Deeply learned and with a style all his own, Marco Grassi is as at home with Duccio as with Norton Simon; Bronzino as with Bernard Berenson; a painting on his desk as with a ‘Last Supper’ in Florence’s Basilica of Santa Croce. In the Kitchen of Art presents Grassi’s most memorable essays over a span of nearly 20 years. Beginning with a previously unpublished memoir of his Florentine upbringing, and continuing with in-depth critical discussions of the greats of Italian art along with recollections of the grandest collectors of the 20th century, this book shows the art world in the round.

Norton Simon meets Heini Thyssen

In the fall of 1973 [Norton] Simon and his second wife, the actress Jennifer Jones, were traveling in Italy and stopped to view an important exhibition of Lombard Baroque art in Milan. Aware of their presence there — only an hour from Lugano — I immediately informed my ‘boss’, Baron H.H. Thyssen-Bornemisza. The two had long competed as collectors but had never met. ‘Heini’ [Thyssen] wasted no time in arranging a dinner at the splendid Villa Favorita, even sending his gigantic Mercedes limousine to fetch his guests. As they arrived, I proudly felt at the very epicenter of the art world. After dinner, we proceeded to the adjoining series of galleries where almost 200 paintings were hung in stately array. Alas, my euphoria soon evaporated as I realized in what radically different realms the two collectors lived. Simon’s was emphatically a now world. He insisted on knowing the cost of this or that item; would its value now be less or more than when purchased?; if there were two or more works by the same master, why not sell one now?; wouldn’t restoration extract greater value? — all questions to which Heini could hardly respond and about which he became progressively more irritated. He had, after all, inherited a number of those pictures and long forgotten the prices of the rest. The evening was not a success.

2004: the Metropolitan Museum buys a Duccio

Of course, the expenditure was prodigious and this, inevitably, caught everyone’s attention. It prompted the routine exercise of comparing the values of Southampton McMansions, star pitchers or even Picassos to the object in question. Such considerations are, of course, meaningless, as are the pro forma comments about the venality of our culture (as if venality had not existed in 14th-century Siena). More to the point would be a second, careful, visit to the Met, to that first room on the right where-in a temporary dialogue of Sienese voices is in progress.

We have listened to and begun to comprehend the celestial strains of kappelmeister Duccio. Diagonally across, in a deservedly central position, is a slightly larger Crucifixion teeming with visual and emotional excitement. Also immensely rare and impeccably preserved, it is by Pietro Lorenzetti, a Sienese artist who understood his sources (Duccio, of course, and to a lesser extent, Giotto) and knew what to make of them. It tiptoed into the collection about two years ago with little fanfare (the expense was significant but not prodigious), and yet as a work of art it is almost as satisfying as its more famous neighbor. One can earnestly hope that the notoriety of the Duccio will draw more attention to the Lorenzetti; it will reward the viewer handsomely and be yet another dividend deriving from the Metropolitan’s courageous investment.

