There is something otherworldly about Rory McEwen’s paintings of plants, leaves and fruit. They are indisputably beautiful, often breathtakingly so, but they are almost eerie in their self-possession. They are like planets vibrating to the music of the spheres — quivering with arrested energy. These images are super-real (rather than surreal) but they sometimes have a surreal edge that can be disturbing.

‘I paint flowers as a way of getting as close as possible to what I perceive as the truth’

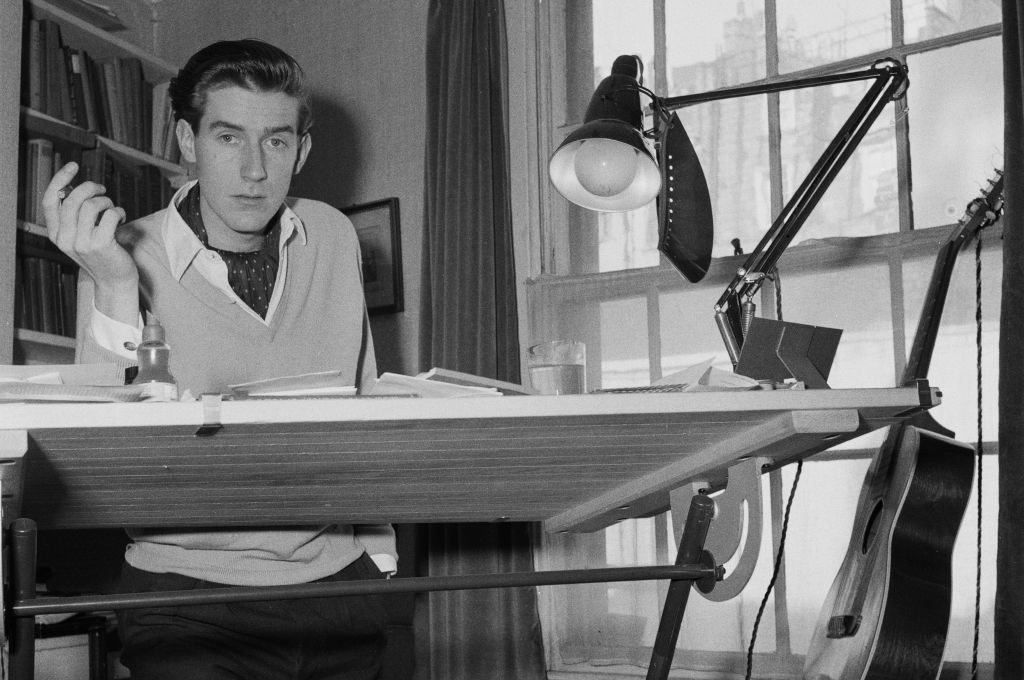

Although best known for painting these botanical watercolors on vellum, McEwen (1932-82) was a man of many parts: an extraordinarily talented figure, a poet and broadcaster, a folk and blues musician as well as, for many, the greatest botanical painter of the past hundred years. His friend Grey Gowrie wrote: “You would need to combine the talents of Proust and John Buchan to describe him.”

McEwen was fourth in a family of seven children, born at Marchmont in the Scottish Borders. He painted flowers from the age of eight, instructed by a French governess. Wilfrid Blunt, author of a seminal history of botanical illustration, taught him at Eton and showed him the great flower painters of the past. McEwen’s great-great-grandfather on his mother’s side was John Lindley, the distinguished botanist, gardener and orchidologist. To this culturally rich heritage he brought his own enquiring mind. Much later he wrote: “I paint flowers as a way of getting as close as possible to what I perceive as the truth, my truth of the time in which I live.”

There have been regular exhibitions of McEwen’s botanical works. The last one I saw was at London’s Kew Gardens a decade ago, which I reviewed in these pages. Since his early death at the age of fifty, McEwen has been celebrated for his botanical paintings, and particularly the late portraits of single leaves. Currently there is an exhibition of his work entitled A New Perspective on Nature on tour in America into next year. The show has already called at Charleston; was at the Davis Museum in Boston until December 15; then moves on to the Society of Four Arts, Palm Beach (February 1-March 30) and later the Driehaus Museum, Chicago (May 17-August 17). McEwen’s paintings are in public and private collections all over the world, and his work is busy making more converts in America. It exerts a perennial appeal.

Although he is most renowned as a painter, McEwen first found fame as a musician. His older brother Jamie was a jazz enthusiast and so Rory encountered as a schoolboy the music of the folk and blues singer Lead Belly. Rory learnt the blues and went in search of a twelve-string guitar (eventually finding one of these scarce instruments in a pawn shop), so that he could play like him. In 1956, he embarked on a road trip across America with his brother Alexander, playing guitar and singing wherever they could. They went on to make two LPs and even appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show.

