I have to confess that this book sat on my desk for several months. The words “Harvard University Press” cast a strange and unsettling spell which prevented me from even opening it. Let’s be honest: academic presses are not always synonymous with rollicking reads, nor indeed are academics. They can ask an awful lot of the general reader — that would be most of us. Given how short life is, there is no good reason why reading should be more of a pain than a pleasure.

Thankfully, the spell finally wore off, which was fortunate, because this book about a book, like the book it describes, is a rare and marvelous thing. It tells the story of Wonders and Rarities, the thirteenth-century natural history, cosmography and compendium of marvels written by Zakariyya Qazwini, a Persian naturalist and judge.

“The path is tortuous and only for the brave of heart,” Travis Zadeh, a professor of religious studies at Yale, warns in his introduction, and here I admit my morale faltered. The reader must navigate “an almost impossible voyage past the Scylla of pure reason and the Charybdis of benighted superstition.” Stay with him, though. The best journeys require some effort and application. There is a material difference between the rewards and experiences of an all-inclusive week in Magaluf and a couple of months hiking in the Hindu Kush. And Zadeh promises dragons.

His writing quickly reveals him as a likable and expert guide to this challenging terrain. He quotes approvingly from Qazwini’s own introduction, in which the Persian relates how, worn out from his travels and separated from his family and homeland, he decided to settle down in Iraq and immerse himself in books on the recommendation of an unnamed poet who declared: “The best companion of all times is a book.”

Qazwini was a blue-blooded Muslim, who claimed descent from Anas ibn Malik, one of the Prophet Mohammed’s early companions, and lived through not one but two devastating, world-changing upheavals. The first came in the fiery form of Genghis Khan, whose Mongol hordes destroyed his home city of Qazvin in 1220, massacring its 40,000 inhabitants before moving on to their annihilating conquests of some of the most storied cities on Earth: Samarkand, Bukhara and Tirmith, Marv, Balkh, Herat and Ghazna, Nishapur, Rayy and Hamadan, across a swathe of Asia encompassing today’s Iran, Afghanistan and Uzbekistan.

The second shock came after Qazwini relocated, via central Asia and the Levant, to the Iraqi city of Wasit, where he was appointed a judge. Then, in 1258, Genghis Khan’s grandson Hulagu fell upon neighboring Baghdad, the Fountainhead of Scholars, burning the world-illuminating City of Peace to the ground and slaughtering its population of hundreds of thousands. Wasit followed, but Qazwini survived.

The Wonders of Creation and the Oddities of Existence, to give Qazwini’s book its full title, was a breathtaking bid to capture the entire world between its elegantly-tooled leather covers. First published c. 1262, it was dedicated to “the great and just patron and grandee” Ala al-Din Ata Malik al-Juvayni, governor of Iraq, who would earn lasting literary fame through his history of Genghis’s Mongol empire.

All the world is indeed here, united in a way which is unfamiliar to the modern rational sensibility but which was comprehensible to the medieval mind, Muslim, Christian or otherwise. Then, religion, science and magic were not poles apart. Qazwini artfully blended them into a more or less harmonious unity, laid out in a three-tier structure, starting in the heavens, then traveling down first to our sublunar Earth and down again to the animal, vegetable and mineral world.

