What remains unsaid about The Closer? In the past two weeks, countless thinkpieces have tackled the controversy around Dave Chappelle’s new special by trying to determine where its content falls on the line between funny and offensive, provocative and hateful, punching up versus punching down. Some analysis has been thoughtful; some has been shallow and reactionary. But virtually all of it centers on the question of whether Netflix should have removed or censored the special for being “harmful” to vulnerable people.

That notion is one that Netflix executive Ted Sarandos summarily rejected in a statement sent to employees, writing that “while some employees disagree, we have a strong belief that content on screen doesn’t directly translate to real-world harm.” (Sarandos has since apologized, not for asserting the lack of causal effects between comedy and violence, but for being inadequately sensitive in expressing them.)

But what if all of this, from the cultural analysis to the official response, is missing the point entirely? What if this headline-grabbing kerfuffle isn’t about the jokes at all?

The actual substance of this controversy is revealed by a list of demands, released by Netflix employees in conjunction with a walkout to protest the special. Among the demands: that Netflix “boost promotion…for trans-affirming titles on the platform” and “suggest trans-affirming content alongside and after content flagged as anti-trans”; that they “hire trans and non-binary content executives”; and, perhaps most importantly, that they “create a new fund to specifically develop trans and non-binary talent.”

Chappelle’s critics aren’t asking for censorship. They want reparations.

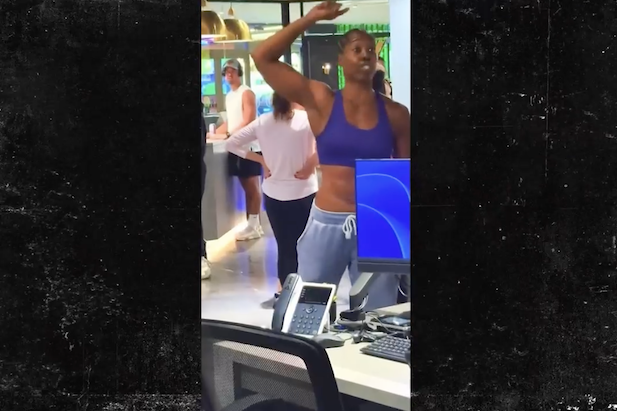

Understanding this controversy as a vehicle for material and monetary gain solves the mystery of why the protesters have doubled down so hard on claims of harm, a strategy often deployed in civil lawsuits in which aggrieved parties demand compensation for pain, suffering and trauma. The more hurt you are, the bigger your payout — and the greater the incentive to equate emotionally upsetting content with literal violence. It also explains the bizarre lack of restraint, rhetorical and otherwise, surrounding the Chappelle conversation. The Netflix walkout included a speech by Transparent creator Joey (née Jill) Soloway, claiming that “trans people are in the middle of a Holocaust”, marked by “apartheid, murder, a state of emergency, human rights crisis, there’s a mental health crisis.” Sympathetic media coverage described the controversy as a crisis for Netflix, perhaps even permanently damaging to the brand — even though the special garnered a mere 1,000 complaints despite viewership numbers upwards of ten million. A counter-protester at the walkout, who was carrying a sign that read “I LIKE JOKES”, was physically assaulted by a man who destroyed the sign and then pointed to the broken handle screaming, “He’s got a weapon!”

The whole situation seems ludicrous, but there’s an underlying logic here, one that made it just as important to destroy an anodyne banner as it was to then recast the broken handle as a weapon. The “I LIKE JOKES” sign was too perfectly absurd, a joke in and of itself: it made the protest look silly, not like the sort of serious problem that can only be solved by throwing a whole lot of money at it.

Despite the appearance that we’re in the midst of a creative boom, one in which there’s more content being produced across more platforms than ever before, getting a foot in the door isn’t easy. Getting a project funded is more difficult still. The real resentment isn’t about Chappelle’s content, but his success, particularly at a moment when a career in art or entertainment is increasingly viewed as a prize for good moral character rather than the product of excellent work. Against that backdrop, the reported $60 million Chappelle received for his Netflix specials — of which The Closer was the last and, arguably, least amusing — was bound to inspire teeth-gnashing among aspiring content creators who see this all as a zero sum game. Why him? Maybe he’s earned it, but he doesn’t deserve it. That money should go to someone good, someone noble, someone who may not be suffering for their art but who is nevertheless suffering, and should be compensated.

This isn’t a protest. It’s a PR campaign. And if Netflix caves to these demands, it’ll have been a savvy one, too.