On his return to Britain McEwen became much sought-after as a guitarist and singer, performing around the country from the Edinburgh Festival to London’s Festival Hall. Soon he was given a regular spot on Tonight, the BBC’s current affairs program presented by Cliff Michelmore, singing topical calypsos written mostly with Bernard Levin. By now he was also The Spectator’s art director, responsible for the magazine’s design and layout, and he and Levin shared an office there.

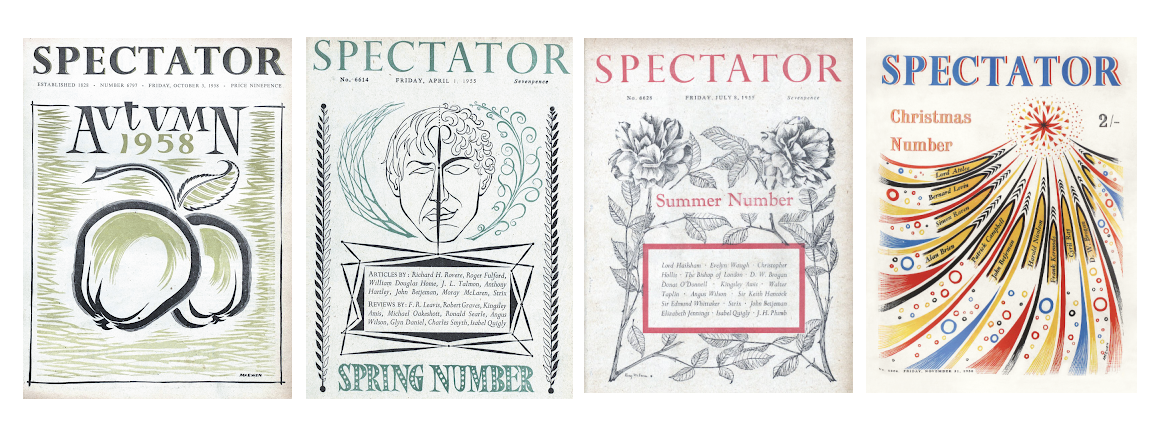

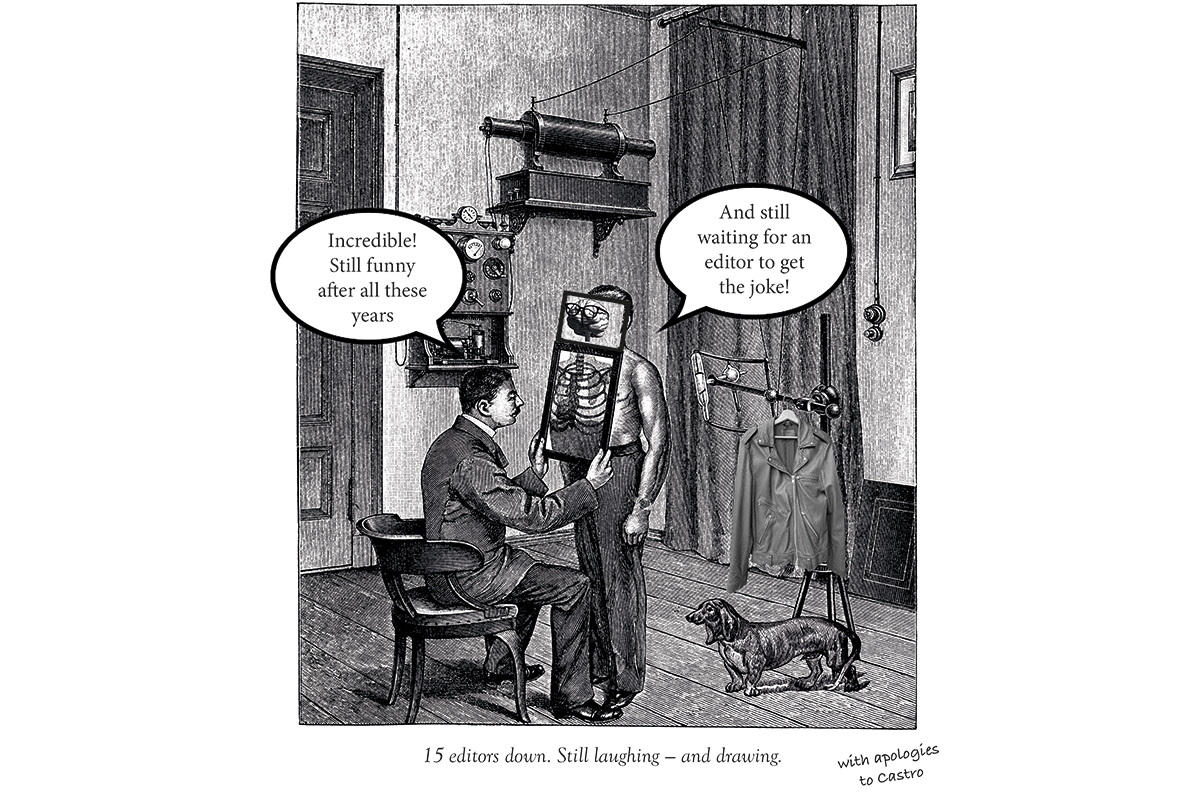

McEwen’s skill as a painter in the sure placing of his images in a large expanse of pure white vellum and his brilliant sense of design made him an excellent choice for art director. Throughout the 1950s, he designed covers for The Spectator: the spring number for 1954 is a simplified Green Man, the spirit of the countryside and symbol of rebirth; for autumn 1958, he contributed a bold and brushy black outline of a pair of apples hanging together, modeled and backgrounded in green, and for Christmas that year, a starburst in red, black, yellow and blue. The McEwen covers that illustrate these pages were almost completely forgotten until they were discovered this year in the archive.

