‘This is the West, Sir,’ says a reporter in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. ‘When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.’ This is very much the advice that has applied to Calamity Jane over the years. She was the lover of ‘Wild Bill’ Hickok, avenged herself on his killer and bore his secret love-child. She rode as a female army scout and served with Custer. She saved a runaway stagecoach from a Cheyenne war party and rode it safely into Deadwood. She earned her nickname after hauling one General Egan to safety after he was unhorsed in an ambush. She was a crack shot, a nurse to the wounded, a bullwhacker and an elite Pony Express courier.

Not one of these things is true. In fact, as Karen Jones sets out dismayingly early in her book, the only things that the real-life ‘Calamity Jane’ can with confidence be said to have in common with her legend is that she wore pants, swore like a sailor and was drunk all the time. Martha Jane Canary spent most of her itinerant life in grim poverty and hopelessly addicted to alcohol. She worked not as an army scout but as a camp-follower, laundress, saloon girl and occasional prostitute. As one 20th-century biographer put it crisply, her true story is ‘an account of an uneventful daily life interrupted by drinking binges’.

Karen Jones’s book, then, is a sort of dual biography: it’s the biography of Martha Canary (who checks out halfway through this book in 1903, at 47, from alcohol-induced inflammation of the bowels), and it’s the biography of the legend that grew up around her, much of it during her own lifetime and with her encouragement and collusion, and how it changed over the years that followed. She was, writes Jones, a ‘multi-purpose frontier artifact’.

The main point that Jones makes, and makes rather a lot, is that by dressing like a man and drinking in saloons and swearing and shooting things (aka ‘female masculinity’) Martha disrupted the ‘normative feminine behavior’ of the Old West. Non-academic readers might be warned that there’s a good deal of social studies jargon woven through this story. Jones is forever going on about normativity and gender performance and ‘the frontier imaginary’ (in an apt piece of linguistic cross-dressing, ‘frontier’ here serves as an adjective and ‘imaginary’ as a noun). But the material is all here, and very interesting material it is, too. There can be pretty much no reference to Calamity Jane that this diligent researcher does not find space to note: the Beano character ‘Calamity James’; My Little Pony’s ‘Calamity Mane’; ‘“Calamity” Jane Kennedy’ in the Devon-set BBC comedy drama The Coroner; and even — I was impressed by this — a trash-removal company in Margate that ‘sports an advertising insignia of a horse-drawn stage and a name founded on a stupendous use of badinage: WhipCrapAway’.

The ‘poverty-bound drifter who struggled with a drink problem’ became the seed grit around which a great pearl of folklore grew. During her life and after, as Jones ably demonstrates, she went from being a talked-about local character to a regional and then a national archetype, and written accounts (including her own, set out in the mostly fictional 1896 Life and Adventures of Calamity Jane, by Herself) competed to present the ‘real Calamity Jane’ as a token of frontier authenticity. Myth-busting and myth-making went hand in hand.

An early biographer described Calamity Jane at 20, for instance, responding to an inquiry from a passer-by about her underwear: ‘filled the air with shrill and slightly obscene rebukes for his bawdiness, and his sombrero with warning bullets’. An 1878 account put it that:

‘Calamity Jane can throw an oyster-can into the air and put two bullet-holes into it from her revolver before it reaches the ground, and offers to bet she can knock a fly off an ox’s ear with a 16-foot whip-lash three times out of five.’

In 1875, a newspaper reported:

‘”Calamity” has the reputation of being a better horseback rider, mule- and bull-whacker and a more unctuous coiner of English, and not the Queen’s pure, either, than any man in the command.’

Twentieth-century representations (at least until the TV series Deadwood made her into a butch lesbian) tended to present her as a rather feminine cross-dresser, just a crack of the whip away from being Doris Day in her scanties. That was, as Jones sees it, part of an attempt to tame the wild west and fold its more challenging figures into a conservative scheme of sexual stereotypes, where a tender heart beat under the buckskin and the love of Wild Bill (whom in reality Canary knew only for a couple of months) was all that was needed to bring her back into the corral.

