‘What a loss is the excellent Humboldt. You and Berlin will both miss him greatly,’ Prince Albert wrote to his much-beloved daughter Vicky, Crown Princess of Prussia, on news of the death of the author, explorer and celebrity Alexander von Humboldt in 1859. ‘People of this kind do not grow upon every bush [‘an den Blumen’] and they are the grace and glory of a country and a century.’

After some delays and bad luck, the grace and glory of the Humboldt name flourishes once again with the opening of the Humboldt Forum. Annoyingly digital to begin with, the launch in January of the Forum signaled the culmination of Berlin’s Museum Island restoration program and, with it, the crowning of the capital’s place within contemporary European culture. Artistic, edgy, studio Berlin finally has a modern museum infrastructure worthy of its creative class.

Yet this otherwise triumphant tale of urban reinvention now has to wrestle with the challenge of reviving an Enlightenment project amid calls for ‘decolonization’ and deep self-doubt about any testaments to European cultural prowess. At South Kensington, we are watching developments closely as the Victoria & Albert Museum owes a profound debt — thanks to Prince Albert — to the Humboldt brothers and their philosophy of Bildung (‘self-formation’).

Alexander von Humboldt was a superstar of the romantic epoch: his travels to Chile and Peru, Mexico and Venezuela, America and Russia ensured the naming of rivers, geysers, mountain ranges, even ocean currents in his honor. He united anthropological interests with the capture of new data on climate, geography and botany. His was a relentlessly inquiring mind.

‘The empirical sciences are never complete,’ he wrote at the age of 76. ‘No generation will ever be able to boast that they have grasped the totality of all phenomena.’ But he was always happy to share his own learning and, on his return to Berlin, he delivered a series of 62 public lectures (open to women as well as men) showcasing his discoveries.

This strongly democratic conception of public education was equally elemental to his brother Wilhelm von Humboldt’s thinking. Indeed, Alexander delivered his lectures at the university that Wilhelm had persuaded the Prussian king Friedrich Wilhelm III to found in 1810 and where Hegel held the chair of philosophy. The University of Berlin embodied the ‘Humboldtian’ model of a holistic education, which disavowed the classical focus of Oxford and Cambridge for a broader curriculum of art and science in which ‘learning to learn’ was the goal. He went on to reshape the Prussian school system premised around the conviction that ‘the education of the individual requires his incorporation into society’. Wilhelm von Humboldt’s ideal of self-learning united natural history and ethnography with art, philosophy and, of particular interest to him, linguistic formation.

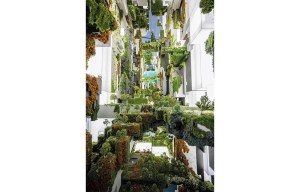

The architecture of Hohenzollern Berlin evolved around this progressive Humboldtian ideal. Envious of Ludwig I of Bavaria’s art galleries and exhibition halls in Munich, the Altes Museum was commissioned for paintings, classical sculpture and casts, to be built by Karl Friedrich Schinkel. In 1841 Friedrich Wilhelm IV decreed that the entire island behind the museum should become a ‘Freistatte für Kunst und Wissenschaft’ (‘sanctuary for art and scientific learning’). And in 1850 the Neues Museum arrived on the island to house art and ethnographic exhibits from around the world, with collections drawn from Alexander von Humboldt and their presentation shaped by his universalist view of the world’s cultures.

Naturally, the precocious Prince Albert was a self-declared disciple of the Humboldts. ‘I have been constantly impressed while reading the first volume of your Kosmos [Cosmos: A Sketch of a Physical Description of the Universe] with my desire to thank you for the high intellectual enjoyment its study has afforded me,’ he effusively wrote to Alexander von Humboldt from Windsor Castle. (Von Humboldt unkindly dismissed the letter as ‘stiff and unmeaning’.) Above all, what Prince Albert wanted to do was translate the Humboldtian ideal of art and science, humanities and technology on to British soil as part of his broader ‘culture war’ against the landed, Anglican, self-satisfied philistinism of the British ruling class. And the profits from the 1851 Great Exhibition gave him the opportunity to do ‘The empirical sciences are never complete,’ Alexander von Humboldt wrote so: south of Kensington Palace the market gardens of Brompton would become his own Museum Island, complete with a similarly ambitious range of cultural institutions — from the Imperial Institute to the Royal Albert Hall to the ‘V&A’, and now the Science Museum as well as the Natural History Museum: ‘Albertpolis’.

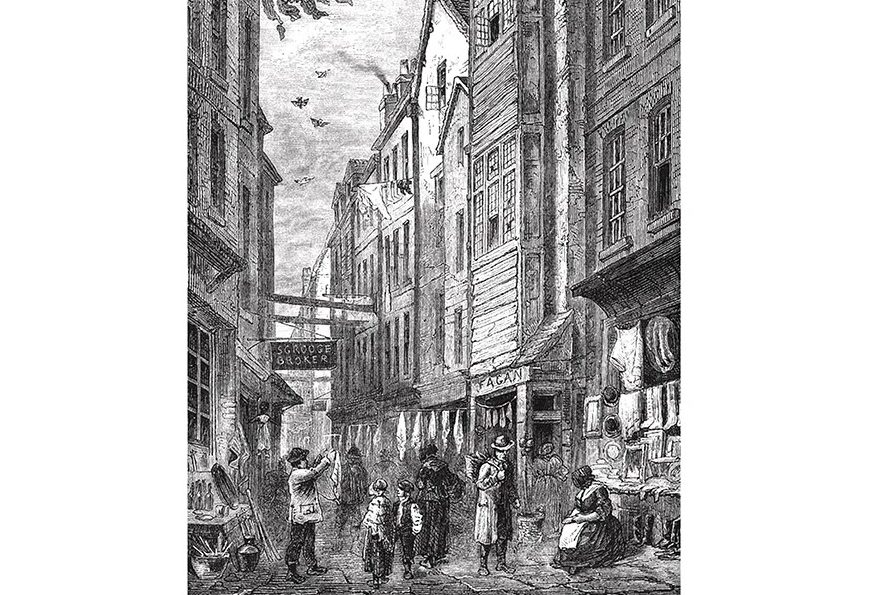

‘Education reform lay at the heart of his vision,’ explains V&A curator Julius Bryant of Albertopolis. ‘For these were not to be traditional museums as galleries for connoisseurs and archives for antiquarians, but rather places for the widest public, where collections on display would prompt instruction and debate.’ Wilhelm von Humboldt’s philosophy of democratic access and public improvement found a ready echo in the South Kensington museums’ commitment to popularizing its collections with open lectures; gas-lit galleries to encourage afterwork visits; family cafés; and object labels instead of expensive guidebooks. These People’s Galleries were to foster a broader understanding of citizenship and responsibility for self-improvement (as well as upping the quality of design).

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2021 US edition.