None of William Shakespeare’s characters are more controversial than Shylock. The moneylender from The Merchant of Venice may be the most famous Jew in Western culture other than Jesus. But what kind of Jew is he? Is he a collage of stereotypes who has been useful to antisemites, including the Nazis? Or does he represent the Jew as cruelly vilified, a tragic victim of persecution?

Shakespeare, who was born 460 years ago today, could never have envisaged the way in which the events of the twentieth century would change the way we look at Shylock. Yet it’s impossible now to watch The Merchant of Venice without thinking of the Holocaust. To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric, Theodor Adorno wrote. Auschwitz has also changed the way in which we think about Shylock.

The Nazis saw Shylock as a useful tool of propaganda

There’s no doubt that the Nazis saw Shylock as a useful tool of propaganda. In 1933, there were more than a dozen productions of the play; another thirty followed over the next five or so years. In 1938, shortly after Kristallnacht, the play was aired over German radio. In 1943, when the Nazis declared Vienna “Judenrein” (free of Jews), the renowned Burgtheater celebrated with a performance of The Merchant of Venice. Shylock was played by Werner Krauss, who had also performed in the notorious Nazi propaganda film Jud Süss (1940). A Viennese newspaper critic described Krauss’s appearance as such:

With a crash and a weird train of shadows, something revoltingly alien and startlingly repulsive crawled across the stage… The pale pink face, surrounded by bright red hair and beard, with its unsteady, cunning little eyes; the greasy caftan with the yellow prayer shawl slung round; the splay-footed, shuffling walk; the foot stamping with rage; the claw-like gestures with the hands; the voice, now bawling, now muttering — all add up to a pathological image of the East European Jewish type, expressing all its inner and outer uncleanliness, emphasizing danger through humor.

The theater critic Siegfried Melchinger saw the play and made the connection clear: “Behind the Jew we can see the wicked man of the fairy tale, the unearthly man-eater, the bogey man, who, just like the witch, will finally have to be shoved into the oven.”

