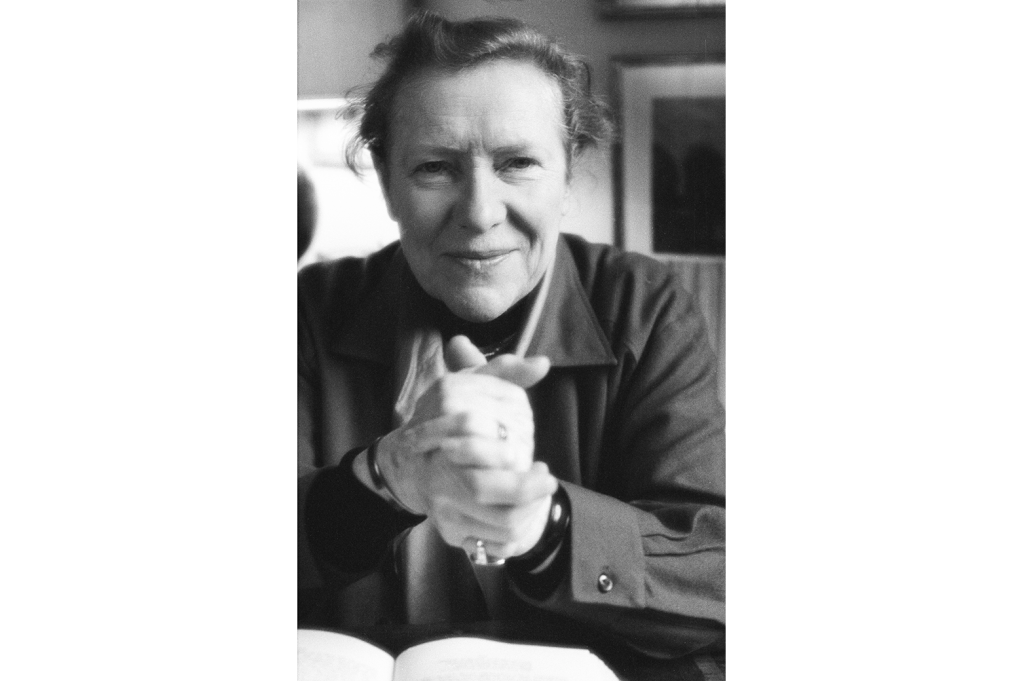

In 1975, I was commissioned to interview Sybille Bedford, by then a leading light in the literary world. She lived in a small house in Chelsea. As I got out my notebook, she said, ‘I hope you are not going to ask me about my life.’ She spoke freely about her work, though.

A Legacy, the novel she published in 1956, had become an instant classic. Evelyn Waugh had reviewed it in The Spectator with all the authority at his disposal: ‘We gratefully salute a new artist.’ In a letter to Nancy Mitford he further praised the novel: ‘What a brilliant plot!’ A Legacy was high art at a time when the Angry Young Man and the kitchen-sink style were low art or no art at all.

We found that we had friends in common. One of them was Stanley Olson, a young American writer in the Henry James mode, and he appealed to Sybille because like her he was a good cook and a connoisseur of wine. I see the two of them deep in a conversation casting doubt on the storage facilities of London’s leading wine merchants. A day came when I invited them both to the house. A friend in the trade recommended Château Verdignan. Sybille said she had never heard of it. She seemed not to mind what impression she might be making. She did not bother about her appearance either, invariably wore trousers and complained about wearing a hat. The French phrase ‘grand Bohème’ fitted her perfectly.

A slight intonation, a purr, was the only clue that she had been born in Berlin in 1911, a subject of Kaiser Wilhelm. Well known as a biographer of eminent writers, Selina Hastings does her level best to disentangle Sybille’s peculiarly complicated background. Sybille’s parents, as the second sentence of the book’s opening page states, were ‘hopelessly incompatible’. Her father, Baron Maximilian von Schoenebeck, kept himself to himself, preferring animals to people. An army officer stationed in France, he was accused by the French of espionage and sent to prison in what might have been a second Dreyfus scandal. His first wife had died, leaving a teenage daughter known as Katzi, a half-sister in due course to Sybille. Lisa, his second wife and Sybille’s mother, was Jewish, or ‘Judaeo-Agnostic’, as they qualified it. Still living in Germany in the Hitler years, Lisa’s elderly mother, Anna Bernhardt, committed suicide for fear of being deported, a fate covered here in just two lines.

The Schoenebeck house was in Feldkirch, a village close to the border with France. The village school, a few weeks in a convent and then a tutor in London was the sum total of Sybille’s education. Hastings quotes a passage from the novel Jigsaw (1989) which gives away the image that Sybille always had of herself — the interview I did with her has a more or less identical self- analysis:

‘My attachment to England was instinctive, a bid for, if not roots, a kind of self-preservation. From early on I had the absolute if shadowy conviction that I would become a writer and nothing else; I held on to the English language as the rope to save me drifting awash in the fluidities of multilingualism that surrounded me.’

For a full-time writer, her output of four novels was unexpectedly small. All of them are elaborations, sometimes dramatizations, of actual experience. In the First War, for instance, she was packed off to Berlin to live with the Herzes, in-laws of Maximilian’s through his first wife, and A Legacy is a closely remembered evocation of them; the name change of Herz to Merz is hardly anonymous. Absence of invention leaves the four novels closer to autobiography than to fiction. Perhaps she should have stuck to belles-lettres like her first published book, A Visit to Don Otavio (1953), a kind of conceit in a farfetched Mexican setting of set-pieces, character sketches, lampoons, much comedy and plain reportage which altogether could hold its own against A.W. Kinglake or Edward Lear.

