When musicians from outside the Anglo-American pop mainstream achieve success in the West, there are conflicting reactions. Seun Kuti, the Afrobeat star, once complained to me that most world music celebrities are people who play much the same music as their peers to much the same standard and simply get lucky when a record company stumbles across them.

In some cases, musicians from Asia and Africa have to be rocketed into orbit by the boost of an association with a pop giant, even if they then drop away: thus Ladysmith Black Mambazo with Paul Simon, or Buena Vista Social Club with Ry Cooder. Another explanation is offered by the Alchian-Allen theorem, which suggests that goods exported across borders tend to be of higher quality than domestic ones. If that holds for intangibles such as music, then the explanation for the success of world musicians is that they are, simply, better.

Bear such theories in mind when thinking about Ravi Shankar. He would have been 100 this year. The 92 years he lived, as Oliver Craske’s biography recounts, saw him enjoy not only a second act but many after that. Read as a whole, this book feels like an Indian version of A Dance to the Music of Time: the same characters bumping into each other over the course of nearly a century, relationships fraying and re-knitting, love affairs flaring, dying down, re-igniting, children repeating the mistakes of their parents, all against a backdrop of war and famine and independence and nationalism.

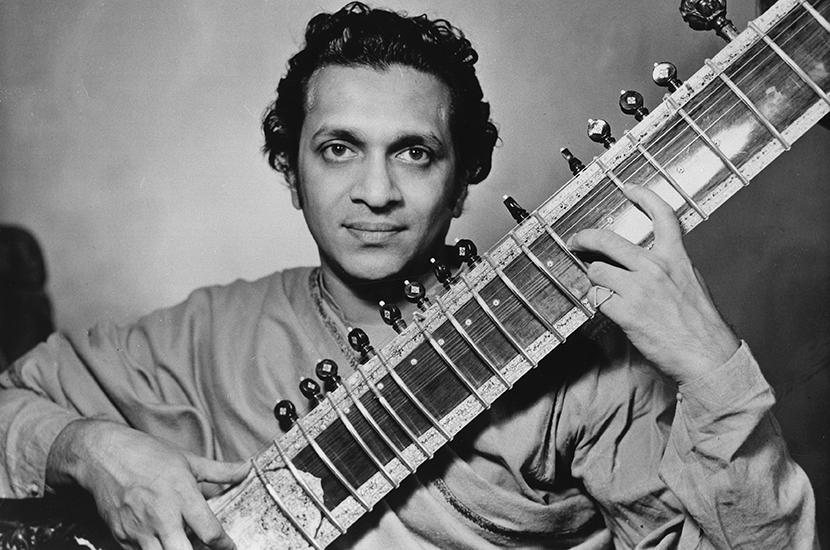

Its hero was born Robu Shankar, to a family headed by a prosperous but largely absent Bengal lawyer. (So absent, in fact, that Robu was born after his father had left his mother for a second wife.) At an early age he joined the artistic troupe of his older brother Uday as a dancer. When Shankar was 15 his father was killed in mysterious circumstances in London. At 19 he changed his name from the Bengali Robu to the Hindu Ravi, meaning the Sun, and took up the sitar. Before he was out of his teens, he had already toured Europe, from the collapsing Weimar Republic to ‘foggy, grimy and depressing’ London, and on to Hollywood and dancing at the Cotton Club.

After the war, he went back to touring. In the mid 1950s he returned to London, finding it much improved, and an American trip saw him build receptive audiences — at first, as Craske relates, among open-eared jazz fans. He toured the USSR in the thaw after the death of Stalin. He recorded with musicians from the West, including Yehudi Menuhin, whom he had first met at the Exposition Coloniale in Paris in 1930, and with those from the Far East — making an early fusion album with the cream of Japanese traditional players. He also established himself as a composer for India’s fast expanding film industry, notably for Satyajit Ray’s Apu trilogy.

In the mid 1960s, he became an unlikely guru for both Philip Glass and, more famously, George Harrison. The Beatle had already bought a cheap sitar and deployed it in rudimentary fashion on ‘Norwegian Wood’. Shankar took him in hand, giving him sitar lessons in Esher and inviting him to India.

Harrison returned the favor, showcasing Shankar at Madison Square Garden at the Concert for Bangladesh (‘If you enjoyed the tuning so much,’ Shankar told the crowd applauding what they took to be his opening number, ‘I hope you will enjoy the playing more’), recording albums at his own home and enlisting him for a traveling revue in 1974. But this did not go well: audiences who craved Beatles hits and were frustrated by hearing mostly solo songs, greeted Shankar’s band with hostility. From then on he distanced himself from rock music and worked to reinforce his status as a classical composer.

Success abroad elicited a mixture of pride and criticism at home. But by the time Shankar died in 2012, his status as national hero was unassailable. The president paid tribute, parliament stood in silence, and thousands massed in Nehru Park.

Indian Sun is a hefty book, but it moves lightly. Craske worked with Shankar on his second autobiography in English, Raga Mala, and this is very much an authorized take, including lengthy quotes from Shankar’s family and friends. But Craske recounts fairly the criticisms of Shankar in his own country, and his sometimes strained relationships with other musicians.

He also explores his complicated and extensive love life in detail. In this he has been helped by access to two decades of correspondence between Shankar and Kamala Chakravarty. Their affair only came to an end when Shankar took up simultaneously with Sue Jones (with whom he fathered Norah, now a country-jazz superstar) and Sukanya Rajan (with whom he fathered Anoushka, a sitar virtuoso and composer).

It would be wrong to conclude that Shankar was merely lucky, or that his success was due to his western admirers. The central insight of Indian Sun is just how hard he worked, scarcely taking a break from the age of 10 onwards. When he stayed for a week with the Swedish director Arne Sucksdorff at a lakeside mansion, he spent the time practicing his sitar for eight hours a day.

Because he largely improvised live, he was able to record prodigiously, releasing 12 albums in the US in 1967 alone. And he was both deep and broad — painstakingly immersed in the classical Indian tradition and yet curious and hungry to collaborate with rock and classical and jazz musicians all over the world. The only point of reincarnation, he said, would be to ‘come back as a better musician’.

This article was originally published in

The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.