Unlike cute little sharpshooting Annie Oakley, the real Calamity Jane was a pretty butch figure (though she married and had a child, so seems to have been straight). ‘The statement that she is prepossessing in appearance is the merest balderdash,’ said the Black Hills Daily Times, ungallantly. ‘She looks more like the result of the gable end of a fire proof and a Sioux Injun than anything we can think of at the present writing.’ An adviser to Cecil B. DeMille (who included Calamity Jane in The Plainsman), cheerily admitted that the film was:

‘complete nonsense from a historical standpoint…the real Calamity Jane was a vulgar, tobacco-chewing, raw-boned kid who resembled nothing more alluring than an oversized Huckleberry Finn, minus the charm of innocence.’

A 1953 account opened by calling her ‘a disreputable old harridan’. (This is what Jones calls ‘a useful insight into the contours of gender containment’.)

Her early appearances in the real historical record are patchy. In 1876 she was arrested in Cheyenne under the pseudonym ‘Maggie Smith’ for stealing clothes off a washing line. After three weeks in jail she appeared in court in a frock she’d borrowed from the deputy sheriff’s wife, the jury let her off (‘testament to the affection with which she was held in local circles’) and she headed for the pub. With ‘frequent and liberal potations’ having ‘completely befogged her not very clear brain’, she commandeered a horse and buggy and made for Fort Laramie, stopping en route at Chugwater Ranch for more ‘bug juice’. There’s a good deal of frontier color in even the true-life accounts. Here’s a world in which ‘competitive buffalo dung collection’ was a popular game for children, and where one ‘Dora Du Fran’ could be madam of a Deadwood brothel called ‘Diddlin’ Dora’s’.

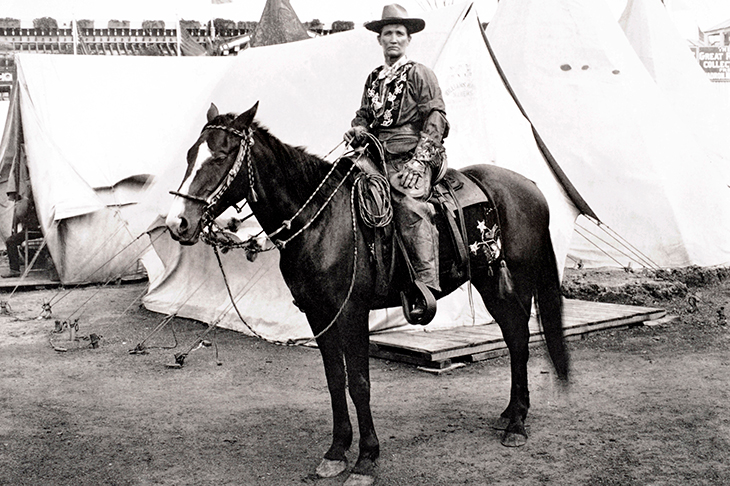

Martha Canary colluded in her own myth, for fun and profit — though didn’t get much of either by the sound of it. At one point she scraped a living hawking copies of her own book door to door. She posed for pictures and sold postcards of herself in her buckskin get-up. She played herself on stage, and was even brought east for the Pan-American Exposition in 1901 by a philanthropist-entrepreneur. But her ‘resistance to her chaperone’s demand for temperance on the train’ set the tone for her New York adventure, and not long afterwards she spent a night in jail after being picked up drunk, borrowed some money from Buffalo Bill Cody and legged it west again.

She claimed to reporters that she’d been engaged to Wild Bill Hickok, and just a month before she died was photographed paying her respects at his grave in Deadwood. The shoot was arranged by ‘liquor-store owner and photography buff John Mayo’:

‘On the day of the shoot, Mayo recalled, Calamity Jane was found sitting on a keg behind the Deadwood bar. After stumbling along the track to the cemetery, and nearly tumbling into the adjacent gulch on several occasions, she promptly fell asleep at the gravesite. Mayo woke her up, thrust into her had an artificial flower (what she called a “phony rose”) to place on Bill’s grave, and set up his camera.’

In due course, she too was buried there as had been — it was claimed — her deathbed wish. A cowpuncher called ‘Teddy “Blue” Abbott’ later claimed she told him when they were drinking together: ‘I hope they lay me alongside Bill Hickok when I die.’ Jones notes drily: ‘It is also possible that the Society of Black Hills Pioneers had a hand in the plan, mindful of the tourist potential of creating a pantheon of buried frontier heroes.’

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.