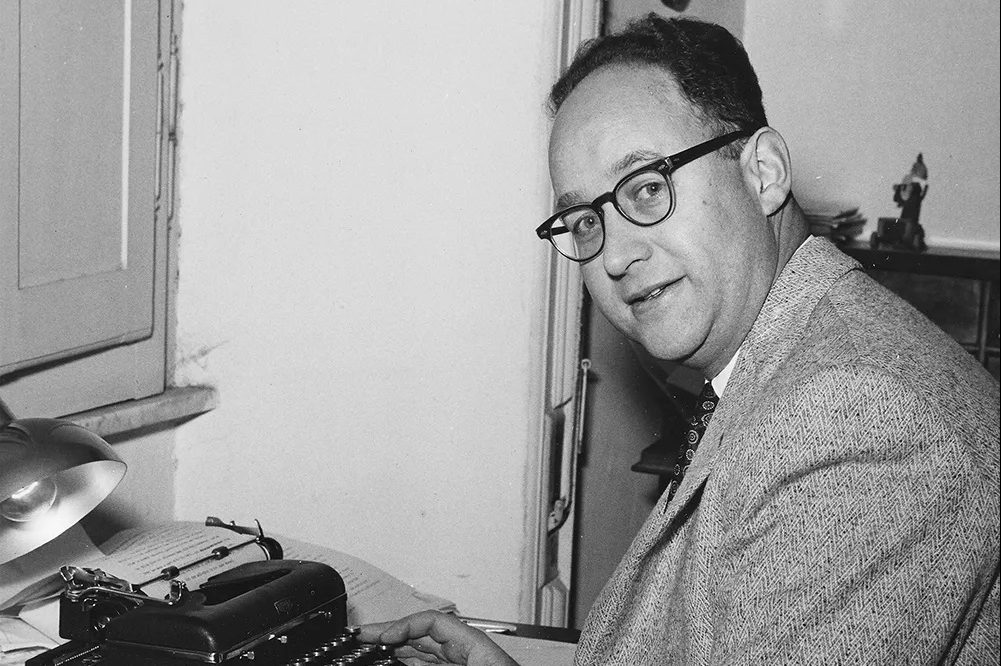

Richard Ellmann’s acclaimed life of James Joyce was published in 1959, with a revised and expanded edition appearing in 1982. The first edition, the work of an ambitious young American academic, received what Ellmann’s editor at Oxford University Press described as “the most ecstatic reaction I have seen to any book I have known anything about.” Ellmann’s work would “fix Joyce’s image for a generation” wrote Frank Kermode in The Spectator, a prediction described by Zachary Leader as “if anything, too cautious.”

By the time of the second edition, Ellmann had become a lionized Oxford don and the image of Joyce he had fixed was starting to chafe. Post-structuralism was now challenging traditional approaches to literature and biography was regarded by English departments as an inferior form of fiction. Nonetheless, it was impossible to ignore or avoid Ellmann’s James Joyce. The road to Joyce was via Ellmann. His magnum opus had contributed to what one reviewer described as a “critical and methodological paralysis” in Joyce studies.

Ellmann’s Joyce is a wise, balanced and utterly compelling biography of the “masterpiece” that ignited Joyce studies and introduced the Irish modernist to the general reader. It is also an account of pre- and post-war English departments, a golden age of academic brilliance and a rare moment when biography, at its best, was considered an art form. In addition to outlining the construction of James Joyce, Leader discusses its impact, weighs up its legacy, quotes generously from its strongest and weakest passages and mounts a defense of Ellmann’s interpretative methods.

Ulysses, according to Ellmann, was a work of autobiography. Every character had a flesh and blood original, and everything said or thought by Leopold Bloom on Thursday June 16, 1904, had been said or thought by Joyce himself. “The life of the mind, so far as Joyce himself led it, is allowed to amount to very little,” concluded Ellmann’s enemy Hugh Kenner. It was Ellmann who “authorized the bad habit” of blending life and art, wrote Denis Donoghue. “He made it respectable for lesser biographers to assume… that if something is in the novels it must have happened.”

Leader’s sources come from the Richard Ellmann Papers at the University of Tulsa, 450 boxes of notes, drafts, manuscripts and correspondence, including a lifetime of letters to and from Ellmann’s parents detailing every personal and professional decision he ever made. To cut a swathe through this forest and balance the focus, Leader divides his book into two halves. In the first, “The Biographer,” he explores “the sort of person Ellmann was, and how he came to be such a person,” tracking his progress up to the age of 34, when the research for James Joyce began.