After his success on Tonight, in 1962 McEwen was given his own late-night TV show, Hullabaloo, showcasing folk and blues. He reached an even wider audience, and among those who were transfixed by his playing were Van Morrison and Martin Carthy. Van Morrison puts the case decisively: “He was actually the only person I’ve heard that played twelve-string the same as Lead Belly… he was the only one that could actually do it for real.” Carthy observes: “A lot of people try to tidy Lead Belly up, and he never did, he went at it full throttle.”

Hullabaloo lasted for a couple of years, but McEwen had already begun to ease himself away from the engulfing world of showbiz. Despite being something of a music legend for helping to introduce the blues to the UK, he wanted to get back to painting full-time. In fact, he had never really stopped painting. From Eton he had gone into the army, and after two years in the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders he painted a rose on his first day of freedom. Although he had no formal art school training, he later wrote that his hand “had unknowingly educated itself.” This process continued at Cambridge, where he illustrated a book on carnations and pinks, and indeed throughout his life, as his skills became ever more finely honed. He held his first solo exhibition of paintings in 1962 in New York, and continued to show his work regularly, mostly in London and Edinburgh, with occasional forays to America, Europe and Japan.

In 1958, he married Romana, granddaughter of the poet Hugo von Hofmannsthal. The couple moved to a house in Tregunter Road, Chelsea, which became the hub of McEwen’s active social world, with parties seemingly every night. You might meet John Lennon there, or the Everly Brothers, or witness Ravi Shankar giving George Harrison lessons on the sitar. McEwen was something of a catalyst, bringing people together: famously he introduced Bob Dylan to Robert Graves. He drove a purple Ferrari and was a stylish dresser. He made friends over a broad spectrum and brought a great deal to these relationships. For instance, when he met the American artist Jim Dine in 1965, the inspiration went both ways: Dine encouraged McEwen to take himself seriously as an artist, while acknowledging that McEwen was a formative influence on his own work. Later on, McEwen numbered Cy Twombly and Brice Marden among his friends.

“He was a merry, antic figure, a kind of modern-day Pied Piper,” writes his niece Christian McEwen in her memoir of him, Music Hiding in the Air. “He was both gregarious and private, modest and ambitious; light-hearted and at the same time intensely serious.” She describes him “moving with great sweetness and fluidity among his many selves, somehow able to balance the prankster and the poet, the artist and musician and the family man, the traveler and the much beloved friend.” Another friend, the poet Alastair Reid, said: “He listened with maximum attention to people and he took them in deeply and he reacted. That was the most unforgettable and admirable thing about him, his absolute total attention to anybody, no matter who they were.”

McEwen was ambitious for his art. He always wanted to go beyond the limits of traditional botanical illustration. He wrote: “I want to make landscapes that will have the appearance of giant palettes, huge daubs and blobs of infinitely subtle colors, bumping each other out of the way like clouds blowing across the sky.” He aimed to make monumental sculpture in a modern idiom, and experimented with Corten steel, Perspex and glass. He made abstract paintings and a series of structures from canvas tarpaulins draped over ropes to produce various fold-patterns, a modern take on drapery painting. In 1969, he made a large sculptural wooden construction covered in Harris tweed.

Restless curiosity drove him on and he continued to strive for innovation. Between 1978 and 1980 he painted a well-known series of single leaves in autumnal colors, often diseased or damaged. It seems possible to read into them his own biography: the first cancer diagnosis in 1979 adds poignancy to any interpretation.

As he himself said: “A dying leaf should be able to carry the weight of the world.” These were succeeded by autobiographical collages of cut-up watercolors juxtaposed with photos and handmade paper. In the spring of 1981, he produced forty-five of these in two months, working twelve-hour days. These and the leaf paintings offer a partial account of his life. The pictures of leaves were named after the places he found them and thus constitute something of a travel diary. He wrote of them as being something he had to do, “like a debt I have to pay,” while what he really aspired to was “the distant possibility of making a fine fresh dangerous painting.”

Although McEwen hoped to be remembered for making something “fine fresh [and] dangerous,” his true achievement was in the creation of extraordinary botanical paintings that are both rare and timeless.

Spectator Christmas cards featuring artwork by Rory McEwen are available here.

Leave a Reply