In the years before the French Revolution saw heads roll down the boulevards, revolutionaries murdered in the bath, and endless numbers of fluffy lap dogs forced to fend for themselves after their mamans met their untimely ends, one art critic made his name with his fearless criticism of Paris’s annual art exhibition, the “Salon.”

The prominent style in mid- and late-eighteenth century France was Rococo — think impossibly ornate, gold-swirled furniture; paintings of pink, fluffy nymphs in gilt-edged, asymmetrical frames; and portraits of women in dresses so large, and so embellished, that they resemble iced wedding cakes more than human beings. In the face of endless walls of this style of art, the critic Denis Diderot was caustic.

With a brilliant turn of wit, he asked the readers of his 1765 summation “not to assume” the paintings he discusses are “simply bad.” They are, instead, “positively detestable.” He claims that one artist, Charles-Michel-Ange Challe, “mortally wounded” his eyes. On seeing a different painting, he questions how the canvas “got into the Academy.” He declares that yet another artist’s work represents a “degradation of taste, color, composition, character, expression, and drawing.” “What can be in the imagination of a man who spends his life with prostitutes of the basest kind?” he asks.

If Diderot was Rococo’s most scathing critic, the artist he reserved his harshest lines for (“I have seen enough of bosoms and buttocks”), was François Boucher. For Diderot, this painter of idealized rustic scenes, classical nymphs, and expanses and expanses of creamy-pale female flesh was the absolute nadir of everything he disliked about the Rococo: “I don’t know what to say about this man,” he huffed.

Diderot died in 1784, but it’s tempting to imagine what his pen might have stretched to had he lived a century longer, to see the French Impressionist Berthe Morisot begin to exhibit her works. Or, if in a feat of necromancy or incredible longevity, he had been alive to see the expertly-curated exhibition of her works alongside her eighteenth-century counterparts — Boucher, Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, Jean-Honoré Fragonard and Antoine Watteau — at London’s Dulwich Picture Gallery.

The first show of Morisot’s work in the UK since 1950 opens with a room full of her paintings, including canvases lent from across Europe for the occasion. Her 1885 self-portrait — all rapid brushwork, bare canvas, and daubs of paint which give the impression that the portrait is still somehow inside her palette — sits up against “Summer’s Day” (1879), a portrait of two straw-hatted women, sitting in a boat in the middle of a perfectly blue-green lake. “In the Bois de Boulogne” (1879) — a picture of the same two women from the boat, this time picking flowers in the park — hangs near “Girl on a Divan” (1885), an interior portrait which, nevertheless, has a similar vitality and palette: Morisot has painted horizontal and diagonal brushes of yellow and blue across the girl’s white dress, as if they were somehow racing and moving across the fabric.

Morisot was the only woman who exhibited with the Impressionists from their first breakaway exhibition in 1874; she would, in later years, be joined by Marie Bracquemond and the American artist Mary Cassatt. She continued to be a part of the group — organizing exhibitions, socializing with other artists and holding weekly artistic salons, not unlike a French version of the Bloomsbury group — until her death in 1895. And as the Dulwich show reveals, she was a brilliant painter of women’s lives. Her subjects sit in moments of introspection, lie on sofas on the edges of social interaction, or stare at themselves in mirrors, trying to puzzle out something just beyond what the viewer can see.

Why, then, does this exhibition place her in dialogue with eighteenth-century art — with its idealized women and depictions of high society?

After the Revolution, eighteenth-century French art was seen as almost indivisible from the ancien régime — with its brioche, its faux-rustic cotton dresses, its excess — it had depicted (in a delicious twist of irony, Diderot too was condemned by the revolution for his “excessive” atheism). Paintings by Fragonard, Watteau and Boucher weren’t collected by individuals or institutions, or written about in books or journals, until the 1830s when finally the spectre of the Revolution began to fade. Inspired in part by the Goncourt brothers — the diarists and authors Jules and Edmond — whose twelve-part French Painters of the Eighteenth Century began to appear in 1859, and a small group of collectors who filled their houses with works by the artists Diderot had so vehemently attacked, a new interest in eighteenth-century art began to grow.

For Morisot — born in 1841 and traditionally trained by copying in the Louvre — seeing these works in private and public collections (and, in 1860, at a major exhibition at the Galerie Martinet), would have been her only way of experiencing the art that was so captivating Paris. Unlike two other women who would later be involved in the Impressionist movement — Eva Gonzalès, who is now unfortunately remembered only as Manet’s pupil, and Cassatt — she did not train with Charles Joshua Chaplin, whose portraits of women cradling doves and blowing bubbles were little more than the eighteenth-century warmed up.