The integrity of Lorenzo Lotto

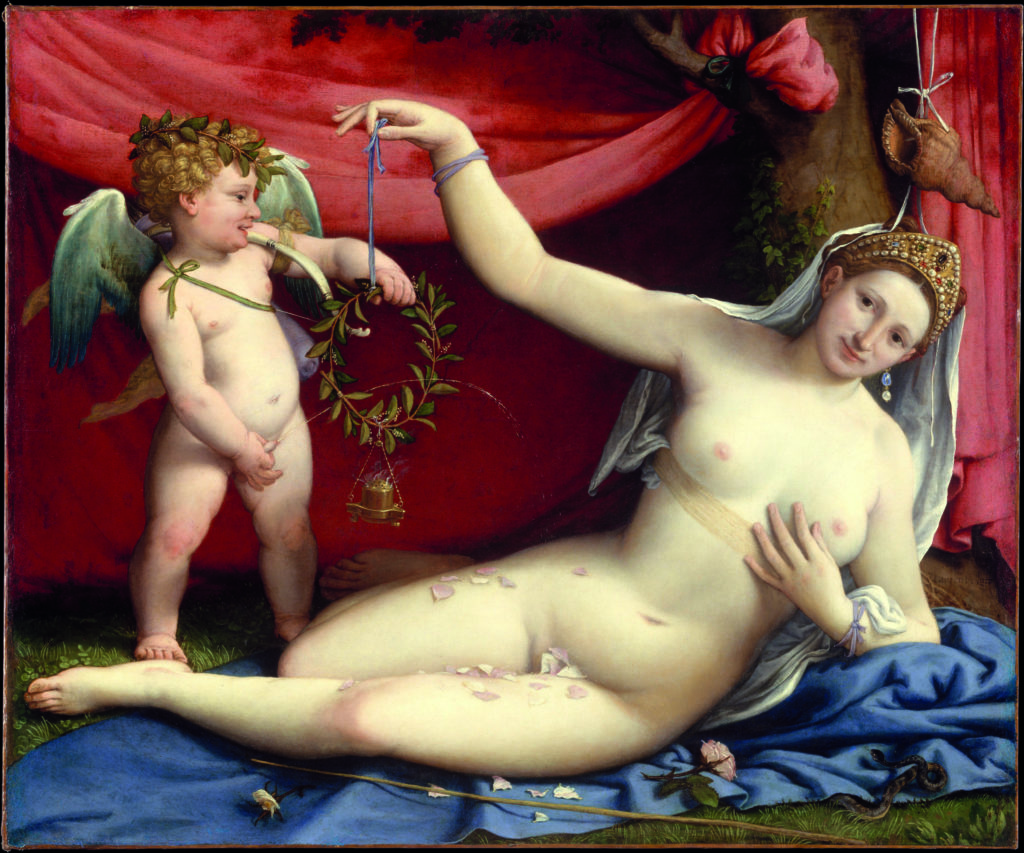

Certain artists, and not necessarily the most accomplished or significant, are occasionally accorded a privileged stature in the contemporary popular imagination. They inhabit an exalted realm of myth and romance — that places their reputation if not beyond criticism, certainly above it. Even a handful of Renaissance artists have been bestowed similar distinction (yes, Caravaggio is the obvious example). Identifying the circumstances that initiate and sustain this process of beatification is not difficult: certainly premature death (preferably suicide), a tormented sexuality or sociopathic disposition, posthumous oblivion and eventual rediscovery, extreme rarity of extant works. All these can play a part. Often, a spotty or incomplete historical record increases this aura of mystery and awe.

Lorenzo Lotto (1480-1557) fits this profile only imperfectly: the obscurity in which his reputation languished for nearly three centuries strikes a familiar note. Otherwise, he was a long-lived, exceptionally industrious, exceedingly God-fearing man, whom his contemporary Pietro Aretino famously (and with typically malicious irony) addressed as ‘Oh Lotto, good as goodness and virtuous as virtue.’ Moreover, there is copious contemporary documentation, an account book that he kept for many years, and, most importantly, an unusually large number of surviving works, many of them signed and dated.

Yet, despite this lack of mystery and drama, Lorenzo Lotto is today accorded a reverence reserved for almost no other Italian High Renaissance artist. The reason may lie in the fact that when the 20th century rediscovered this humble, provincial journey man painter, it found a man not only of boundless imaginative resources but also of unparalleled artistic and spiritual integrity, a painter who embodied all the qualities of the modern artist-as-hero: fierce independence, almost obsessive self-awareness, and a robust disdain for the fleeting rewards of this world. Thinking of van Gogh or Modigliani? Yes, but for one crucial detail: Lotto, unlike his more recent colleagues, was moved and sustained by an intensely experienced and rigorously practiced religious devotion throughout his life.

The Great Flood of Florence

On the morning of November 4, 1966 the Arno suddenly overflowed its banks and protective parapets, roaring into the city with an avalanche of mud, organic detritus and heating oil — a churning emulsion of filth. Although at the time, my family’s home was only a stone’s throw across the river from Santa Croce, I was not in Florence to witness the unfolding disaster. I learned about it on the radio as I began my workday at the Villa Favorita in Lugano, Switzerland.

For the previous two years, I had been serving there as visiting conservator for the great collection of Baron Thyssen, dividing my time with a private conservation practice I continued in Florence. The enormity of the cataclysm was progressively revealed in newscasts as I struggled to reach the stricken city by car over the next 12 hours — normally, in those days, a five-hour drive. Though by evening the flood had mostly receded, the devastation it caused in Santa Croce and other low-lying areas of the city and countryside was catastrophic. The great Franciscan basilica, its cloisters and surrounding neighborhoods had been submerged to an average depth of 18 feet. Even in areas where the flood had failed to reach such dramatic levels, the raging torrent, with its sheer force and headlong speed, left in its wake a nightmare landscape of utter chaos and destruction. Thousands of gallons of heating oil had mixed with the churning waters, everywhere revealing horribly soiled surfaces as the flood subsided.

Marco Grassi’s In the Kitchen of Art: Selected Essays & Criticism is published by Criterion Books. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2021 US edition.