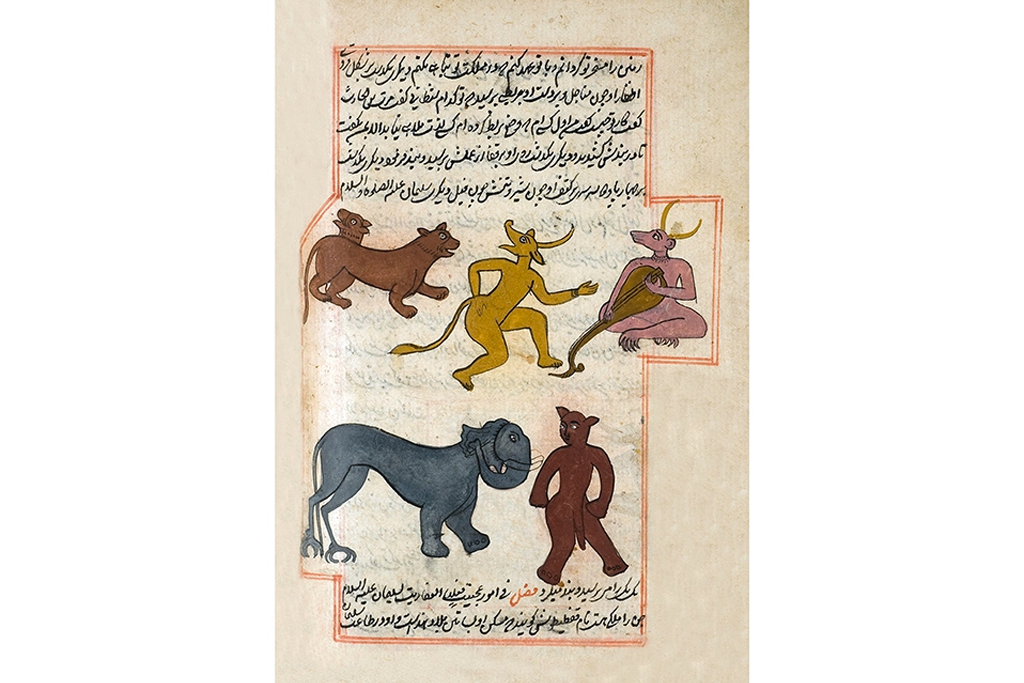

He gives us geography and geomancy, astronomy and astrology, alchemy, philosophy and metaphysics. Botany and medicine comfortably rub shoulders with mischievous jinns, talismanic powers, dog-headed men (shades of Herodotus), women who grow on trees and cattle-devouring dragons. This is no aimless celebration of the weird and wonderful. It is through contemplation of the marvels of creation, Qazwini argues, that one appreciates the existence of God the creator. Wonder is “perplexity that occurs in humans due to their lack of knowledge concerning the cause of something.” And the feelings of both wonder and perplexity themselves bring pleasure through the use of our intellect. Or something like that.

Blithely, and with no apparent contradiction, Qazwini whisks us from “sex magic” and demon possession to “pious invocations to the majestic power of God.” This is an enlightened, endlessly curious Muslim world view of a prodigiously well-read and well-connected scholar, with wonder as his — and our — constant companion. He combines ‘the authority of science with levity and awe’.

Qazwini knew some of the finest minds of his generation and was familiar with the works of many who had come before him, from Aristotle, Galen and Ibn Sina (better known in the West as Avicenna) to Razi, the greatest physician of the medieval world and scourge of medical quackery; the mathematician, physician and philosopher Nasir al-din-al-Tusi; and the devil-conjuring occultist Mohammed al-Tabasi. He personally knew the hugely influential Ibn Arabi, the saintly poet, philosopher and mystic from Murcia. The long survey of these intellectual influences and inheritances make up some of the more demanding sections of this book, but it is worth persisting.

Zadeh would be the first to acknowledge that Qazwini’s book has had a mixed afterlife. Swiftly translated from Arabic into Persian, then Urdu and Ottoman Turkish, it coursed like wildfire through the bilad Islam, or Muslim lands, entertaining and enchanting readers across several continents for centuries. In India especially the feast of storytelling proved riotously popular into the nineteenth century, with spectacular illuminated editions and exotic and erotic images galore enhancing its aesthetic and sensory appeal.

If that was all positive, the negative side of the ledger, according to Zadeh, appeared in the villainous form of western orientalists and, later, superstition-bashing Muslim reformers, starting with the seventeenth-century French scholars Barthélemy d’Herbelot and Antoine Galland, respectively the author of Oriental Library and the translator of A Thousand and One Nights. Qazwini was not alone in having his reputation trashed. The wider Muslim world would suffer too. Henceforth in the western imagination, Zadeh writes: “Islam was tyrannical and oppressive, its adherents superstitious, decadent, childish, ignorant, feminine, deviant and deceptive.”

Hang on a minute. While few will begrudge his smart kick up the orientalists’ backsides, Zadeh omits to mention the equally unflattering view many Muslims held of western infidels for many centuries. This was hardly one-way traffic. For a little more balance we might have heard, for example, from Mohammed ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, the ninth-century master mathematician, astronomer and geographer (think algebra and algorithms), who considered the Franks filthy, unhygienic and treacherous, given to savagery, sexual licentiousness and warfare. Or the tenth-century Abbasid historian Al Masudi, the “Herodotus of the Arabs,” who considered them gross in nature, harsh-mannered, dull-witted and heavy-tongued. Or the Muslim judge Said ibn Ahmed, writing from Toledo in 1068 of contemptible, pale-skinned and corpulent European barbarians, closer to beasts than humans, who lacked “keenness of understanding and clarity of intelligence and are overcome by ignorance and apathy, lack of discernment and stupidity.”

We can forgive Zadeh this oversight, which, in the wider panorama of his book, is no biggy. In his passionate and erudite mission to restore Qazwini to center stage, he has given readers a book filled with its own wonder and marvels. Like his hero, he well understands the most important thing: “What matters is a good story.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.