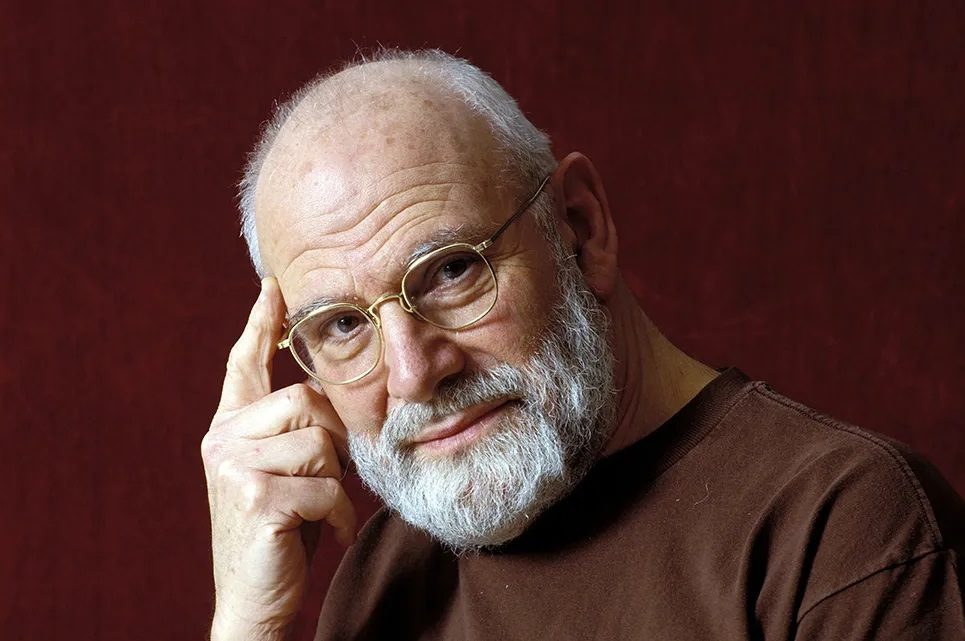

Oliver Sacks, who died in 2015, first came to public attention with his descriptions of fascinating neurological conditions in accessible articles and books. He was one of the first doctors to attempt to break down the barriers between the medical profession and the layman by eschewing esoteric jargon and explaining complex brain pathology simply while never losing sight of the patient as a human being.

He exuded compassion and honesty. He brought attention to little-known illnesses such as encephalitis lethargica, or sleeping sickness, of which there was an epidemic after World War One. In his book Awakenings (1973), he wrote about how these patients were locked into a syndrome similar to severe Parkinson’s; how they responded, almost miraculously, to the drug L-dopa; and how, tragically, they then stopped responding to it.

He showed similar sympathy for sufferers from Tourette’s, deafness, autism, genetic color blindness, migraines and many other little-understood conditions. His holistic outlook was exemplified by his investigations into the effects of the arts — especially music — on the brain. But his interests were not confined to neurology. He also published articles on plants, worms and cephalopods. Outside of work, he was a motorcycle enthusiast, a weightlifter and an enthusiastic imbiber of recreational drugs. He was also an ardent letter writer.

In Letters, Sacks’s longtime friend and editor Kate Edgar has gathered together hundreds of the letters he wrote to family, friends, readers, patients and fans during the decades he lived in America. He moved there after studying medicine at Oxford and doing house jobs at the Middlesex in London — his ostensible reasons being to explore the country and progress in medicine away from the stultifying, conservative structure in the UK. Although not yet out, he was gay.

Another factor seems to have been similar to the reason his schizophrenic older brother moved to Australia. Michael’s psychotic breakdowns became intolerable, even though Sacks’s parents (both doctors) were warm and supportive and the extended family were close. Schizophrenia would remain an interest of Sacks. He was deeply impressed when he visited the Belgian town of Geel, where the whole community acted as carers for the severely mentally ill.

The letters reveal his curiosity, his concern for others and his analytical mind; they provide an insight into the way his cerebral neurons would fire off and stimulate neighboring ones, setting him scurrying about like a puppy, following various trains of thought. He always had a project on the go: for him investigation, and then describing his findings, was a form of self-fulfillment.

Early letters to his parents show his dissatisfaction with the way junior doctors were used as cheap labor without involving them in the care of patients. There is a shocking account of how one of his bosses became jealous of his research and tried to plagiarize it; and there are wistful reminiscences about medical colleagues ignoring his books. We read of his deep depressions leavened by spells of hypomania — and his worry that he might share Michael’s susceptibility to mental illness. But it turns out that these are simply his responses to life’s vicissitudes. As he found his niche as a writer, and received critical acclaim, he became much happier in his skin.

What is evident from these letters is that his compassion brought him enormous love both from friends and patients. He knew many people accomplished in a variety of fields, including physics, chemistry, anthropology and psychotherapy, as well as pop singers, writers and other high achievers. But his letters to teenage readers are as warm as those to his closest friends. Even his replies to cranks are measured. While clearly stating his lack of belief in shamanism, clairvoyance and other forms of woo, he is never gratuitously rude.

His personal journey is also something to savor. The youth who resents his loving parents for sending him away from war-torn London, and who borrows thousands of pounds from a family friend which he fails to repay for years, grows into a generous-hearted man who always has time for others and who constantly invites people to stay. These letters provide a wonderful portrait of a truly exceptional individual.