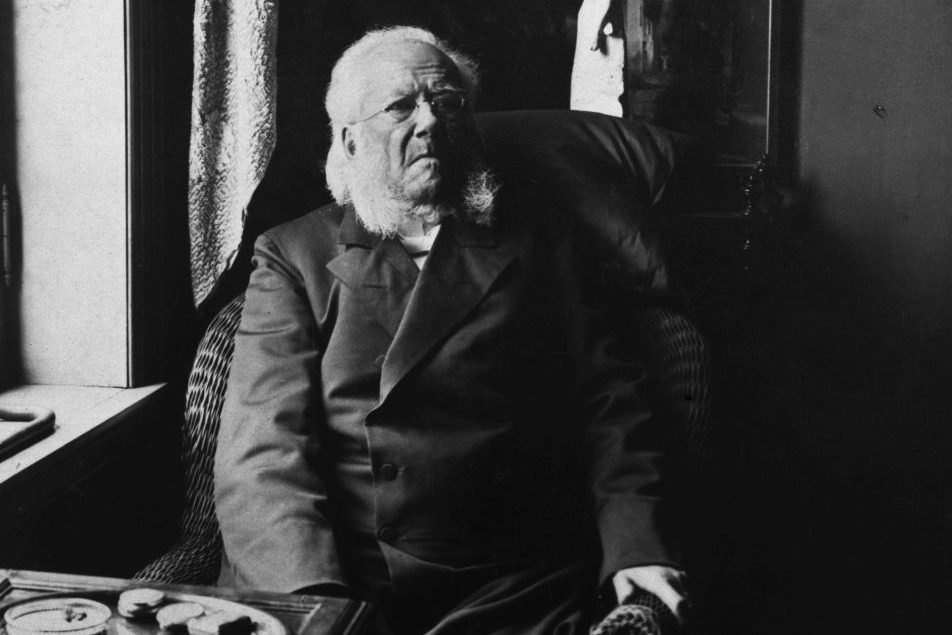

But such foul depictions did not start in Germany in the years during Hitler’s rise to power. Even in the early performances of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, Richard Burbage portrayed Shylock as grotesque, wearing a red wig to associate him with the devil. The emphasis on his Jewishness as the reason for his financial exploitation arose during the debate in England over the Jewish Naturalization Bill of 1753, at a time when the actor Charles Macklin deliberately chose to dress in Jewish costumes in his performances of the character in Drury Lane. Humanizing Shylock only began with two great Shakespearean actors of the nineteenth century, Edmund Kean, who brought dignity to Shylock, and Henry Irving, whose tragic Shylock was an austere, dignified patriarch of the chosen people, seeking vengeance only because he had been abused.

Actors may have started to humanize Shylock, but it was Christian theology that Shakespeare used to shape the plot of the play. A villainous Shylock more concerned about his money than humanity drew from Judas’s betrayal of Jesus for silver. In the play, the character of Portia, proclaiming the virtues of Christian mercy against Jewish pedantry, ultimately used a legalistic argument (“shed thou no blood”) to defeat Shylock, deprive him of the “pound of flesh” he demanded and and punish him without mercy. Through this, Shakespeare was using, but also challenging, Christian stereotypes.

Gotthold Lessing, a leading intellectual of the German Enlightenment known for his philosemitism, wrote the play Nathan the Wise in 1779 as a retort to the antisemitic image of Shylock. Modeled on Lessing’s good friend, the Jewish philosopher Moses Mendelssohn from Berlin, Nathan combines compassion, forgiveness, and generosity with nobility and a powerful intellect. He is not shrewd, like Shylock, but wise. Yet at the end, neither Shylock nor Nathan is left with children who remain Jewish; bad or good, the Jew has no future.

Despite its reputation as antisemitic, the Victorian novelist Maria Edgworth used The Merchant of Venice in her work to overcome negative stereotypes of Jews. In her popular 1817 novel, Harrington, the protagonist attends a London production of The Merchant of Venice where he sees a beautiful woman in a neighboring box shedding tears as she watches tragedy befall Shylock. His dislike of Jews, instilled in him from childhood, is transformed and he falls in love with the woman, a “Jewess.”

In Yiddish productions, Shylock’s fate was tragic, sometimes mitigated by having Jessica return to her father. After the Holocaust, the “pound of flesh” took on new meaning. The great Yiddish actor Maurice Schwartz changed the courtroom scene: Shylock was awarded his bond and raised his knife to carve a pound of flesh from Antonio — then paused, silent, and dropped the knife, calling out, “Ikh ken nit, ikh bin a yid.” Jews don’t kill. The Jewish audience of Holocaust survivors wept.

A sympathetic Shylock was also depicted in productions in apartheid South Africa that identified black Africans with Shylock’s fate. Blacks were persecuted and vilified, their land and culture stolen from them, just as Shylock was dehumanized and left destitute.

A very different reading of the character arose in China, where The Merchant of Venice remains popular and available in several translations. Under Mao and the cultural revolution, the play presented Shylock as a feudal usurer and Antonio as a despicable rising capitalist. More recently, as economic policies shifted, Chinese productions have shown sympathy for the racial and religious oppression Shylock suffered and approval for his capitalist efforts.

The Jewish audience of Holocaust survivors wept

Arab rage over Zionism most dramatically politicized the play. An Arabic translation was first performed in Cairo in 1922, focusing on the monetary rather than religious elements and omitting Shylock’s forced conversion to Christianity. Instead, his usury was equated with Zionism: the demand for a pound of flesh symbolized the Zionist appropriation of Palestine, leaving Arabs to identify with Antonio as victims of the Jews. A 1945 Arabic revision of the play, The New Shylock, portrayed him as a bloodthirsty member of a network of Jews purchasing Arab land as their pound of flesh. The trial scene was a debate over the Balfour Declaration, with Shylock demanding a pound of flesh from Britain.