Ellmann was born in Highland Park, Michigan, in 1918. His father’s family were Jews from Romania and his mother’s were Jews from Ukraine. He married a Catholic and had no attachment to his family faith. There was never any question, however, given the scale of his parents’ ambitions for him and determination to interfere in every aspect of his life, that “Dick” would succeed at whatever he chose to do. After graduating from high school “fourth in a class of 326, with an average school grade of 98 out of 100” (Leader, like Ellmann, homes in on the details), he studied English literature at Yale, published his poetry in leading magazines, and worked at the Office of the Coordination of Information during the war.

He was at his happiest when snowed under by letters, notes, drafts, diaries and transcripts of interviews, and it was the indexing and classifying of secret documents that taught Ellmann the skills he would need in the Joyce archives. During a wartime visit to Dublin, he introduced himself to W.B. Yeats’s widow, who gave him access to the treasure trove of papers which allowed him, aged 30, to turn his PhD into his first book, Yeats: The Man and the Masks. These same personal skills later earned him the trust of the Joyce family. After a brief spell at Harvard, Ellmann took a job in the English department at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, where he stayed for the next 17 years. Here, as the departmental star, he was given the time and funding to begin his work on Joyce.

In part two, “The Biography,” Leader describes the making of the book. “I am endeavoring to treat Joyce’s life with some of the same fullness that he treats Bloom’s life,” Ellmann explained to a colleague. “The initial and determining act of judgment in Joyce’s work,” he argued, “is the justification of the commonplace.” In emulation of his subject, Ellmann “minutely documented,” as Leader puts it, “Joyce’s everyday activities and routines.” His ability to enter his subject’s mind on an ordinary afternoon was, for most of Ellmann’s readers, a sign of his brilliance. But Kenner was less impressed: “Much energy has gone into chronicling the shillings various men lent Joyce, how many, on what date, and whether they were repaid.’

For writers without the backing of a university, Ellmann might come across as pampered and indulged. Where in his story is the struggle, the self-doubt, the despair at not finding a publisher? Getting ahead, however, was not always as easy as it looked. Ellmann was Jewish for starters, and drawn to 20th-century literature when the Harvard and Yale curricula stopped with the Victorians. Plus he had monster parents breathing down his neck and Kenner snapping at his ankles. Despite being an outsider with an interest in rogue literature, Ellmann nevertheless wrote the books he wanted to write with maximum support from literary estates and a lifetime’s supply of research grants, fellowships, awards, pay rises and promotions. No sooner had he delivered James Joyce than he was handed a year’s paid holiday to recover from his labours.

It was his wife, Mary, also a Yale graduate (her PhD was on Tennyson), who needed the holiday. In 1956, while Ellmann was following Joyce’s footsteps in Europe, Mary – the real genius of the couple, according to their daughters – was at home with the toddlers. “I will never again live in this house by myself,” she wrote to her husband. Pregnant during a summer of staggering heat, after putting the children to bed she trawled through Ellmann’s mountain of post:

I cannot bear it. I feel myself being destroyed… I live in constant horrified contemplation of my own life. I am half sick, alone and burdened with stupid, monotonous work.

Ellmann’s response was to extend his stay abroad.

Mary’s letters take us to the heart of women’s lives in the 1950s. It wasn’t until 1969, when her eldest child had left home, that she wrote her own masterpiece, a brilliantly witty and furious diatribe against female stereotypes called Thinking About Women. No sooner had her book appeared than Ellmann was offered an Oxford professorship. Mary and their daughters wanted to stay in America, but Ellmann was not thinking about women. Being in England would make the research for his next biography, a life of Oscar Wilde, easier. Mary now ruptured a blood vessel in her brain which left her paralyzed down her left side and wheelchair-bound for the rest of her life. ‘It is sometimes said that stress can bring on an aneurism,” Leader drily comments.

When it came to Joyce’s own selfishness and neglect of his family, Ellmann gave his subject an easy ride. It was as if, says the Irish scholar Declan Kiberd, he agreed with Dr. Johnson that “a good artist cannot be a bad man.” Leader has no such illusions about Ellmann, a writer driven, like Joyce, by rocket-fueled ambition and steely self-belief. It is the biography he has come to praise, not the biographer. Despite being seen by his parents as “tender minded” and “fragile,” Ellmann evolved, as Leader elegantly puts it, “from a mild man” to “a man with a mild manner.” Ellmann’s Joyce is a powerful portrait of the man, and also the masks.

Leave a Reply