In 1925 Lisa married Nori Marchesani, and the following year they took Sybille with them and settled at Sanary-sur-Mer, a fishing port halfway between Toulon and Marseilles. Picturesque, Sanary between the wars was for intellectuals what Biarritz was for the beau monde. Clever but unfulfilled, Lisa was prone to moods of depression mixed with raw anger. When Nori fell in love with another woman, Lisa went to pieces, in turn an alcoholic and a drug addict. She too attempted suicide and died in a Berlin hospital in 1937, in time to avoid being deported and murdered in an extermination camp. It speaks in favor of Sybille that she did everything she could to help this doomed mother. ‘Here was my home, here I was going to live,’ goes another quotation from Jigsaw, ‘here, the gods willing, I was going to write my books.’ She wrote nothing. ‘So much siesta and dining out and never any work,’according to an entry in her diary. The rise of Hitler brought German refugees to Sanary: Thomas Mann and his family; Lion Feuchtwanger, the author of Jew Süss and a communist received by Stalin in Moscow; Stefan Zweig, Kisling the painter, and Bertolt Brecht.

The English contingent at Sanary were stars in the literary Homintern of the day, including Eddy Sackville-West, Eddy Gathorne-Hardy, Raymond Mortimer, Jimmy Stern and Brian Howard. At midnight in a bar with ambisexual dancing, someone made an offensive remark about Brian Howard’s boyfriend, and within seconds a general fracas had broken out. Described in Sybille’s memoir Quicksands (2005), this incident is a good example of how literally her fiction reproduced her experience. In a letter to his mother, Brian Howard wrote ‘Sybille turns out to be an angel.’ He continued, deceiving himself, ‘I really think I can get a bit of writing done.’ Sybille might well have finished life as another disappointed Brian Howard had Aldous and Maria Huxley not taken her up in Sanary. Huxley was then famous. His novels set aesthetic standards for the Twenties. Brave New World came out in 1931. That summer, Cyril Connolly and his wife Jean rented a house at Sanary. Evelyn Waugh stayed with them and wrote in a thank-you letter: ‘it was exciting meeting the Huxleys’. Cyril’s admiration soon curdled, and he absolved himself in his diary, ‘The Huxleys have added ten years to my life.’

Hastings writes that Sybille had looked on Maria Huxley as someone she could depend on and admire. The two of them became lovers, ‘a sexual bonding that was to continue intermittently for a number of years’. For the sake of symmetry, so to speak, Aldous seduced Lisa and put an unkind but recognizable portrait of her into his 1936 novel, Eyeless in Gaza.

As war approached, the Huxleys were instrumental in changing Sybille’s nationality from German to British. ‘We must get one of our bugger friends to marry Sybille,’ said Maria. Marriage to an Englishman was the prerequisite. Walter Bedford, an attendant at a gentleman’s club, was prepared to go through with the charade. Once the day of the civil wedding was over, Sybille never again met the man whose name she carried for the rest of her life. Repaying Aldous Huxley, she was to spend five or six years writing his authorized biography ‘[a]s though one were sitting at the feet of a large and benign cat’. She virtually canonized him, failing to mention anything discreditable, notably his growing irrationality and the affair he had had with her own mother.

As France was falling in 1940, Europeans of all sorts managed to flee to the United States and Sybille was one of them, a cosmopolitan among other cosmopolitans. From the literary point of view, the seven years she spent in America were unproductive, but a letter from Annie Davis is a portent of what is to come: ‘I could never have enough of you, in bed and out of bed.’ At best, only a few academics will know that Annie Davis came from Baltimore and was Cyril Connolly’s onetime sister-in-law. Eventually back in Europe, Sybille settled in Rome with interludes in France and Switzerland.

From then on, the whole tenor of this biography changes, turning into a Lesbian Gazette. A specimen extract goes like this:

‘Relations with Allanah, however, were far from easy, she and Sybille angrily snapping and constantly on each other’s nerves, while Allanah “was so beastly to Eda, so resisting the fact of her presence that it had me isolated from her and sad, and cross too”. Allanah’s bad temper stemmed partly from the awkward fact that in the past she and Eda had themselves been lovers, and also from her current unhappiness over the end of her affair with Fay Blacket Gill; Fay had recently fallen for Patricia Laffan, the actress with whom Sybille had enjoyed a brief interlude while in Rome. Allanah was miserable over the rupture, and it was not until the beginning of the following year that she regained her good humor, happy with a new lover, Charlotte (“Charley”) Delmas.’

Among the archives with the necessary documentation is the Humanities Research Center of the University of Texas. The repetition of it, the preoccupation, stretches Hastings’s language. She overuses adjectives like ‘slender’ and ransacks the lexicon for fresh words and phrases to bring alive various affairs, liaisons, relationships with or without the adjective ‘passionate’: ‘intimate friendship’, ‘the Lord Byron of the Ladies’, the ‘three fatal words’ (a euphemism for ‘I love you’), ‘sexual carousel’ and so on. ‘Sybille found herself deeply enamored’ is one of the odder constructions. Love in Sybille’s carryon appears to have been synonymous with desire and had nothing to do with trust, obligation or sacrifice.

Someone who believes that the purpose of biography is to give the facts pure and simple will find that this book does the job very well. But someone who thinks that the purpose of biography is to examine a life and pass judgement on it will be left hanging in the air. In one perspective Hastings presents Sybille as a great writer making a success of it in very unfavorable circumstances, but in another perspective Sybille is a poor unhappy woman who squandered her talents time and again, and often complains to friends that she is going through ‘a very difficult time of self-hatred, ineffectualness, lovelessness, misery and guilt’. The absence of anything judgmental takes away the weight the book would otherwise have.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2021 US edition.