the CIA’s Publications Review Board.

Seeger found major publishers disdainful of his early approaches, and dishonest, even to someone whose career had involved lying and deception. ‘I’m a retired intelligence officer,’ he explained. ‘When I submit something, I put a track in it to see if anybody’s read it. The most mean-spirited review I got was from a person who had never opened it.’

Undeterred, Seeger has a sixth Mike 4 book in the works and has begun a new Steampunk series, a subgenre of science fantasy set in the steam age. ‘It’s Rudyard Kipling meets Stan Lee’s Doctor Strange. So there’s espionage, but there’s mysticism. There’s a Great Game with Germans and Russians and Brits competing. And the first story starts in 1910.’

***

A print and digital subscription to The Spectator is just $7.99 a month

***

If his Steampunk books take off, all well and good. But Seeger still works on training contracts with US Special Forces and is restoring his period home in East Aurora. In any event he has the aura of someone who has, as one of his SBS characters might say, been there, done that and got the T-shirt.

For his role leading the CIA’s eight-man team Alpha, which fought alongside the Green Berets and the Northern Alliance in 2001, Seeger was awarded the Intelligence Star for Valor, the equivalent of the US military’s Silver Star.

The only public image of Seeger from that time shows him bearded, wearing sunglasses and a lungee turban, sitting on a horse supplied by the legendarily fearsome Afghan warlord general Abdul Rashid Dostum. The jungle boots Seeger’s wearing, issued to him when he was in the 82nd Airborne Division in the early 1980s, are now in the museum inside the CIA’s headquarters.

This article is in The Spectator’s August 2020 US edition.