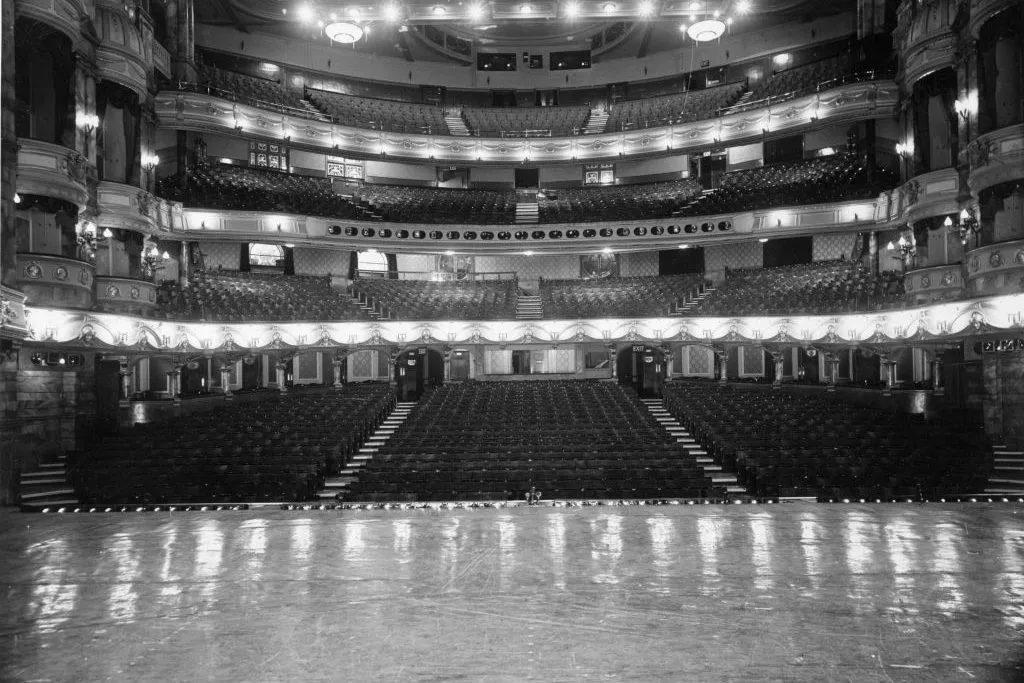

The Merchant of Venice was the first play staged in Hebrew at Tel Aviv’s Habimah Theater in 1936, during the early weeks of the Great Arab Revolt. To derogatory cries of “Hep-Hep” Shylock appeared wearing a yellow badge. He was portrayed as a heroic symbol for Jewish perseverance despite persecution, and his victimization as a rationale for Zionism.

For the Israeli Left, though, Shylock could also represent defeated Arabs. In a famous scene in the 1986 Israeli film Avanti Popolo, set during the 1967 war, Israeli soldiers in the Sinai desert come across two stranded Egyptian soldiers, begging for water. One of the Egyptian soldiers, an actor in civilian life, falls on his knees and recites Shylock’s famous speech, “I am a Jew! Hath not a Jew eyes?” to which the Israeli soldier responds, “He’s got his roles confused.” Both Egyptian and Israeli soldiers, the film argues, are stranded and are at the mercy of politicians.

How does a play inspire both antisemitism and its repudiation? Is Shylock cruel because he is a Jew or do Christian mockery and scorn incite him? Alexander Granach, a great German-Jewish Shakespearean actor of the 1920s and 30s, embraced Shylock as the essence of “spiritual strength and great loneliness.” Karin Coonrod’s 2016 production held in the Venice ghetto had six actors portraying a multifaceted Shylock.

The play has been read both as an indictment of Jews and as a critique of Christian society’s cruelty toward them. Shakespeare’s brilliance is his demand that we refuse binary categories and resist reductions of the play to a narrative of oppressor and victim. Although Shylock’s great speech (“Hath not a Jew eyes”) concerns Jewish bodies, the play focuses on his inner life: his response to being spat, spurned, and cursed by Christian society, and demands our attention to its moral cost to that society. The enigma of Shylock — as stereotype or victim — will continue to endure, hundreds of years after its author died.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply