We all have our favourite period of Parisian history, be it the Revolution, the Belle Époque or the swinging 1960s (the cool French version, with Jean-Paul Belmondo and Françoise Hardy). Agnès Poirier, the author of this kaleidoscopic cultural history, certainly has hers: the turbulent 1940s, which saw the French capital endure the hardships of Nazi occupation before throwing off this yoke and embracing freedom in every aspect — sexual, political and intellectual.

Leading the way was that maligned couple, Jean-Paul Sartre, the philosopher, political activist and father of existentialism, and Simone de Beauvoir, the brilliant pioneer feminist, who was his life partner, if often errant lover. Poirier lists an impressive cast of over 30 figures who contributed to the Left Bank’s predominance in this entertaining and well-written story.

Most of them are French (including Sartre’s sparring partner Albert Camus). But there are also 13 Americans, such as the novelist Nelson Algren, who became Beauvoir’s grand amour, and the artist Ellsworth Kelly; plus a solitary Briton, the flighty Sonia Brownell, who had promoted resistant writing in Horizon magazine during the war and bedded Sartre’s lieutenant, the phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty. A symbolic baton-passing occurred in 1946 when Horizon published a French issue which denounced the ‘lassitude, brain fatigue, apathy and humdrummery of English writers’ and artists, and hailed the new ‘intellectual vitality and confidence’ which ‘blazed’ across the Channel.

Poirier does not miss a trick in her lively accounts of the intense discussions and adulterous liaisons that centred on the Café de Flore or the nearby nightclub Le Tabou; but her real achievement is to contextualise these politically and culturally. When Hemingway, the first of the returning Americans, rolled into Paris in August 1944, the city had been through four years of humiliating German rule, when, along with feats of bravery, it had witnessed harrowing cases of collaboration and compromise. One example of this was when Gaston Gallimard, the head of France’s leading publishing house, appointed the fascist Pierre Drieu la Rochelle to run his influential magazine the Nouvelle revue francaise, knowing that this would enable its former editor Jean Paulham to work in an adjoining office and develop a cell of resistant writers.

But then, after a necessary purge advocated by Camus, came the ideological reckoning. As Sartre won Gallimard’s backing for a new journal Les temps modernes (named after the Charlie Chaplin film), a fierce battle developed between communists, who enjoyed the high moral ground for being the most effective resisters, and Gaullists, who had conducted their war from London. Which was better? Faced by the emerging Cold War, Sartre and his associates sought a middle way, emphasising concepts of choice and gratuitous acts of freedom in their new creed of existentialism, which the communists branded ‘a sordid and frivolous philosophy for sick people’.

Sartre even started a middle-of-the-road party, the RDR, whose desired third way in politics matched the advocacy of the third sex by polyamorists such as Dominique Aury, who later (as Pauline Réage) wrote the sado-masochistic novel Story of O, and Janet Flanner, the gimlet-eyed American journalist, who adopted the nom de plume Genet, after the homosexual writer. But a strong element of war guilt still bedevilled the collective consciousness; Sartre could not maintain his even-handedness and drifted towards communism, which seemed to command the tide of history.

One of Poirier’s anecdotes concerns Arthur Koestler’s return to Paris in October 1946. His anti-communist novel Darkness at Noon had been enjoying phenomenal success in the fevered political atmosphere of the time. One evening he and his English girlfriend, Mamaine Paget, went out with Sartre, Beauvoir and the real Jean Genet. After Mamaine departed, Koestler took Beauvoir back to her hotel, La Louisiane, and made typically violent love.

A week later he and Mamaine met Sartre and Beauvoir again in an Arab bistro, taking Camus and his long-suffering wife Francine for company. On this occasion Camus, a serial philanderer, seduced Mamaine. As the party became increasingly drunk, Sartre refused to be deterred by the dim recollection that he was giving a keynote speech to a Unesco conference the following morning. He managed this after two hours’ sleep and a liberal infusion of Orthédrine, one of several amphetamine-type substances that this generation used (with alcohol) to fuel work and play.

Shortly afterwards, Koestler found himself the butt of angry denunciations of his anti-communism, which appeared in Les temps modernes under the title ‘Le Yogi et le prolétaire’ (after his latest book The Yogi and the Commissar). To bolster his leftist credentials, Sartre sanctioned these attacks — the kind of weaselly initiative which earned him the contempt of Tony Judt, whose 1992 study Past Imperfect covers this ground more rigorously than Poirier. The magazine’s editor Merleau-Ponty had a personal grudge because he had fallen for Bronwell, who told him that Koestler was a ‘sadist’ who had forced her to abort their child after a brief affair.

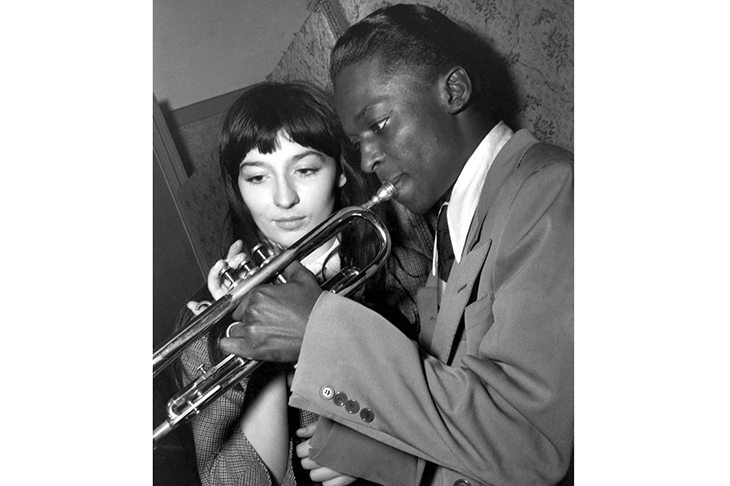

More integral to the story were the Americans who came looking for stimulus. Poirier covers this influx well, from black writers such as Richard Wright and James Baldwin, who found Paris a refuge from segregation, through to jazz musicians, including Miles Davis, who fell for the hedonistic Juliette Gréco, to more hypocritical authors like Saul Bellow, who parked his family on the bourgeois Right Bank before stealing across the river for illicit romance. The ranks of these Right Bankers were augmented from 1947 by officials and hangers-on from the Marshall Plan, which Poirier presents as a ‘good thing’, along with nascent pan-Europeanism.

Apart from occasional repetitions, such as twice referring to Flanner’s reputation for beautiful lovers, Poirier’s only failing is that her story is so star-struck. Perhaps this is inevitable in a book about the Left Bank. But the average Parisian inhabitant hardly gets a look in, and this is wrong when Poirier explores early French feminism without much emphasis on women’s position in wider society.