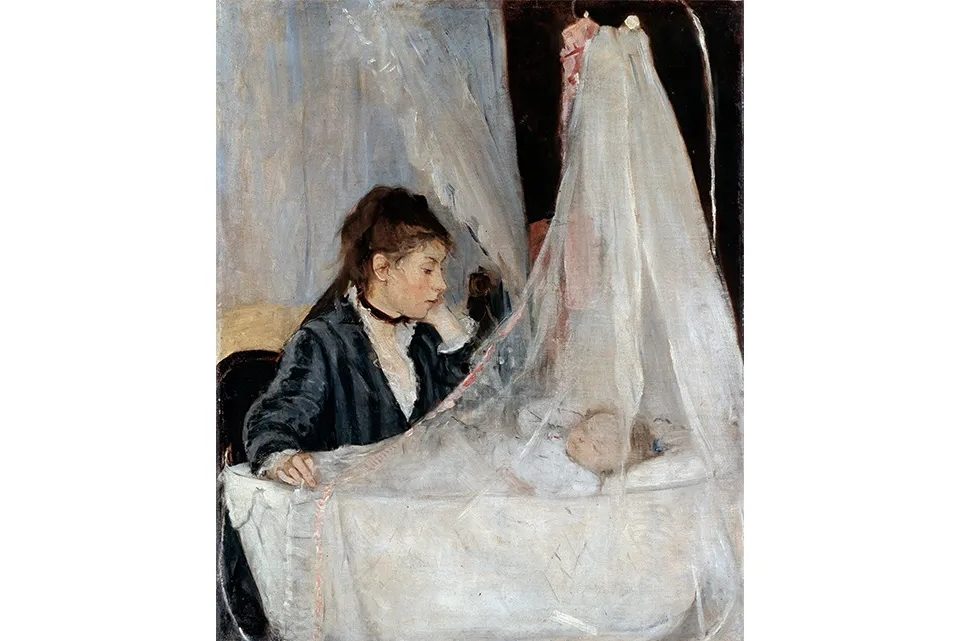

But Morisot’s link to the 18th century is undeniable. In the Dulwich exhibition, next to Boucher’s “Young Woman Sleeping” (c.1760) — a girl lying back with a face of passive near-ecstasy, her breasts bared by a nightgown that has made no effort to contain them — sits Morisot’s Resting (1892). The composition is the same: a woman, at the center of the canvas, with her head tilted to one side and her eyes closed. But it’s hard to imagine Diderot criticizing the second painting in his favorite terms: in the place of Boucher’s idealism and voyeurism, Morisot’s painting is one of touching intimacy. The girl is asleep, still, and has her breasts bared, but it appears more a moment of stillness and domesticity than as if she’s a hyper-sexualized nymph or cherub.

Morisot would have seen works by Boucher, Fragonard, and Watteau in France — and, when she visited London on her honeymoon in 1875 (after her marriage to Eugène Manet, the more famous artist’s brother) she saw a host of eighteenth-century works by the likes of Thomas Gainsborough, Joshua Reynolds, and George Romney. In her letters back to her sister and fellow artist, Edma, she wrote that she had “a great desire to become thoroughly acquainted with English painting.”

From the 1870s onwards, Morisot’s dance with the eighteenth century is visible across her canvases. In 1875, she painted “At the Ball” — a woman is sitting to one side of the festivities, holding an eighteenth-century fan up to her face. In 1876, she worked on “Young Woman Watering a Shrub,” which, as the curators at Dulwich suggest, seems to have taken elements of Watteau’s compositions of elegant women and men and applied them to a girl holding a watering can on a gray terrace in Paris.

