Passing is Rebecca Hall’s adaptation of the Nella Larsen novella (1929) about two biracial women, one of whom chooses to pass for white, and one who does not, and the effect they have on each other, and it’s superbly done. It’s tightly made, exquisite to look at, strangely tense, wholly riveting and it’s also, let’s be honest, just the right length for a film (90 minutes).

Hall — who wrote the screenplay and directs, and is otherwise an actress — is the daughter of theater director Peter Hall and opera singer Maria Ewing and you could say she has skin in the game. When she was growing up, she has said, she would sometimes look at her mother and wonder: are you a black woman? But nothing was ever said so she said nothing, only later discovering that her mother’s father had been biracial and brought up all his children as white. (“Passing” will mean different things to different people and as a Jew I sort of experience it in the form of people saying: “I can’t see it,” always intended as a compliment. You could pass!)

It’s a fascinating subject, explored here via the two women, Irene (Tessa Thompson, excellent) and Clare (Ruth Negga, excellent). They are childhood friends who lost touch but happen to bump into each other in New York’s whites-only Drayton Hotel. It’s rare for Irene to wish to pass but not Clare, whose rich, chillingly racist white husband (Alexander Skarsgard) has no idea she is anything but white. Clare tells Irene they have a daughter who can also pass but she never dared have another child as throughout her pregnancy she feared her baby would be “too dark.” “My boys are dark,” says Irene stiffly.

They are joined by Clare’s husband who, assuming Irene is also white, immediately drops the N-word while expressing his hatred for all black people. Irene laughs, as she doesn’t know where else to put her horror, while Clare looks on with what? Triumph? Shame? Excitement? Malice? It’s complicated, says this film.

Irene returns to her well-to-do home in Harlem where she lives with her dark-skinned doctor husband (André Holland) and their two young sons, and that would be that, except Clare increasingly insinuates herself into their lives and among their friends. Clare is a beauty, and Clare shimmers, and Clare is flirty and seductive, but what does she want from Irene and her family? Irene is restrained, not flashy, and says she is satisfied — “I have all I want” — but does she? Or might she envy the shimmering, exciting, flirty Clare? Is she attracted to her sexually? Might she wish for children who do not have to suffer being called the N-word on the street? There is no formal plot and little is spelled out. This relies on both lead actors conveying the interior lives of their characters — their fears, anxieties and desires — and both succeed remarkably. You won’t be able to take your eyes off either. Nor will you wish to.

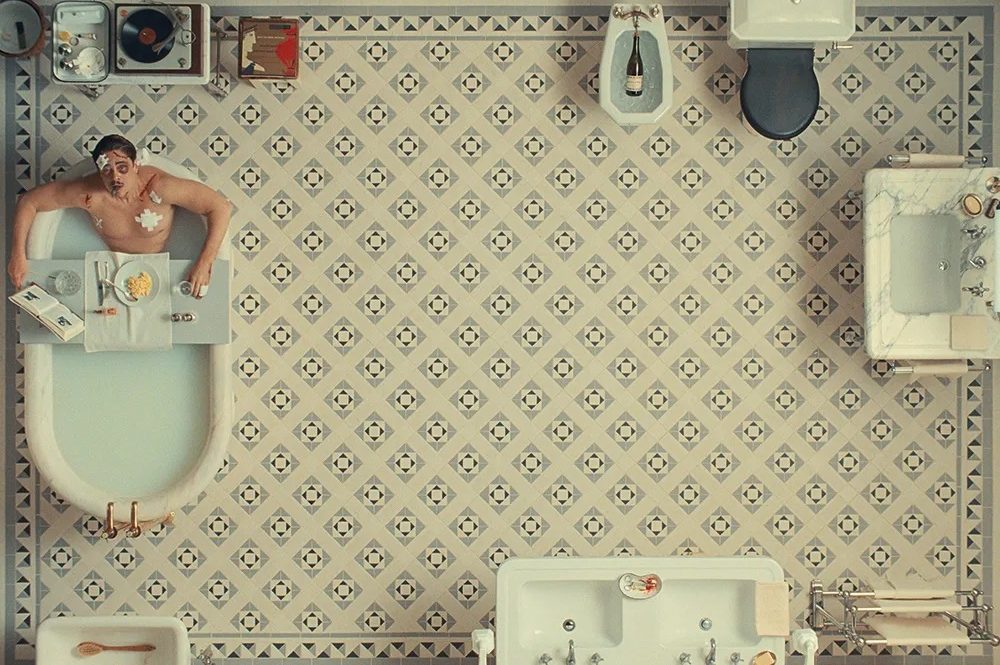

Hall has filmed in crisp black and white, which sounds like a ghastly cliché, given the circumstances, but it works terrifically well. (The first time we meet Clare she is suffused in whiteness. And also, remember, with black and white, it is mostly grays.) Plus it’s presented in the 4:3 aspect ratio, which is only 33 percent wider than it is tall (most films today are 16:9, which is 78 percent wider than tall), hence the boxed-in, claustrophobic feel. Unless you have read the novella, you won’t know where this is heading, which leads to unease throughout. You’ll sense these two women somehow can’t co-exist, as it’s too difficult, so how will it pan out? I can’t say. I can only say it’s outstanding, it’s on Netflix so you don’t have to go anywhere, and it’s just the right length.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.