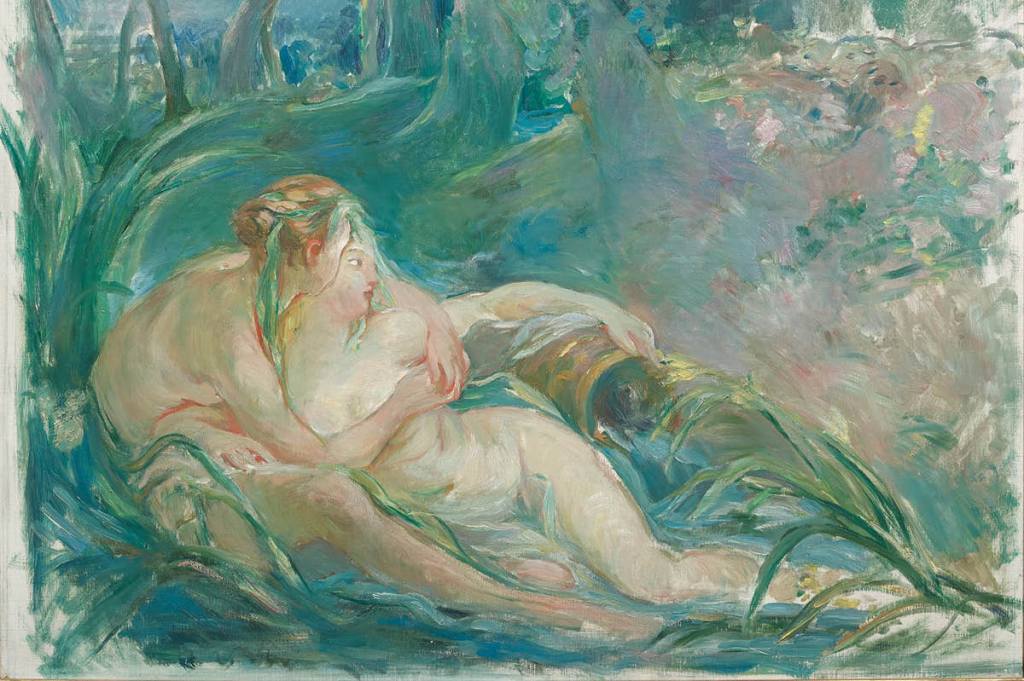

In later years, she made this interest more overt. Her large, pulsating canvas “Two Nymphs” (1892) shows two Rubenesque women lying with their limbs wrapped around each other and foliage, mirroring them, wrapped around the canvas. It’s an image which seems to move and spin the more you look at it, as pale flesh curls into swipes of green and foliage folds in on the bodies. It’s a bold composition, but it isn’t entirely original: Morisot has focused in on the furthest left-hand corner of Boucher’s 1750 work, “Apollo Revealing His Divinity to the Shepherdess Issé.” In Morisot’s work, though, there is no Apollo taking off his human disguise; nor is there a shepherdess with her arms stretched wide and her breasts bared to welcome him. There are no clusters of nude cherubs, and no bright shafts of light to suggest divinity. Instead, Morisot has taken a moment of mythology and created a painting that seems to be about women’s interactions with each other; about movement and physical touch. In her version, it isn’t even clear that there is a world beyond the canvas. One of the nymphs is looking rightward, but her gaze implies nothing more than elegant disinterest.

This isn’t the only work in the exhibition which was born out of a direct engagement with Boucher’s work. Ten years earlier, she had painted a pastel-colored canvas “Venus asking Vulcan for Arms” (1883-84), zooming in on a detail from Boucher’s work of the same name. Here, Morisot has taken another moment of mythology — the moment Venus asks for a suit of armor for her son, Aeneas, before he goes to war — and again, made it about something much more intimate and specific. In her painting, two nymphs are perched in the clouds, with one looking up toward the top left, the other down where her hand touches her thigh.

More of a “study” than a complete work like the other Boucher copy, this is still a scene which has been altered in being removed from its original content. Instead of pure mythology, Morisot is working with the textures of flesh, and exploring how limbs sit in contact with each other.

But the link between Morisot and Boucher — and other eighteenth-century art — is hardly a one-way tale of influence. Morisot is in dialogue with these older works, changing them in her new-found Impressionist style.

When I talk to Lois Oliver, the curator of the Dulwich exhibition, she is keen to stress that there is something “very introspective and not at all flirtatious” about Morisot’s paintings, despite the grand scenes she has often borrowed them from. And, in the face of such huge, dramatic subjects, she has chosen “those peripheral characters” from the edges of the original paintings. Like her focus on the woman sitting out at balls, rather than the main event, or her paintings of the most mundane aspects of domestic life, Morisot captures the “smallest thing”: “there’s a real poignancy and importance to that,” notes Oliver.

This focus on introspection and intimacy is a commonplace in criticism of Morisot: she painted women and children, domestic scenes, and fleeting moments of everyday life. In one of her most famous paintings, “Psyche” (1876), a woman stands alone, and stares into a mirror at her dress: the solitude and stillness is all but palpable. But Oliver notes that this is more than just a vision of self-contemplation. It was “quite strategic” as a choice; it appealed to collectors of eighteenth-century art, and she knew it would sell to the “male art buyers.” Morisot was right: it was, in fact, bought by the noted aficionados the Dutuit brothers and, presumably, then placed into the hefty frame in which it still sits today.

During Morisot’s lifetime, she was often saddled with criticism that linked her to the eighteenth century in the most patronizing, sexist way possible. According to critics, she “handles the palette and the brush with a truly surprising delicacy” which hasn’t been seen “since the eighteenth century” and paints from a “palette of crushed flower petals.” In the years after her death, a spurious and persistent rumor emerged that she was genuinely related to the eighteenth-century master Fragonard; as if she could only have a spot in the canon of art history through family inheritance, rather than talent.

But here, in the meticulously curated galleries at Dulwich — complete with Morisot’s letters and diary entries — is a new way of seeing her, and the movement of which she was part. Morisot was deeply engaged with eighteenth-century art history, but channeled this interest into her own style and her own preoccupations. In doing so, she provides a new lens to look at Impressionism: rather than the complete “break” with the past it is often remembered as, this exhibition at Dulwich reveals its links to a rich and divisive art history.

This article is taken from The Spectator’s June 2023 World edition.